Previous set of notes: Notes 3. Next set of notes: Notes 5.

In the previous set of notes we saw that functions that were holomorphic on an open set

enjoyed a large number of useful properties, particularly if the domain

was simply connected. In many situations, though, we need to consider functions

that are only holomorphic (or even well-defined) on most of a domain

, thus they are actually functions

outside of some small singular set

inside

. (In this set of notes we only consider interior singularities; one can also discuss singular behaviour at the boundary of

, but this is a whole separate topic and will not be pursued here.) Since we have only defined the notion of holomorphicity on open sets, we will require the singular sets

to be closed, so that the domain

on which

remains holomorphic is still open. A typical class of examples are the functions of the form

that were already encountered in the Cauchy integral formula; if

is holomorphic and

, such a function would be holomorphic save for a singularity at

. Another basic class of examples are the rational functions

, which are holomorphic outside of the zeroes of the denominator

.

Singularities come in varying levels of “badness” in complex analysis. The least harmful type of singularity is the removable singularity – a point which is an isolated singularity (i.e., an isolated point of the singular set

) where the function

is undefined, but for which one can extend the function across the singularity in such a fashion that the function becomes holomorphic in a neighbourhood of the singularity. A typical example is that of the complex sinc function

, which has a removable singularity at the origin

, which can be removed by declaring the sinc function to equal

at

. The detection of isolated removable singularities can be accomplished by Riemann’s theorem on removable singularities (Exercise 37 from Notes 3): if a holomorphic function

is bounded near an isolated singularity

, then the singularity at

may be removed.

After removable singularities, the mildest form of singularity one can encounter is that of a pole – an isolated singularity such that

can be factored as

for some

(known as the order of the pole), where

has a removable singularity at

(and is non-zero at

once the singularity is removed). Such functions have already made a frequent appearance in previous notes, particularly the case of simple poles when

. The behaviour near

of function

with a pole of order

is well understood: for instance,

goes to infinity as

approaches

(at a rate comparable to

). These singularities are not, strictly speaking, removable; but if one compactifies the range

of the holomorphic function

to a slightly larger space

known as the Riemann sphere, then the singularity can be removed. In particular, functions

which only have isolated singularities that are either poles or removable can be extended to holomorphic functions

to the Riemann sphere. Such functions are known as meromorphic functions, and are nearly as well-behaved as holomorphic functions in many ways. In fact, in one key respect, the family of meromorphic functions is better: the meromorphic functions on

turn out to form a field, in particular the quotient of two meromorphic functions is again meromorphic (if the denominator is not identically zero).

Unfortunately, there are isolated singularities that are neither removable or poles, and are known as essential singularities. A typical example is the function , which turns out to have an essential singularity at

. The behaviour of such essential singularities is quite wild; we will show here the Casorati-Weierstrass theorem, which shows that the image of

near the essential singularity is dense in the complex plane, as well as the more difficult great Picard theorem which asserts that in fact the image can omit at most one point in the complex plane. Nevertheless, around any isolated singularity (even the essential ones)

, it is possible to expand

as a variant of a Taylor series known as a Laurent series

. The

coefficient

of this series is particularly important for contour integration purposes, and is known as the residue of

at the isolated singularity

. These residues play a central role in a common generalisation of Cauchy’s theorem and the Cauchy integral formula known as the residue theorem, which is a particularly useful tool for computing (or at least transforming) contour integrals of meromorphic functions, and has proven to be a particularly popular technique to use in analytic number theory. Within complex analysis, one important consequence of the residue theorem is the argument principle, which gives a topological (and analytical) way to control the zeroes and poles of a meromorphic function.

Finally, there are the non-isolated singularities. Little can be said about these singularities in general (for instance, the residue theorem does not directly apply in the presence of such singularities), but certain types of non-isolated singularities are still relatively easy to understand. One particularly common example of such non-isolated singularity arises when trying to invert a non-injective function, such as the complex exponential or a power function

, leading to branches of multivalued functions such as the complex logarithm

or the

root function

respectively. Such branches will typically have a non-isolated singularity along a branch cut; this branch cut can be moved around the complex domain by switching from one branch to another, but usually cannot be eliminated entirely, unless one is willing to lift up the domain

to a more general type of domain known as a Riemann surface. As such, one can view branch cuts as being an “artificial” form of singularity, being an artefact of a choice of local coordinates of a Riemann surface, rather than reflecting any intrinsic singularity of the function itself. The further study of Riemann surfaces is an important topic in complex analysis (as well as the related fields of complex geometry and algebraic geometry), but this topic will be postponed to the next course in this sequence.

— 1. Laurent series —

Suppose we are given a holomorphic function and a point

in

. For a sufficiently small radius

, the circle

and its interior both lie in

, and the Cauchy integral formula tells us that

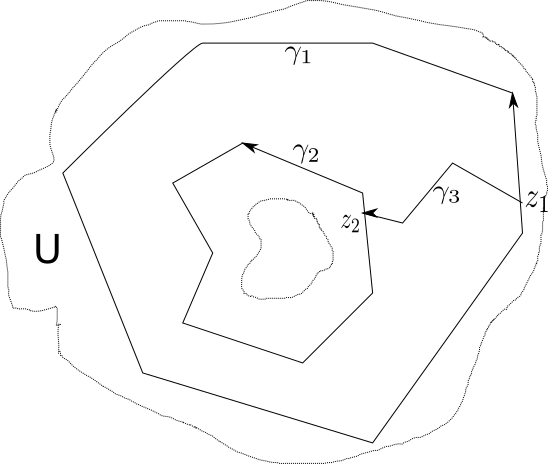

Lemma 1 (Cauchy integral formula decomposition in annular regions) Letbe a holomorphic function. Let

,

be simple closed anticlockwise curves in

such that

is contained in the interior

of

(or equivalently, by Exercise 51 of Notes 3, that

is contained in the exterior

of

). Suppose also that the “annular region”

is contained in

. Then there exists a decomposition

on

, where

is holomorphic on the union of

and the interior of

, and

is holomorphic on the union of

and the exterior of

, with

as

. Furthermore, this decomposition is unique.

In addition, we have the Cauchy integral type formulae

for

in the interior of

, and

for

in the exterior of

. In particular, we have

for

in

.

Proof: We begin with uniqueness. Suppose we have two decompositions

Now for existence. Suppose that we can establish the identity (1) for in

. Then we can define

on

by

Thus it remains to establish (1). This follows from the homology form of the Cauchy integral formula (Exercise 15(v) of Notes 3), but we can also avoid explicit use of homology by the following “keyhole contour” argument. For , we have from the definition of winding number that

By perturbing using Cauchy’s theorem we may assume that these curves are simple closed polygonal paths (if one wishes, one can also restrict the edges to be horizontal and vertical, although this is not strictly necessary for the argument). By connecting a point in

to a point in

by a polygonal path in the interior of

, and removing loops, self-intersections, or excursions into the interior (or image) of

, we can find a simple polygonal path

from a point

in

to a point

in

that lies entirely in

except at the endpoints. By rearranging

and

we may assume that

is the initial and terminal point of

, and

is the initial and terminal point of

. Then the closed polygonal path

has vanishing winding number in the interior of

or exterior of

, thus

contains all the points where the winding number is non-zero. This path is not simple, but we can approximate it to arbitrary accuracy

by a simple closed polygonal path

by shifting the simple polygonal paths

and

slightly; for

small enough, the interior of

will then lie in

. Applying Cauchy’s theorem (Theorem 54 of Notes 3) we conclude that

Exercise 2 Letbe a simple closed anticlockwise curve, and let

be simple closed anticlockwise curves in the interior

of

whose images are disjoint, and such that the interiors

are also disjoint. Let

be an open set containing

and the region

Let

be holomorphic. Show that for any

, one has

(Hint: induct on

using Lemma 1.)

Exercise 3 (Painlevé’s theorem on removable singularities) Letbe an open subset of

. Let

be a compact subset of

which has zero length in the following sense: for any

, one can cover

by a countable number of disks

such that

. Let

be a bounded holomorphic function. Show that the singularities in

are removable in the sense that there is an extension

of

to

which remains holomorphic. (Hint: one can work locally in some disk in

that contains a portion of

. Cover this portion by a finite number of small disks, group them into connected components, use the previous exercise, and take an appropriate limit.) Note that this result generalises Riemann’s theorem on removable singularities, see Exercise 37 from Notes 3. The situation when

has positive length is considerably more subtle, and leads to the theory of analytic capacity, which we will not discuss further here.

Exercise 4 (Variant of mean value theorem) Letbe a holomorphic function on an open subset

of

, and let

be a simple closed contour in

, whose interior is also contained in

. Show that for any

in the interior of

, there exists

in the image of

such that

(Hint: use the Riemann singularity removal theorem and the maximum principle.)

Now suppose that is holomorphic for some annulus of the form

Exercise 5 (Fourier inversion formula) Letbe holomorphic on some open set

that contains an annulus of the form (3), and let

be the coefficients of the Laurent expansion (4) in this annulus. Show that the coefficients

are uniquely determined by

and

, and are given by the formula

for all integers

, whenever

is a simple closed curve in the annulus with

. Also establish the bounds

and

The following modification of the above exercise may help explain the terminology “Fourier inversion formula”.

Exercise 6 (Fourier inversion formula, again) Let.

- (i) Show that if

is holomorphic on the annulus

, then we have the Fourier expansion

for all

, where the Fourier coefficients

are given by the formula

Furthermore, show that the Fourier series in (7) is absolutely convergent, and the coefficients

obey the asymptotic bounds (5), (6).

- (ii) Conversely, if

are complex numbers obeying the asymptotic bounds (5), (6), show that there exists a function

holomorphic on the annulus

obeying the Fourier expansion (7) and the inversion formula (8).

The Laurent series for a given function can vary as one varies the annulus. Consider for instance the function . In the annulus

, the Laurent expansion coincides with the Taylor expansion:

Exercise 7 Find the Laurent expansions for the functionin the regions

,

, and

. (Hint: use partial fractions.)

We can use Laurent series to analyse an isolated singularity. Suppose that is holomorphic on a punctured disk

. By the above discussion, we have a Laurent series expansion (4) in this punctured disk. If the singularity is removable, then the Laurent series must coincide with the Taylor series (by the uniqueness component of Exercise 5), so in partcular

for all negative

; conversely, if

vanishes for all negative

, then the Laurent series matches up with a convergent Taylor series and so the singularity is removable. We then adopt the following classification:

- (i)

has a removable singularity at

if one has

for all negative

. If furthermore there is an

such that

and

for

, we say that

has a zero of order

at

(after removing the singularity). Zeroes of order

are known as simple zeroes, zeroes of order

are known as double zeroes, and so forth.

- (ii)

has a pole of order

at

for some

if one has

, and

for all

. Poles of order

are known as simple poles, poles of order

are double poles, and so forth.

- (iii)

has an essential singularity if

for infinitely many negative

.

It is clear that any holomorphic function will be of exactly one of the above three categories, unless it is identically zero. Also, from the uniqueness of Laurent series, shrinking

does not affect which of the three categories

will lie in (or what order of pole

will have, in the second category). Thus, we can classify any isolated singularity

of a holomorphic function

with singularities as being either removable, a pole of some finite order, or an essential singularity by restricting

to a small punctured disk

and inspecting the Laurent coefficients

for negative

.

Example 8 The functionhas a Laurent expansion

and thus has an essential singularity at

.

It is clear from the definition (and the holomorphicity of Taylor series) that (as discussed in the introduction), a holomorphic function has a pole of order

at an isolated singularity

if and only if it is of the form

for some holomorphic

with

. Similarly, a holomorphic function would have a zero of order

at

if and only if

for some

with

.

We can now define a class of functions that only have “nice” singularities:

Definition 9 (Meromorphic functions) Letbe an open subset of

. A function

defined on

outside of a closed singular set

is said to be meromorphic on

if

- (i)

is closed in

and discrete (i.e., all points in

are isolated);

- (ii)

is holomorphic on

; and

- (iii) Every

is either a removable singularity or a pole of finite order.

Two meromorphic functions ,

are said to be equivalent if they agree on their common domain of definition

. It is easy to see that this is an equivalence relation. It is common to identify meromorphic functions up to equivalence, similarly to how in measure theory it is common to identify functions which agree almost everywhere.

Exercise 10 (Meromorphic functions form a field) Letdenote the space of meromorphic functions on a connected open set

, up to equivalence. Show that

is a field (with the obvious field operations). What happens if

is not connected?

Exercise 11 (Order is a valuation) Letbe an open connected set. If

is a meromorphic function, and

, define the order

of

at

as follows:

Establish the following facts:

- (a) If

has a removable singularity at

, and has a zero of order

at

once the singularity is removed, then

.

- (b) If

is holomorphic at

, and has a zero of order

at

, then

.

- (c) If

has a pole of order

at

, then

.

- (d) If

is identically zero, then

.

In the language of abstract algebra, the above facts are asserting that

- (i) If

and

are equivalent meromorphic functions, then

for all

. In particular, one can meaningfully define the order of an element of

at any point

in

, where

is as in the preceding exercise.

- (ii) If

and

, show that

. If

is not zero, show that

.

- (iii) If

and

, show that

. Furthermore, show if

, then the above inequality is in fact an equality.

is a valuation on the field

.

The behaviour of a holomorphic function near an isolated singularity depends on the type of singularity.

Theorem 12 Letbe holomorphic on an open set

outside of a closed singular set

, and let

be an isolated singularity in

.

- (i) If

is a removable singularity of

, then

converges to a finite limit as

.

- (ii) If

is a pole of

, then

as

.

- (iii) (Casorati-Weierstrass theorem) If

is an essential singularity of

, then every point

of

is a limit point of

as

, that is to say there exists a sequence

converging to

such that

converges to

(where we adopt the convention that

converges to

if

converges to

).

Proof: Part (i) is obvious. Part (ii) is immediate from the factorisation and noting that

converges to the non-zero value

as

. The

case of (iii) follows from Riemann’s theorem on removable singularities (Exercise 37 from Notes 3). Now suppose

is finite. If (iii) failed, then there exist

such that

avoids the disk

on the domain

. In particular, the function

is bounded and holomorphic on

, and thus extends holomorphically to

by Riemann’s theorem. This function cannot vanish identically, so we must have

on

for some

and some holomorphic

that does not vanish at

. Rearranging this as

, we see that

has a pole or removable singularity at

, a contradiction.

In Theorem 57 below we will establish a significant strengthening of the Casorati-Weierstrass theorem known as the Great Picard Theorem.

Exercise 13 Letbe holomorphic in

outside of a discrete set

of singularities. Let

. Show that the radius of convergence of the Taylor series of

around

is equal to the distance from

to the nearest non-removable singularity in

, or

if no such non-removable singularity exists. (This fact provides a neat way to understand the rate of growth of a sequence

: form its generating function

, locate the singularities of that function, and find out how close they get to the origin. This is a simple example of the methods of analytic combinatorics in action.)

A curious feature of the singularities in complex analysis is that the order of singularity is “quantised”: one can have a pole of order ,

, or

(for instance), but not a pole of order

or

. This quantisation can be exploited: if for instance one somehow knows that the order of the pole is less than

for some integer

and real number

, then the singularity must be removable or a pole of order at most

. The following exercise formalises this assertion:

Exercise 14 Letbe holomorphic on a disk

except for a singularity at

. Let

be an integer, and suppose that there exist

,

such that one has the upper bound

for all

. Show that the singularity of

at

is either removable, or a pole of order at most

(the latter option is only possible for

positive, of course). (Hint: use Exercise 5 and a limiting argument to evaluate the Laurent coefficients

for

.) In particular, if one has

for all

, then the singularity is removable.

As mentioned in the introduction, the theory of meromorphic functions becomes cleaner if one replaces the complex plane with the Riemann sphere. This sphere is a model example of a Riemann surface, and we will now digress to briefly introduce this more general concept (though we will not develop the general theory of Riemann surfaces in any depth here). To motivate the definition, let us first recall from differential geometry the notion of a smooth

-dimensional manifold

(over the reals).

Definition 15 (Smooth manifold) Let, and let

be a topological space. An (

-dimensional real) atlas for

is an open cover

of

together with a family of homeomorphisms

(known as coordinate charts) from each

to an open subset

of

. Furthermore, the atlas is said to be smooth if for any

, the transition map

, which maps one open subset of

to another, is required to be smooth (i.e., infinitely differentiable). A map

from one topological space

(equipped with a smooth atlas of coordinate charts

for

) to another

(equipped with a smooth atlas of coordinate charts

for some

) is said to be smooth if it is continuous, for any

and

, the maps

are smooth; if

is invertible and

and

are both smooth, we say that

is a diffeomorphism, and that

and

are diffeomorphic. Two smooth atlases on

are said to be equivalent if the identity map from

(equipped with one of the two atlases) to

(equipped with the other atlas) is a diffeomorphism; this is easily seen to be an equivalence relation, and an equivalence class of such atlases is called a smooth structure on

. A smooth

-dimensional real manifold is a Hausdorff topological space

equipped with a smooth structure. (In some texts the mild additional condition of second countability on

is also imposed.) A map

between two smooth manifolds is said to be smooth, if the map

from

(equipped with one of the atlases in the smooth structure on

) to

(equipped with one of the atlases in the smooth structure on

) is smooth; it is easy to see that this definition is independent of the choices of atlas. We may similarly define the notion of a diffeomorphism between two smooth manifolds.

This definition may seem excessively complicated, but it captures the modern geometric philosophy that one should strive as much as possible to work with objects that are coordinate-independent in that they do not depend on which atlas of coordinate charts one picks within the equivalence class of the given smooth structure in order to perform computations or to define foundational concepts. One can also define smooth manifolds more abstractly, without explicit reference to atlases, by working instead with the structure sheaf of the rings of smooth real-valued functions on open subsets

of the manifold

, but we will not need to do so here.

Example 16 A simple example of a smooth-dimensional manifold is the unit circle

; there are many equivalent atlases one could place on this circle to define the smooth structure, but one example would be the atlas consisting of the two charts

,

, defined by setting

,

,

,

,

for

, and

for

. Another smooth manifold, which turns out to be diffeomorphic to the unit circle

, is the one-point compactification

of the real numbers, with the two charts

,

defined by setting

,

,

,

to be the identity map, and

defined by setting

for

and

.

Exercise 17 Verify that the unit circleis indeed diffeomorphic to the one-point compactification

.

A Riemann surface is defined similarly to a smooth manifold, except that the dimension is restricted to be one, the reals

are replaced with the complex numbers, and the requirement of smoothness is replaced with holomorphicity (thus Riemann surfaces are to the complex numbers as smooth curves are to the real numbers). More precisely:

Definition 18 (Riemann surface) Letbe a Hausdorff topological space. A holomorphic atlas on

is an open cover

of

together with a family of homeomorphisms

(known as coordinate charts) from each

to an open subset

of

, such that, for any

, the transition map

, which maps one open subset of

to another, is required to be holomorphic. A map

from one space

(equipped with coordinate charts

for

) to another

(equipped with coordinate charts

for some

) is said to be holomorphic if it is continuous and, for any

and

, the maps

are holomorphic; if

is invertible and

and

are both holomorphic, we say that

is a complex diffeomorphism, and that

and

are complex diffeomorphic. Two holomorphic atlases on

are said to be equivalent if the identity map from

(equipped with one of the atlases) to

(equipped with the other atlas) is a complex diffeomorphism; this is easily seem to be an equivalence relation, and we refer to such an equivalence class as a (one-dimensional) complex structure on

. A Riemann surface is a Hausdorff topological space

, equipped with a one-dimensional complex structure. (Again, in some texts the hypothesis of second countability is imposed. This makes little difference in practice, as most Riemann surfaces one actually encounters will be second countable.)

By considering dimensions greater than one, one can arrive at the more general notion of a complex manifold, the study of which is the focus of complex geometry (and also plays a central role in the closely related fields of several complex variables and complex algebraic geometry). However, we will not need to deal with higher-dimensional complex manifolds in this course. The notion of a Riemann surface should not be confused with that of a Riemannian manifold, which is the topic of study of Riemannian geometry rather than complex geometry.

Clearly any open subset of the complex numbers

is a Riemann surface, in which one can use the atlas that only consists of one “tautological” chart, the identity map

. More generally, any open subset of a Riemann surface is again a Riemann surface. If

are open subsets of the complex numbers, and

is a map, then by unpacking all the definitions we see that

is holomorphic in the sense of Definition 18 if and only if it is holomorphic in the usual sense.

Now we come to the Riemann sphere , which is to the complex numbers as

is to the real numbers. As a set, this is the complex numbers

with one additional point (the point at infinity)

attached. Topologically, this is the one-point compactification of the complex numbers

: the open sets of

are either subsets of

that were already open, or complements

of compact subsets

of

. As a Riemann surface, the complex structure can be described by the atlas of coordinate charts

,

, where

,

,

,

is the identity map, and

equals

for

with

. It is not difficult to verify that this is indeed a Riemann surface (basically because the map

is holomorphic on

). One can identify the Riemann sphere with a geometric sphere, and specifically the sphere

, through the device of stereographic projection through the north pole

, identifying a point

in

with the point

on

collinear with that point, and the point at infinity

identified with the north pole

. This geometric perspective is especially helpful when thinking about Möbius transformations, as is for instance exemplified by this excellent video. (We may cover Möbius transformations in a subsequent set of notes.)

By unpacking the definitions, we can now work out what it means for a function to be holomorphic to or from the Riemann sphere. For instance, if is a map from an open subset

of

to the Riemann sphere

, then

is holomorphic if and only if

- (i)

is continuous;

- (ii)

is holomorphic on the set

(which is open thanks to (i)); and

- (iii)

is holomorphic on the set

(which is open thanks to (i)), where we adopt the convention

.

Similarly, if a function is a map from an open subset

of the Riemann sphere

to the Riemann sphere, then

is holomorphic if and only if

- (i)

is holomorphic on

; and

- (ii)

is holomorphic on

, where we adopt the convention

.

We can then identify meromorphic functions with holomorphic functions on the Riemann sphere:

Exercise 19 Letbe open connected, let

be a closed discrete subset of

, and let

be a function. Show that the following are equivalent:

Furthermore, if (ii) holds, show that

- (i)

is meromorphic on

.

- (ii)

is the restriction of a holomorphic function

to the Riemann sphere, that is not identically equal to

.

is uniquely determined by

, and is unaffected if one replaces

with an equivalent meromorphic function.

Among other things, this exercise implies that the composition of two meromorphic functions is again meromorphic (outside of where the composition is undefined, of course).

Exercise 20 Letbe a holomorphic map from the Riemann sphere to itself. Show that

is either identically

, or is a rational function in the sense that there exist polynomials

of one complex variable, with

not identically zero, such that

for all

with

. (Hint: show that

has finitely many poles, and eliminate them by multiplying

by appropriate linear factors. Then use Exercise 31 from Notes 3.)

Exercise 21 (Partial fractions) Letbe a polynomial of one complex variable, which by the fundamental theorem of algebra we may write as

for some distinct roots

, some non-zero

, and some positive integers

. Let

be another polynomial of one complex variable. Show that there exist unique polynomials

, with each

having degree less than

for

, such that one has the partial fraction decomposition

for all

. Furthermore, show that

vanishes if the degree

of

is less than the degree

of

, and has degree

otherwise.

— 2. The residue theorem —

Now we can prove a significant generalisation of the Cauchy theorem and Cauchy integral formula, known as the residue theorem.

Suppose one has a function holomorphic on an open set

outside of a closed singular set

. If

is an isolated singularity of

, then we have a Laurent expansion

We then have

Theorem 22 (Residue theorem) Letbe a simply connected open set, and let

be holomorphic outside of a closed discrete singular set

(thus all singularities in

are isolated singularities). Let

be a closed curve in

. Then

where only finitely many of the terms on the right-hand side are non-zero.

Proof: Being simply connected, can be contracted to a point inside

. This homotopy takes values inside some compact subset

of

, and thus only contains finitely many of the singularities in

. By Rouche’s theorem for winding number (Corollary 44 from Notes 3), the winding number

then vanishes for any singularity

in

(since

can be contracted to a point without touching

). Hence on the right-hand side we may replace

by

without loss of generality.

Next, we exploit the linearity of the residue theorem in to reduce to the case where all the residues

vanish. We introduce the rational function

defined by

Now we repeat the proof of Cauchy’s theorem (Theorem 4 of Notes 3), discretising the homotopy into short closed polygonal paths

(each of diameter less than

) around which the integral of

is zero, to conclude (9). The argument is completely analogous, save for the technicality that the paths

may occasionally pass through one of the points in

. But this can be easily rectified by perturbing each of the paths

by adding a short detour around any point of

that is passed through; we leave the details to the interested reader.

Combining the residue theorem with the Jordan curve theorem, we obtain the following special case, which is already enough for many applications:

Corollary 23 (Residue theorem for simple closed curves) Letbe a simple closed anticlockwise curve in

. Suppose that

is holomorphic on an open set

containing the image and interior of

, outside of a closed discrete

that does not intersect the image of

. Then we have

If

is oriented clockwise instead of anticlockwise, then we instead have

Exercise 24 (Homology version of residue theorem) Show that the residue theorem continues to hold when the closed curveis replaced by a

-cycle (as in Exercise 15 of Notes 3) that avoids all the singularities in

, and the requirement that

be simply connected is replaced by the requirement that

contains all the points

outside of the image of

where

.

Exercise 25 (Exterior version of residue theorem) Letbe a simple closed anticlockwise curve in

. Suppose that

is holomorphic on an open set

containing the image and exterior of

, outside of a finite

that does not intersect the image of

. Suppose also that

converges to a finite limit

in the limit

. Show that

If

is oriented clockwise instead of anticlockwise, show instead that

In order to use the residue theorem effectively, one of course needs some tools to compute the residue at a given point. The Fourier inversion formula (5) expresses such residues as a contour integral, but this is not so useful in practice as often the best way to compute such integrals is via the residue theorem, leaving one back where one started! But if the singularity is not an essential one, we have some useful formulae:

Exercise 26 Letbe holomorphic on an open set

outside of a closed singular set

, and let

be an isolated point of

.

Using these facts, show that Cauchy’s theorem (Theorem 14 from Notes 3), the Cauchy integral formula (Theorem 39 from Notes 3), and the higher order Cauchy integral formula (Exercise 42 from Notes 3) can be derived from the residue theorem. (Of course, this is not an independent proof of these theorems, as they were used in the proof of the residue theorem!)

- (i) If

has a removable singularity at

, show that

.

- (ii) If

has a simple pole at

, show that

.

- (iii) If

has a pole of order at most

at

for some

, show that

In particular, if

near

for some

that is holomorphic at

, then

The residue theorem can be applied in countless ways; we give only a small sample of them below.

Exercise 27 Use the residue theorem to give an alternate proof of the fundamental theorem of algebra, by considering the integralfor a polynomial

of degree

and some large radius

.

Exercise 28 Letbe a Dirichlet polynomial of the form

for some sequence

of complex numbers, with only finitely many of the

non-zero. Establish Perron’s formula

for any real numbers

with

not an integer. What happens if

is an integer? Generalisations and variants of this formula, particularly with the Dirichlet polynomial replaced by more general Dirichlet series in which infinitely many of the

are allowed to be non-zero, are of particular use in analytic number theory; see for instance this previous blog post.

Exercise 29 (Spectral theorem for matrices) This exercise presumes some familiarity with linear algebra. Letbe a positive integer, and let

denote the ring of

complex matrices. Let

be a matrix in

. The characteristic polynomial

, where

is the

identity matrix, is a polynomial of degree

in

with leading coefficient

; we let

be the distinct zeroes of this polynomial, and let

be the multiplicities; thus by the fundamental theorem of algebra we have

We refer to the set

as the spectrum of

. Let

be any closed anticlockwise curve that contains the spectrum of

in its interior, and let

be an open subset of

that contains

and its interior.

- (i) Show that the resolvent

is a meromorphic function on

with poles at the spectrum of

, where we call a matrix-valued function meromorphic if each of its

components are meromorphic. (Hint: use the adjugate matrix.)

- (ii) For any holomorphic

, we define the matrix

by the formula

(cf. the Cauchy integral formula). We refer to

as the holomorphic functional calculus for

applied to

. Show that the matrix

does not depend on the choice of

, depends linearly on

, and equals the identity matrix when

is the constant function

. Furthermore, if

is the function

, show that

Conclude in particular that if

is a polynomial

with complex coefficients

, then the function

(as defined by the holomorphic functional calculus) matches how one would define

algebraically, in the sense that

- (iii) Prove the Cayley-Hamilton theorem

. (Note from (ii) that it does not matter whether one interprets

algebraically, or via the holomorphic functional calculus.)

- (iv) If

is holomorphic, show that the matrix-valued function

has only removable singularities in

.

- (v) If

are holomorphic, establish the identity

- (vi) Show that there exist matrices

that are idempotent (thus

for all

), commute with each other and with

, sum to the identity (thus

), annihilate each other (thus

for all distinct

) and are such that for each

, one has the nilpotency property

In particular, we have the spectral decomposition

where each

is a nilpotent matrix with

. Finally, show that the range of

(viewed as a linear operator from

to itself) has dimension

. Find a way to interpret each

as the (negative of the) “residue” of the resolvent operator

at

.

Under some additional hypotheses, it is possible to extend the analysis in the above exercise to infinite-dimensional matrices or other linear operators, but we will not do so here.

— 3. The argument principle —

We have not yet defined the complex logarithm of a complex number

, but one of the properties we would expect of this logarithm is that its derivative should be the reciprocal function:

. In particular, by the chain rule we would expect the formula

A general rule of thumb in complex analysis is that holomorphic functions behave like generalisations of polynomials, and meromorphic functions behave like generalisations of rational functions. In view of this rule of thumb and the above calculation, the following lemma should thus not be surprising:

Lemma 30 Letbe a holomorphic function on an open set

outside of a closed singular set

, and let

be either an element of

or an isolated point of

.

- (i) If

is holomorphic and non-zero at

, then the log-derivative

is also holomorphic at

.

- (ii) If

is holomorphic at

with a zero of order

, then the log-derivative

has a simple pole at

with residue

.

- (iii) If

has a removable singularity at

, and is non-zero once the singularity is removed, then the log-derivative

has a removable singularity at

.

- (iv) If

has a removable singularity at

, and has a zero of order

once the singularity is removed, then the log-derivative

has a simple pole at

with residue

.

- (v) If

has a pole of order

at

, then the log-derivative

has a simple pole at

with residue

.

Proof: The claim (i) is obvious. For (ii), we use Taylor expansion to factor for some

holomorphic and non-zero near

, and then from (11) we have

Remark 31 Note that the lemma does not cover all possible singularity and zero scenarios. For instance,could be identically zero, in which case the log-derivative is nowhere defined. If

has an essential singularity then the log-derivative can be a pole (as seen for instance by the example

for some

) or another essential singularity (as can be seen for instance by the example

). Finally, if

has a non-isolated singularity, then the log-derivative could exhibit a wide range of behaviour (but probably will be quite wild as one approaches the singular set).

By combining the above lemma with the residue theorem, we obtain the argument principle:

Theorem 32 (Argument principle) Letbe a simple closed anticlockwise curve. Let

be an open set containing

and its interior. Let

be a meromorphic function on

that is holomorphic and non-zero on the image of

. Suppose that after removing all the removable singularities of

,

has zeroes

in the interior of

(of orders

respectively), and poles

in the interior of

(of orders

respectively). (

is also allowed to have zeroes and poles in the exterior of

.) Then we have

where

is the closed curve

.

Proof: The first equality of (13) follows from the residue theorem and Lemma 30. From the change of variables formula (Exercise 17(ix) of Notes 2) we have

We isolate the special case of the argument principle when there are no poles for special mention:

Corollary 33 (Special case of argument principle) Letbe a simple closed anticlockwise curve, let

be an open set containing the image of

and its interior, and let

be holomorphic. Suppose that

has no zeroes on the image of

. Then the number of zeroes of

(counting multiplicity) in the interior of

is equal to the winding number

of

around the origin.

Recalling that the winding number is a homotopy invariant (Lemma 43 of Notes 3), we conclude that the number of zeroes of a holomorphic function in the interior of a simple closed anticlockwise curve is also invariant with respect to continuous perturbations, so long as zeroes never cross the curve itself. More precisely:

Corollary 34 (Stability of number of zeroes) Letbe an open set. Let

,

be simple closed anticlockwise curves that are homotopic as closed curves via some homotopy

; suppose also that

contains the interiors of

and

. Let

be holomorphic, and let

be a continuous function such that

and

for all

. Suppose that

for all

and

(i.e., at time

, the curve

never encounters any zeroes of

). Then the number of zeroes (counting multiplicity) of

in the interior of

equals the number of zeroes of

in the interior of

(counting multiplicity).

Proof: By Corollary 33, it suffices to show that

Informally, the above corollary asserts that zeroes of holomorphic functions cannot be created or destroyed, as long as they are confined within a closed curve.

Example 35 Letbe the unit circle

. The polynomial

has a double zero at

, so (counting multiplicity) has two zeroes in the interior of

. If we consider instead the perturbation

for some

, this has simple zeroes at

and

respectively, so as long as

, the holomorphic function

also has two zeroes in the interior of

; but as

crosses

, the zeroes of

pass through

, and one no longer has any zeroes of

in the interior of

. The situation can be contrasted with the real case: the function

has a double zero at the origin when

, but as soon as

becomes positive, the zeroes immediately disappear from the real line. Note that the stability of zeroes fails if we do not count zeroes with multiplicity; thus, as a general rule of thumb, one should always try to count zeroes with multiplicity when doing complex analysis. (Heuristically, one can think of a zero of order

as

simple zeroes that are “infinitesimally close together”.)

Example 36 When one considers meromorphic functions instead of holomorphic ones, then the number of zeroes inside a region need not be stable any more, but the number of zeroes minus the number of poles will be stable. Consider for instance the meromorphic function, which has a removable singularity at

but no zeroes or poles. If we perturb it to

for some

, then we suddenly have a double pole at

, but this is balanced by two simple zeroes at

and

; in the limit as

we see that the two zeroes “collide” with the double pole, annihilating both the zeroes and the poles.

A particularly useful special case of the stability of zeroes is Rouche’s theorem:

Theorem 37 (Rouche’s theorem) Letbe a simple closed curve, and let

be an open set containing the image of

and its interior. Let

be holomorphic. If one has

for all

in the image of

, then

and

have the same number of zeroes (counting multiplicity) in the interior of

.

Proof: We may assume without loss of generality that is anticlockwise. By hypothesis,

and

cannot have zeroes on the image of

. The claim then follows from Corollary 34 with

,

,

,

, and

.

Rouche’s theorem has many consequences for complex analysis. One basic consequence is the open mapping theorem:

Theorem 38 (Open mapping theorem) Letbe an open connected non-empty subset of

, and let

be holomorphic and not constant. Then

is also open.

Proof: Let . As

is not constant, the zeroes of

are isolated (Corollary 26 of Notes 3). Thus, for

sufficiently small,

is nonvanishing on the image of the circle

. Clearly

has at least one zero in the interior of this circle. Thus, by Rouche’s theorem, if

is sufficiently close to

, then

will also have at least one zero in the interior of this circle. In particular,

contains a neighbourhood of

, and the claim follows.

Exercise 39 Use Rouche’s theorem to obtain another proof of the fundamental theorem of algebra, by showing that a polynomialwith

and

has exactly

zeroes (counting multiplicity) in the complex plane. (Hint: compare

with

inside some large circle

.)

Exercise 40 (Inverse function theorem) Letbe an open subset of

, let

, and let

be a holomorphic function such that

. Show that there exists a neighbourhood

of

in

such that the map

is a complex diffeomorphism; that is to say, it is holomorphic, invertible, and the inverse is also holomorphic. Finally, show that

for all

. (Hint: one can either mimic the real-variable proof of the inverse function theorem using the contraction mapping theorem, or one can use Rouche’s theorem and the open mapping theorem to construct the inverse.)

Exercise 41 Letbe an open subset of

, and

be a map. Show that the following are equivalent:

- (i)

is a local complex diffeomorphism. That is to say, for every

there is a neighbourhood

of

in

such that

is open and

is a complex diffeomorphism (as defined in the preceding exercise).

- (ii)

is holomorphic on

and is a local homeomorphism. That is to say, for every

there is a neighbourhood

of

in

such that

is open and

is a homeomorphism.

- (iii)

is holomorphic on

and is locally injective. That is to say, for every

there is a neighbourhood

of

in

such that

is injective.

- (iv)

is holomorphic on

, and the derivative

is nowhere vanishing.

Exercise 42 (Hurwitz’s theorem) Letbe an open connected non-empty subset of

, and let

be a sequence of holomorphic functions that converge uniformly on compact sets to a limit

(which is then necessarily also holomorphic, thanks to Theorem 36 of Notes 3). Prove the following two versions of Hurwitz’s theorem:

- (i) If none of the

have any zeroes in

, show that either

also has no zeroes in

, or is identically zero.

- (ii) If all of the

are univalent (that is to say, they are injective holomorphic functions), show that either

is also univalent, or is constant.

Exercise 43 (Bloch’s theorem) The purpose of this exercise is to establish a more quantitative variant of the open mapping theorem, due to Bloch; this will be useful later in this notes for proving the Picard and Montel theorems. Letbe a holomorphic function on a disk

, and suppose that

is non-zero

- (i) Suppose that

for all

. Show that there is an absolute constant

such that

contains the disk

. (Hint: one can normalise

,

,

. Use the higher order Cauchy integral formula to get some bound on

for

near the origin, and use this to approximate

by

near the origin. Then apply Rouche’s theorem.)

- (ii) Without the hypothesis in (i), show that there is an absolute constant

such that

contains a disk of radius

. (Hint: if one has

for all

, then we can apply (i) with

replaced by

. If not, pick

with

, and start over with

replaced by

and

replaced by

. One cannot iterate this process indefinitely as it will create a singularity of

in

.)

— 4. Branches of the complex logarithm —

We have refrained until now from discussing one of the most basic transcendental functions in complex analysis, the complex logarithm. In real analysis, the real logarithm can be defined as the inverse of the exponential function

; it can also be equivalently defined as the antiderivative of the function

, with the initial condition

. (We use

here for the real logarithm in order to distinguish it from the complex logarithm below.)

Let’s see what happens when one tries to extend these definitions to the complex domain. We begin with the inversion of the complex exponential. From Euler’s formula we have that ; more generally, we have

whenever

for some integer

. In particular, the exponential function

is not injective. Indeed, for any non-zero

, we have a multi-valued logarithm

Of course, one also encounters multi-valued functions in real analysis, starting when one tries to invert the squaring function , as any given positive number

has two square roots. In the real case, one can eliminate this multi-valuedness by picking a branch of the square root function – a function which selects one of the multiple choices for that function at each point in the domain. In particular, we have the positive branch

of the square root function on

, as well as the negative branch

. One could also create more discontinuous branches of the square root function, for instance the function that sends

to

for

, and

to

for

. In the complex case it will often be appropriate to only construct branches on some subset of the domain of definition, in order to retain good properties of the branch, such as holomorphicity.

Suppose now that we have a branch of the logarithm function, thus

is an open subset of

and

On the other hand, if is a simply connected open subset of

, then from Cauchy’s theorem the function

is conservative on

. If we pick a point

in

and arbitrarily select a logarithm

of

, we can then use the fundamental theorem of calculus to find an antiderivative

of

on

with

. By definition,

is holomorphic, and from the chain rule we have for all

that

Thus, for instance, the region formed by excluding the negative real axis from the complex plane is simply connected (it is star-shaped around

), and so must admit a holomorphic branch of the complex logarithm. One such branch is the standard branch

of the complex logarithm, defined as

Exercise 44 Letbe a connected non-empty open subset of

.

- (i) If

and

are continuous branches of the complex logarithm, show that there exists a natural number

such that

for all

.

- (ii) Show that any continuous branch

of the complex logarithm is holomorphic.

- (iii) Show that there is a continuous branch

of the logarithm if and only if

and

lie in the same connected component of

. (Hint: for the “if” direction, use a continuity argument to show that the winding number of any closed curve in

around

vanishes. For the “only if”, you may use without proof the fact that if two points

in a compact Hausdorff space

do not lie in the same connected component, then there exists a clopen subset

of

that contains

but not

(sketch of proof: show that the intersection of all the clopen neighbourhoods of

is connected and also contains all the connected sets containing

). Use this fact to encircle

by a simple polygonal path in

.)

Exercise 45 Letbe a continuous injective map with

and

as

.

- (i) Show that

is not all of

. (Hint: modify the construction in Section 4 of Notes 3 that showed that a simple closed curve admitted at least one point with non-zero winding number.)

- (ii) Show that the complement

is simply connected. (Hint: modify the remaining arguments in Section 4 of Notes 3). In particular, by the preceding discussion, there is a branch of the complex logarithm that is holomorphic outside of

.

It is instructive to view the identity

, through the lens of branches of the complex logarithm such as the standard branch

One can use branches of the complex logarithm to create branches of the root functions

for natural numbers

. As with the complex exponential, the function

is not injective, and so

is multivalued (see Exercise 15 of Notes 0). One cannot form a continuous branch of this function on

for any

, as the corresponding branch of

would then contradict the quantisation of order of singularities (Exercise 14). However, on any domain

where there is a holomorphic branch

of the complex logarithm, one can define a holomorphic branch

of the

root function by the formula

The presence of branch cuts can prevent one from directly applying the residue theorem to calculate integrals involving branches of multi-valued functions. But in some cases, the presence of the branch cut can actually be exploited to compute an integral. The following exercise provides an example:

Exercise 46 Compute the improper integralby applying the residue theorem to the function

for some branch

of

with branch cut on the positive real axis, and using a “keyhole” contour that is a perturbation of

the key point is that the branch cut makes the contribution of (the perturbations) of

and

fail to cancel each other.

The construction of holomorphic branches of can be extended to other logarithms:

Exercise 47 Letbe a simply connected subset of

, and let

be a holomorphic function with no zeroes on

.

- (i) Show that there exists a holomorphic branch

of the complex logarithm

, thus

. Furthermore, this branch is unique up to the addition of an integer multiple of

(i.e., if

are two such branches, then

for some integer

).

- (ii) Show that for any natural number

, there exists a holomorphic branch

of the root function

, thus

.

Actually, one can invert other non-injective holomorphic functions than the complex exponential, provided that these functions are a covering map. We recall this topological concept:

Definition 48 (Covering map) Letbe a continuous map between two connected topological spaces

. We say that

is a covering map if, for each

, there exists an open neighbourhood

of

in

such that the preimage

is the disjoint union of open subsets

of

, such that for each

, the map

is a homeomorphism. In this situation, we call

a covering space of

.

In complex analysis, one specialises to the situation in which are Riemann surfaces (e.g. they could be open subsets of

), and

is a holomorphic map. In that case, the homeomorphisms

are in fact complex diffeomorphisms, thanks to Exercise 41.

Example 49 The exponential mapis a covering map, because for any element of

written in polar form as

, one can pick (say) the neighbourhood

of

, and observe that the preimage

of

is the disjoint union of the open sets

for

, and that the exponential map

is a diffeomorphism. A similar calculation shows that for any natural number

, the map

is a covering map from

to

. However, the map

is not a covering map from

to

, because it fails to be a local diffeomorphism at zero due to the vanishing derivative (here we use Exercise 41). One final (non-)example: the map

is not a covering map from the upper half-plane

to

, because the preimage of any small disk

around

splits into two disconnected regions, and only one of them is homeomorphic to

via the map

.

From topology we have the following lifting property:

Lemma 50 (Lifting lemma) Letbe a continuous covering map between two path-connected and locally path-connected topological spaces

. Let

be a simply connected and path connected topological space, and let

be continuous. Let

, and let

be such that

. Then there exists a unique continuous map

such that

and

, which we call a lift of

by

.

Proof: We first verify uniqueness. If we have two continuous functions with

and

, then the set

is clearly closed in

and contains

. From the covering map property we also see that

is open, and hence by connectedness we have

on all of

, giving the claim.

To verify existence of the lift, we first prove the existence of monodromy. More precisely, given any curve with

we show that there exists a unique curve

such that

and

(the reader is encouraged to draw a picture to describe this situation). Uniqueness follows from the connectedness argument used to prove uniqueness of the lift

, so we turn to existence. As in previous notes, we rely on a continuity argument. Let

be the set of all

for which there exists a curve

such that

and

, where

is the restriction of

to

. Clearly

contains

; using the covering map property (and the uniqueness of lifts) it is not difficult to show that

is also open and closed in

. Thus

is all of

, giving the claim.

Now let ,

be homotopic curves with fixed endpoints, with initial point

and some terminal point

, and let

be a homotopy. For each

, we have a curve

given by

, and by the preceding paragraph we can associate a curve

such that

and

. Another application of the continuity method shows that for all

, the map

is continuous; in particular, the map

is continuous. On the other hand,

lies in

, which is a discrete set thanks to the covering map property. We conclude that

is constant in

, and in particular that

.

Since is simply connected, any two curves

with fixed endpoints are homotopic. We can thus define a function

by declaring

for any

to be the point

, where

is any curve from

to

, and

is constructed as before. By construction we have

, and from the local path connectedness of

and the covering map property of

we can check that

is continuous. The claim follows.

We can specialise this to the complex case and obtain

Corollary 51 (Holomorphic lifting lemma) Letbe a holomorphic covering map between two connected Riemann surfaces

. Let

be a simply connected and path connected Riemann surface, and let

be holomorphic. Let

, and let

be such that

. Then there exists a unique holomorphic map

such that

and

, which we call a lift of

by

.

Proof: A Riemann surface is automatically locally path-connected, and a connected Riemann surface is automatically path connected (observe that the set of all points on the surface that can be path-connected to a reference point is open, closed, and non-empty). Applying Lemma 50, we obtain all the required claims, except that the lift

produced is only known to be continuous rather than holomorphic. But then we can locally express

as the composition of one of the local inverses of

with

. Applying Exercise 41, these local inverses are holomorphic, and so

is holomorphic also.

Remark 52 It is also possible to establish the above corollary using the monodromy theorem and analytic continuation.

Exercise 53 Establish Exercise 47 using Corollary 51.

Exercise 54 Letbe simply connected, and let

be holomorphic and avoid taking the values

. Show that there exists a holomorphic function

such that

. (This can be proven either through Corollary 51, or by using the quadratic formula to solve for

and then applying Exercise 47.)

In some cases it is also possible to obtain lifts in non-simply connected domains:

Exercise 55 Show that there exists a holomorphic functionsuch that

for all

. (Hint: use the Schwarz reflection principle, see Exercise 39 of Notes 3.)

As an illustration of what one can do with all this machinery, let us now prove the Picard theorems. We begin with the easier “little” Picard theorem.

Theorem 56 (Little Picard theorem) Letbe entire and non-constant. Then

omits at most one point of

.

The example of the exponential function , whose range omits the origin, shows that one cannot make any stronger conclusion about

.

Proof: Suppose for contradiction that we have an entire non-constant function such that

omits at least two points. After applying a linear transformation, we may assume that

avoids

and

, thus

takes values in

.

At this point, the most natural thing to do from a Riemann surface point of view would be to cover by a bounded region, so that Liouville’s theorem may be applied. This can be done easily once one has the machinery of elliptic functions; but as we do not have this machinery yet, we will instead use a more ad hoc covering of

using the exponential and trigonometric functions to achieve a passable substitute for this strategy.

We turn to the details. Since avoids

, we may apply Exercise 47 to write

for some entire

. As

avoids

,

must avoid the integers

.

Next, we apply Exercise 54 to write for some entire

. The set

must now avoid all complex numbers of the form

for natural numbers

and integers

. In particular, if

is large enough, we see that

does not contain any disk of the form

. Applying Bloch’s theorem (Exercise 43(ii)) in the contrapositive, we conclude that for any disk

in

, one has

for some absolute constant

. Sending

to infinity and using the fundamental theorem of calculus, we conclude that

is constant, hence

and

are also constant, a contradiction.

Now we prove the more difficult “great” Picard theorem.

Theorem 57 (Great Picard theorem) Letbe holomorphic on a disk

outside of a singularity at

. If this singularity is essential, then

omits at most one point of

.

Note that if one only has a pole at , e.g. if

for some natural number

, then the conclusion of the great Picard theorem fails. This result easily implies both the little Picard theorem (because if

is entire and non-polynomial, then

has an essential singularity at the origin) and the Casorati-Weierstrass theorem (Theorem 12(iii)). By repeatedly passing to smaller neighbourhoods, one in fact sees that with at most one exception, every complex number

is attained infinitely often by a function holomorphic in a punctured disk around an essential singularity.

Proof: This will be a variant of the proof of the little Picard theorem; it would again be more natural to use elliptic functions, but we will use some passable substitutes for such functions concocted in an ad hoc fashion out of exponential and trigonometric functions.

Assume for contradiction that has an essential singularity at

and avoids at least two points in

. Applying linear transformations to both the domain and range of

, we may normalise

,

, and assume that

avoids

and

, thus we have a holomorphic map

with an essential singularity at

.

The domain is not simply connected, so we work instead with the function

On the other hand, from (16) one has

We now upgrade this bound on (18) by exploiting the quantisation of pole orders (Exercise 14). As the function is periodic with period

on

, we may write

Exercise 58 (Montel’s theorem) Letbe an open subset of the complex plane. Define a holomorphic normal family on

to be a collection

of holomorphic functions

with the following property: given any sequence

in

, there exists a subsequence

which is uniformly convergent on compact sets (i.e., for every compact subset

of

, the sequence

converges uniformly on

to some limit). Similarly, define a meromorphic normal family to be a collection

of meromorphic functions

such that for any sequence

in

, there exists a subsequence

that are uniformly convergent on compact sets, using the metric on the Riemann sphere induced by the identification with the geometric sphere

. (More succinctly, normal families are those families of holomorphic or meromorphic functions that are precompact in the locally uniform topology.)

- (i) (Little Montel theorem) Suppose that

is a collection of holomorphic functions

that are uniformly bounded on compact sets (i.e., for each compact

there exists a constant

such that

for all

and

). Show that

is a holomorphic normal family. (Hint: use the higher order Cauchy integral formula to establish some equicontinuity on this family on compact sets, then use the Arzelá-Ascoli theorem.

- (ii) (Great Montel theorem) Let

be three distinct elements of the Riemann sphere, and suppose that

is a family of meromorphic functions

which avoid the three points

. Show that

is a meromorphic normal family. (Hint: use some elementary transformations to reduce to the case

. Then, as in the proof of the Picard theorems, express each element

of

locally in the form

and use Bloch’s theorem to get some uniform bounds on

.)

Exercise 59 (Harnack principle) Letbe an open connected subset of

, and let

be a sequence of harmonic functions which is pointwise nondecreasing (thus

for all

and

). Show that

is either infinite everywhere on

, or is harmonic. (Hint: work locally in a disk. Write each

on this disk as the real part of a holomorphic function

, and apply Montel’s theorem followed by the Hurwitz theorem to

.) This result is known as Harnack’s principle.

Exercise 60

- (i) Show that the function

is harmonic on

but has no harmonic conjugate.

- (ii) Let

, and let

be a harmonic function obeying the bounds

for all

and some constants

. Show that there exists a real number

and a harmonic function

such that

for all

. (Hint: one can find a conjugate of

outside of some branch cut, say the negative real axis restricted to

. Adjust

by a multiple of

until the conjugate becomes continuous on this branch cut.)

Exercise 61 (Local description of holomorphic maps) Letbe a holomorphic function on an open subset

of

, let

be a point in

, and suppose that

has a zero of order

at

for some

. Show that there exists a neighbourhood

of

in

on which one has the factorisation

, where

is holomorphic with a simple zero at

(and hence a complex diffeomorphism from a sufficiently small neighbourhood of

to a neighbourhood of

). Use this to give an alternate proof of the open mapping theorem (Theorem 38).

Exercise 62 (Winding number and lifting) Let, let

be a closed curve avoiding

, and let

be an integer. Show that the following are equivalent:

- (i)

.

- (ii) There exists a complex number

and a curve

from

to

such that

for all

.

- (iii)

is homotopic up to reparameterisation as closed curves in

to the curve

that maps

to

for some

.

181 comments

Comments feed for this article

5 May, 2022 at 6:24 am

J

In theorem 12, is assumed to be an open subset of

assumed to be an open subset of  or the Riemann sphere

or the Riemann sphere  ? Or for arbitrary Riemann surfaces? [In

? Or for arbitrary Riemann surfaces? [In  , since the Riemann sphere or other Riemann surfaces have not been introduced yet. However, it is not difficult to extend this theorem to those settings by using appropriate coordinate charts. -T]

, since the Riemann sphere or other Riemann surfaces have not been introduced yet. However, it is not difficult to extend this theorem to those settings by using appropriate coordinate charts. -T]

5 May, 2022 at 12:37 pm

Anonymous

Typo in

… we see that has an antiderivative in this punctured disk, namely

has an antiderivative in this punctured disk, namely

The exponent on is

is  .

.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

5 May, 2022 at 12:40 pm

J

[This is a natural variation of the same notation used for other infinite sums such as . -T]

. -T]