I’ve just uploaded to the arXiv my paper “An integration approach to the Toeplitz square peg problem“, submitted to Forum of Mathematics, Sigma. This paper resulted from my attempts recently to solve the Toeplitz square peg problem (also known as the inscribed square problem):

Conjecture 1 (Toeplitz square peg problem) Let

be a simple closed curve in the plane. Is it necessarily the case that

contains four vertices of a square?

See this recent survey of Matschke in the Notices of the AMS for the latest results on this problem.

The route I took to the results in this paper was somewhat convoluted. I was motivated to look at this problem after lecturing recently on the Jordan curve theorem in my class. The problem is superficially similar to the Jordan curve theorem in that the result is known (and rather easy to prove) if is sufficiently regular (e.g. if it is a polygonal path), but seems to be significantly more difficult when the curve is merely assumed to be continuous. Roughly speaking, all the known positive results on the problem have proceeded using (in some form or another) tools from homology: note for instance that one can view the conjecture as asking whether the four-dimensional subset

of the eight-dimensional space

necessarily intersects the four-dimensional space

consisting of the quadruples

traversing a square in (say) anti-clockwise order; this space is a four-dimensional linear subspace of

, with a two-dimensional subspace of “degenerate” squares

removed. If one ignores this degenerate subspace, one can use intersection theory to conclude (under reasonable “transversality” hypotheses) that

intersects

an odd number of times (up to the cyclic symmetries of the square), which is basically how Conjecture 1 is proven in the regular case. Unfortunately, if one then takes a limit and considers what happens when

is just a continuous curve, the odd number of squares created by these homological arguments could conceivably all degenerate to points, thus blocking one from proving the conjecture in the general case.

Inspired by my previous work on finite time blowup for various PDEs, I first tried looking for a counterexample in the category of (locally) self-similar curves that are smooth (or piecewise linear) away from a single origin where it can oscillate infinitely often; this is basically the smoothest type of curve that was not already covered by previous results. By a rescaling and compactness argument, it is not difficult to see that such a counterexample would exist if there was a counterexample to the following periodic version of the conjecture:

Conjecture 2 (Periodic square peg problem) Let

be two disjoint simple closed piecewise linear curves in the cylinder

which have a winding number of one, that is to say they are homologous to the loop

from

to

. Then the union of

and

contains the four vertices of a square.

In contrast to Conjecture 1, which is known for polygonal paths, Conjecture 2 is still open even under the hypothesis of polygonal paths; the homological arguments alluded to previously now show that the number of inscribed squares in the periodic setting is even rather than odd, which is not enough to conclude the conjecture. (This flipping of parity from odd to even due to an infinite amount of oscillation is reminiscent of the “Eilenberg-Mazur swindle“, discussed in this previous post.)

I therefore tried to construct counterexamples to Conjecture 2. I began perturbatively, looking at curves that were small perturbations of constant functions. After some initial Taylor expansion, I was blocked from forming such a counterexample because an inspection of the leading Taylor coefficients required one to construct a continuous periodic function of mean zero that never vanished, which of course was impossible by the intermediate value theorem. I kept expanding to higher and higher order to try to evade this obstruction (this, incidentally, was when I discovered this cute application of Lagrange reversion) but no matter how high an accuracy I went (I think I ended up expanding to sixth order in a perturbative parameter

before figuring out what was going on!), this obstruction kept resurfacing again and again. I eventually figured out that this obstruction was being caused by a “conserved integral of motion” for both Conjecture 2 and Conjecture 1, which can in fact be used to largely rule out perturbative constructions. This yielded a new positive result for both conjectures:

We sketch the proof of Theorem 3(i) as follows (the proof of Theorem 3(ii) is very similar). Let be the curve

, thus

traverses one of the two graphs that comprise

. For each time

, there is a unique square with first vertex

(and the other three vertices, traversed in anticlockwise order, denoted

) such that

also lies in the graph of

and

also lies in the graph of

(actually for technical reasons we have to extend

by constants to all of

in order for this claim to be true). To see this, we simply rotate the graph of

clockwise by

around

, where (by the Lipschitz hypotheses) it must hit the graph of

in a unique point, which is

, and which then determines the other two vertices

of the square. The curve

has the same starting and ending point as the graph of

or

; using the Lipschitz hypothesis one can show this graph is simple. If the curve ever hits the graph of

other than at the endpoints, we have created an inscribed square, so we may assume for contradiction that

avoids the graph of

, and hence by the Jordan curve theorem the two curves enclose some non-empty bounded open region

.

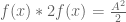

Now for the conserved integral of motion. If we integrate the -form

on each of the four curves

, we obtain the identity

This identity can be established by the following calculation: one can parameterise

for some Lipschitz functions ; thus for instance

. Inserting these parameterisations and doing some canceling, one can write the above integral as

which vanishes because (which represent the sidelengths of the squares determined by

vanish at the endpoints

.

Using this conserved integral of motion, one can show that

which by Stokes’ theorem then implies that the bounded open region mentioned previously has zero area, which is absurd.

This argument hinged on the curve being simple, so that the Jordan curve theorem could apply. Once one left the perturbative regime of curves of small Lipschitz constant, it became possible for

to be self-crossing, but nevertheless there still seemed to be some sort of integral obstruction. I eventually isolated the problem in the form of a strengthened version of Conjecture 2:

Conjecture 4 (Area formulation of square peg problem) Let

be simple closed piecewise linear curves of winding number

obeying the area identity

(note the

-form

is still well defined on the cylinder

; note also that the curves

are allowed to cross each other.) Then there exists a (possibly degenerate) square with vertices (traversed in anticlockwise order) lying on

respectively.

It is not difficult to see that Conjecture 4 implies Conjecture 2. Actually I believe that the converse implication is at least morally true, in that any counterexample to Conjecture 4 can be eventually transformed to a counterexample to Conjecture 2 and Conjecture 1. The conserved integral of motion argument can establish Conjecture 4 in many cases, for instance if are graphs of functions of Lipschitz constant less than one.

Conjecture 4 has a model special case, when one of the is assumed to just be a horizontal loop. In this case, the problem collapses to that of producing an intersection between two three-dimensional subsets of a six-dimensional space, rather than to four-dimensional subsets of an eight-dimensional space. More precisely, some elementary transformations reveal that this special case of Conjecture 4 can be formulated in the following fashion in which the geometric notion of a square is replaced by the additive notion of a triple of real numbers summing to zero:

Conjecture 5 (Special case of area formulation) Let

be simple closed piecewise linear curves of winding number

obeying the area identity

Then there exist

and

with

such that

for

.

This conjecture is easy to establish if one of the curves, say , is the graph

of some piecewise linear function

, since in that case the curve

and the curve

enclose the same area in the sense that

, and hence must intersect by the Jordan curve theorem (otherwise they would enclose a non-zero amount of area between them), giving the claim. But when none of the

are graphs, the situation becomes combinatorially more complicated.

Using some elementary homological arguments (e.g. breaking up closed -cycles into closed paths) and working with a generic horizontal slice of the curves, I was able to show that Conjecture 5 was equivalent to a one-dimensional problem that was largely combinatorial in nature, revolving around the sign patterns of various triple sums

with

drawn from various finite sets of reals.

Conjecture 6 (Combinatorial form) Let

be odd natural numbers, and for each

, let

be distinct real numbers; we adopt the convention that

. Assume the following axioms:

- (i) For any

, the sums

are non-zero.

- (ii) (Non-crossing) For any

and

with the same parity, the pairs

and

are non-crossing in the sense that

- (iii) (Non-crossing sums) For any

,

,

of the same parity, one has

Then one has

Roughly speaking, Conjecture 6 and Conjecture 5 are connected by constructing curves to connect

to

for

by various paths, which either lie to the right of the

axis (when

is odd) or to the left of the

axis (when

is even). The axiom (ii) is asserting that the numbers

are ordered according to the permutation of a meander (formed by gluing together two non-crossing perfect matchings).

Using various ad hoc arguments involving “winding numbers”, it is possible to prove this conjecture in many cases (e.g. if one of the is at most

), to the extent that I have now become confident that this conjecture is true (and have now come full circle from trying to disprove Conjecture 1 to now believing that this conjecture holds also). But it seems that there is some non-trivial combinatorial argument to be made if one is to prove this conjecture; purely homological arguments seem to partially resolve the problem, but are not sufficient by themselves.

While I was not able to resolve the square peg problem, I think these results do provide a roadmap to attacking it, first by focusing on the combinatorial conjecture in Conjecture 6 (or its equivalent form in Conjecture 5), then after that is resolved moving on to Conjecture 4, and then finally to Conjecture 1.

29 comments

Comments feed for this article

23 November, 2016 at 2:46 am

Simple unsolved math problem, 2 | Yet Another Mathblog

[…] Added 2016-11-23: See also this recent post by T. Tao. […]

23 November, 2016 at 3:26 am

Anonymous

Abstract: “ including a a periodic” –> “ including a periodic”

[Thanks, this will be corrected in the next revision of the ms. -T.]

23 November, 2016 at 8:18 am

HUMBERTO T.

Revisar, aplicación “g”, conjetura (ii), teorema 3.

[Corregido, gracias – T.]

23 November, 2016 at 8:51 am

kevinburri

In part (ii) of Conjecture 6, should it be “q<=k_i" instead of "q<=k_1"?

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

23 November, 2016 at 11:47 am

Will

How large can $k_1$ get in your ad hoc arguments if $k_1=k_2=k_3$? I wonder if a computational method would be feasible for extending the range of applicability.

23 November, 2016 at 12:28 pm

Terence Tao

I did not systematically check all the cases of low , but I imagine it would be fairly straightforward to verify the case

, but I imagine it would be fairly straightforward to verify the case  for instance numerically (it is a linear programming problem, albeit a non-convex one).

for instance numerically (it is a linear programming problem, albeit a non-convex one).

26 November, 2016 at 8:01 pm

Crust

Is it a linear programming problem? Doesn’t the presence of the sgn function make it an integer programming problem?

23 November, 2016 at 1:20 pm

Anonymous

Consider a generalized form of this problem in which the Eucleadian metric is replaced by a Riemannian metric. Is it possible to apply your method to such generalized problem?

24 November, 2016 at 2:41 am

Adam Zsolt Wagner

A quick and rough computer search yielded no counterexamples to Conjecture 6.

I kept generating random arrays until they satisfied the conditions of the conjecture. Quite unsurprisingly, random arrays are very unlikely to satisfy the last condition so this algorithm is extremely slow. But this remarkably stupid approach was still sufficient to verify Conjecture 6 in about five hundred random instances of the case

until they satisfied the conditions of the conjecture. Quite unsurprisingly, random arrays are very unlikely to satisfy the last condition so this algorithm is extremely slow. But this remarkably stupid approach was still sufficient to verify Conjecture 6 in about five hundred random instances of the case  (and many thousands for smaller values of the

(and many thousands for smaller values of the  -s).

-s).

25 November, 2016 at 4:19 pm

allenknutson

“(I think I ended up expanding to sixth order in a perturbative parameter  before figuring out what was going on!)”

I get asked quite regularly “What’s it really like to work with Terry Tao?” and now I know what quote to point them to first.

26 November, 2016 at 5:11 pm

Ravi A. Bajaj

To be perfectly honest, I actually had more trouble with Jordan Curve Theorem than anything else I’ve encountered in my math education… I actually really worked hard on one of your exercises, Exercise 49 in Notes 3, a weekend about a month ago (Halloween time) but arrived at no conclusion and attempted to consult with a reputable classmate to no avail. I will simply say that we both agreed, after I was just really attempting to understand that exercise, that it was non-trivial that “for any Jordan curve \gamma, the closure of Int(\gamma) is just Int(\gamma) \cup \gamma.” So I imagine that I am not clear as to why \gamma cannot be space-filling. Not quite a reply to your post, but perhaps another return to the Jordan Curve Theorem’s difficulty in my opinion.

26 November, 2016 at 7:43 pm

Crust

Here‘s a nice elementary video on the (much easier) inscribed rectangle problem.

27 November, 2016 at 2:38 am

Anonymous

Absolutely beautiful video!

27 November, 2016 at 3:58 pm

Jhon Manugal

perhaps you mean the four vertex theorem which says “a simple, closed, smooth plane curve has at least four local extrema (specifically, at least two local maxima and at least two local minima)” E.g. an ellipse or circle or conchoid.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four-vertex_theorem

28 November, 2016 at 9:44 am

Eulogio Garcia

The square peg problem has a simple solution.

With the integration is very complex to give a solution because it is not asked that the square is inscribed in the curve.

Let’s go with the solution.

1º every simple closed curve does not nedd the four vértices of the square. Example all oval (not circle) of the function ;

;  .

.

2º In any closed curve we have that.

3º In any simple closed curve ( not oval).

Which implies that:

By point 2 follows that.

If along the whole curve this equality is met, the curve will not have the four vértices of the square.

Therefore we will have a where.

where.

And it is at this point that we will resume.

until the value of.

We know that always and therefore in one of them the following relationship will be fulfilled.

and therefore in one of them the following relationship will be fulfilled.

Abstract: If it is necessary the existence of the four vertices of the square in the simple closed curve; because if not, we are before and oval.

This came to be the demonstration by contradiction.

28 November, 2016 at 2:14 pm

Anonymous

In reference [17] I would probably remove “pp.” in order to use consistant notation.

[Thanks, this will be corrected in the next revision of the ms. -T]

30 November, 2016 at 8:29 am

Eulogio Garcia

Professor Tao, I thonk you may be interested to know what rally matters in my previous comment.

The relationship.

Where:

Your demonstration will be able to see it in.

International J. Math. computation Vol 28 (2) 2017.

You already know how to build with ruler and compass the angle the following is………..

the following is………..

30 November, 2016 at 9:31 am

Anonymous

Hi Professor. Tao,

Nice paper (‘An integration approach to the Toeplitz square peg problem’)! I’m confident your work will lead to more advance research and innovation in topology and in other related areas of mathematics. That’s a very positive development. Thank you! :-)

However, it may also be the result of over thinking the problem at hand. The Inscribed Square Problem (ISP) is difficult because the general Jordan curve may take countless forms. So we should seek out its invariant properties and apply our knowledge of analytic geometry (equations of parallel and perpendicular lines, and Pythagoras’s Theorem) and Euclidean geometry (similar or almost similar triangles with common diagonals, Law of sines and the Law of cosines, angular rotation about a point and translation from a point to another point).

I believe the first step is to inscribe the general Jordan curve (J) in a square box (B) with a diagonal whose endpoints are the two points on J that are farthest apart. And we define the center point (cp) of J as the intersection of the two diagonals of the B. And the work of analysis can begin here… And I believe the result should be affirmative! Good luck!

I believe I can have a tentative proof of ISP in less than a week. Wish me luck! :-)

30 November, 2016 at 2:56 pm

Anonymous

Let J’ be the complement object of J such that B = J’ + J.

Hmm. Let’s filled our square (B) with unit squares (s_1) and let’s assume our inscribed Jordan curve (J) does not have four points on it which form an inscribed square of any size from s_1 to s_n less than the size of B. We should expect a mix of square sizes and shapes in and about J without violating our prime assumption.

Moreover, we need to formulate boundary conditions between J and J’ and search for a contradiction to our assumption about J. It could be a limiting process or some kind of process of elimination. I am not sure what will work initially. But I have hope in our formulation of the boundary conditions between J and J’ that we shall discover the correct process or procedure and solve our problem affirmatively.. .

2 December, 2016 at 9:51 am

Anonymous

Note: We can arrange and rearrange (translate or rotate) our squares (s_1) appropriately without affecting our general Jordan Curve (J).

3 December, 2016 at 1:54 pm

Anonymous

In formulating a proof of the Inscribed Square Conjecture, we can distinguish between Jordan curves which obey our assumption (simple closed curves which does not have four points on it that form an inscribed square of any size from the unit square, s_1, to s_n less than the size of the square which inscribes it) and those which do not obey our assumption.

A Jordan curve which obeys our assumption is exceptional, and we can label it, J_e. And a Jordan curve which does not obey our assumption is regular, and we can label it, J_r.

Our task is to prove that J_e does not exist. And we can use J_r to help us prove that result. How? Hmm…

3 December, 2016 at 3:15 pm

Anonymous

Can we develop J_e from J_r?

7 December, 2016 at 2:20 pm

Anonymous

Inscribed Square Conjecture is true! The mapping all four points of the Jordan curve will eventually converge to the four corners or vertices, respectively, of a square of size, s_1, or greater.

I challenge the great Professor Tao to write the proof. He has the technical skill to do. Good luck!

7 December, 2016 at 2:25 pm

Anonymous

Oops… Correction!

I challenge the great Professor Tao to write the proof. He has the technical skill… Good luck!

10 December, 2016 at 2:41 pm

Anonymous

Reference link: https://www.researchgate.net/post/What_is_the_solution_to_the_inscribed_square_problem_Toeplitz_square_peg_problem

10 December, 2016 at 5:44 pm

Anonymous

Hmm. Is there a computer program which verifies the Inscribed Square Conjecture?

3 November, 2017 at 4:01 am

Anonymous

coulde there be a highe of

dimension generate?In general this problem is deal with multiper imtersection of a space so called “cube space generate by the curve” and the curve itself.

4 November, 2018 at 5:47 pm

Paolo Rampazzo

Well, I don’t know if you’re going to read this professor Tao, and in case you’re, I don’t know if it will make sense. But an approach I think that maybe one could try to exploit is by trying to see the problem as a linear algebra problem. Given a curve, we could select two points on this curve. The first point we can just pick a random one, and keeping it fixed, the second we can vary along the curve. Two points on the curve will define a vector. Given this vector, we could try to get its orthogonal vector. As there will be an infinite number of vectors orthogonal to the first one, we would then check the set of them which are orthogonal to the first one and for which a line on its direction would intersect the curve at least twice. If we are able to find a orthogonal vector to the first one which intersects the curve twice and whose length matches the length of the first one, then we are done. Is there any chance this would work for a general curve ? Besides the difficult of the problem itself, problems would also arise because for the first point we would have to go through “all” the points on the curve. Well, you’re the right person anyway to tackle this approach.

Best regards.

25 June, 2020 at 5:28 pm

곡선 위의 직사각형들 – Pseudorandom Things

[…] 동영상과 Zariski님의 관련글에서 이 풀이를 소개하기도 했다. 몇 년 전에는 테렌스 타오도 시도를 해서 주어진 Jordan curve가 두개의 특정한 Lipschitz curve로 나누어지는 […]