I have just uploaded to the arXiv my paper “On the number of solutions to “, submitted to the Journal of the Australian Mathematical Society.

For any positive integer , let

denote the number of solutions to the Diophantine equation

where are positive integers (we allow repetitions, and do not require the

to be increasing). The Erdös-Straus conjecture asserts that

for all

. By dividing through by any positive integer

we see that

, so it suffices to verify this conjecture for primes

, i.e. to solve the Diophantine equation

for each prime . As the case

is easily solved, we may of course restrict attention to odd primes.

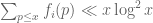

This conjecture remains open, although there is a reasonable amount of evidence towards its truth. For instance, it was shown by Vaughan that for any large , the number of exceptions

to the Erdös-Straus conjecture with

is at most

for some absolute constant

. The Erdös-Straus conjecture is also verified in several congruence classes of primes; for instance, from the identity

we see that the conjecture holds when . Further identities of this type can be used to resolve the conjecture unless

is a quadratic residue mod

, which leaves only six residue classes in that modulus to check (namely,

, and

). However, there is a significant obstruction to eliminating the quadratic residue classes, as we will discuss later.

By combining these reductions with extensive numerical calculations, the Erdös-Straus conjecture was verified for all by Swett.

One approach to solving Diophantine equations such as (1) is to use methods of analytic number theory, such as the circle method, to obtain asymptotics (or at least lower bounds) for the number of solutions (or some proxy for this number); if one obtains a lower bound which is nontrivial for every

, one has solved the problem. (One can alternatively view such methods as a variant of the probabilistic method; in this interpretation, one chooses the unknowns

according to some suitable probability distribution and then tries to show that the probability of solving the equation is positive.) Such techniques can be effective for instance for certain instances of the Waring problem. However, as a general rule, these methods only work when there are a lot of solutions, and specifically when the number

of solutions grows at a polynomial rate with the parameter

.

The first main result of my paper is that the number of solutions is essentially logarithmic in nature, thus providing a serious obstruction to solution by analytic methods, as there is almost no margin of error available. More precisely, I show that for almost all primes

(i.e. in a subset of primes of relative density

), one has

, or more precisely that

Readers familiar with analytic number theory will recognise the right-hand side from the divisor bound, which indeed plays a role in the proof.

Actually, there are more precise estimates which suggest (though do not quite prove) that the mean value of is comparable to

. To state these results properly, I need some more notation. It is not difficult to show that if

is an odd prime and

obey (1), then at least one, but not all, of the

must be a multiple of

. Thus we can split

, where

is the number of solutions to (1) where exactly

of the

are divisible by

. The sharpest estimates I can prove are then

Theorem 1 For all sufficiently large

, one has

and

Since the number of primes less than is comparable to

by the prime number theorem, this shows that the mean value of

in this range is between

and

, and the mean value of

is between

and

, which gives the previous result as a corollary (thanks to a Markov inequality argument). A naive Poisson process heuristic then suggests that each prime

has a “probability”

of having a solution to (1), which by the Borel-Cantelli lemma heuristically suggests that there are only finitely many

for which (1) fails. Of course, this is far from a rigorous proof (though the result of Vaughan mentioned earlier, which is based on the large sieve, can be viewed as a partial formalisation of the argument).

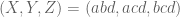

The first step in obtaining these results is an elementary description of in terms of some divisibility constraints. More precisely, we have

Lemma 2 Let

be an odd prime. Then

is equal to three times the number of triples

of positive integers, with

coprime,

dividing

, and

dividing

. Similarly,

is equal to three times the number of triples

of positive integers, with

coprime,

dividing

, and

dividing

.

One direction of this lemma is very easy: if divides

and

divides

then the identity

and its cyclic permutations give three contributions to , and similarly if

divides

instead then the identity

and its cyclic permutations give three contributions to . Conversely, some elementary number theory can be used to show that all solutions contributing to either

or

are of these forms. (Similar criteria have been used in prior literature, for instance in the previously mentioned paper of Vaughan.)

This lemma, incidentally, provides a way to quickly generate a large number of congruences of primes for which the Erdös-Straus conjecture can be verified. Indeed, from the above lemma we see that if

are coprime and

is any odd factor of

(and hence coprime to

), then the Erdös-Straus conjecture is true whenever

or

. For instance,

- Taking

, we see that the conjecture holds whenever

(leaving only those primes

);

- Taking

we see that the conjecture holds whenever

(leaving only those primes

);

- Taking

, we see that the conjecture holds whenever

((leaving only those primes

);

- Taking

, we see that the conjecture holds whenever

(leaving only those primes

);

- Taking

, we see that the conjecture holds whenever

; taking instead

, we see that the conjecture holds whenever

. (This leaves only the primes

that are equal to one of the six quadratic residues

, an observation first made by Mordell.)

- etc.

If we let (resp.

) be the number of triples

with

coprime,

dividing

, and

congruent to

(resp.

) mod

, the above lemma tells us that

for all odd primes

, so it suffices to show that

are non-zero for all

. One might hope that there are enough congruence relations provided by the previous observation to obtain a covering system of congruences which would resolve the conjecture. Unfortunately, as was also observed by Mordell, an application of the quadratic reciprocity law shows that these congruence relations cannot eliminate quadratic residues, only quadratic non-residues. More precisely, one can show that if

are as above (restricting to the case

, which contains all the unsolved cases of the conjecture) and

is the largest odd factor of

, then the Jacobi symbols

and

are always equal to

. One consequence of this is that

whenever

is an odd perfect square. This makes it quite hard to resolve the conjecture for odd primes

which resemble a perfect square in that they lie in quadratic residue classes to small moduli (and, from Dirichlet’s theorem on primes in arithmetic progressions, one can find many primes of this type). The same argument also shows that for an odd prime

, there are no solutions to

in which one or two of the are divisible by

, with the other denominators being coprime to

. (Of course, one can still get representations of

by starting with a representation of

and dividing by

, but such representations are is not of the above form.) This shows that any attempt to establish the Erdös-Straus conjecture by manually constructing

as a function of

must involve a technique which breaks down if

is replaced by

(for instance, this rules out any approach based on using polynomial combinations of

and dividing into cases based on residue classes of

in small moduli). Part of the problem here is that we do not have good bounds that prevent a prime

from “spoofing” a perfect square to all small moduli (say, to all moduli less than a small power of

); this problem is closely related (via quadratic reciprocity) to Vinogradov’s conjecture on the least quadratic nonresidue, discussed in this previous blog post.

It remains to control the sums for

. The lower bounds

are relatively routine to establish, arising from counting the contribution of those

that are somewhat small (e.g. less than

), and use only standard asymptotics of arithmetic functions and the Bombieri-Vinogradov inequality (to handle the restriction of the summation to primes). To obtain (nearly) matching upper bounds, one needs to prevent

from getting too large. In the case of

, the fact that

divides

and

divides

soon leads one to the bounds

, at which point one can count primes in residue classes modulo

with reasonable efficiency via the Brun-Titchmarsh inequality. This inequality unfortunately introduces a factor of

, which we were only able to handle by bounding it crudely by

, leading to the double logarithmic loss in the

sum.

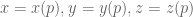

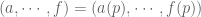

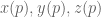

For , these arguments do not give good bounds, because it is possible for

to be much larger than

, and one can no longer easily count solutions to

. However, an elementary change of variables resolves this problem. It turns out that if one lets

be the positive integers

then one can convert the triple to a triple

obeying the constraints

Conversely, every such triple determines

by the formulae

The point is that this transformation now places in a residue class modulo

rather than

, and with

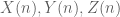

, this allows one to count the number of solutions reasonably efficiently. The main loss now comes from counting the number of divisors

of

; in particular, one becomes interested in estimating sums such as

where are less than

and

is the number of divisors of

. In principle, because

behaves like

on the average (as can be seen from the Dirichlet hyperbola method), we expect this sum to be of order

, but I was unable to show this, instead using the far cruder divisor bound

to obtain an upper bound of . Any improvement upon this bound would lead to a corresponding improvement in the upper bound for

. While improvement is possible in some ranges (particularly when

is large) using various bounds on Kloosterman-type exponential sums, I was not able to adequately control these sums when

was fairly small (e.g. polylogarithmic size in

), as one could no longer extract much of an averaging effect from the

summation in that case. Part of the difficulty is that in that case one must somehow exploit the fact that

is irreducible as a polynomial in

for any fixed

, otherwise there will be too many divisors.

— 1. Solvability criteria —

In the rest of this post, we record some sufficient conditions for an odd prime to have a solution to (1). From Lemma 2 we have already seen that we have a solution whenever we can find positive integers

with

coprime,

, and

dividing either

or

.

The representation discussed earlier gives a slightly different criterion. Indeed, we see that if

are positive integers such that

, and

, then the quantities

defined by (2) are positive integers which clearly obey

; furthermore, some algebra reveals that

and so

, and so by Lemma 2 we have a solution to (1); explicitly, we have

where . This lets us eliminate some further residue classes (restricting, as we may, to the case

):

- Taking

, we can eliminate

(or equivalently,

);

- Taking

, we can eliminate

(or equivalently,

);

- Taking

, we can eliminate

(or equivalently,

).

Unfortunately this only eliminates three of the five quadratic non-residues mod ; I do not know how to eliminate the

classes.

Here is another criterion for eliminating large numbers of primes:

Lemma 3 Let

be coprime positive integers with

odd. Suppose

is an odd prime such that

and

for some

dividing

. Then there is a positive integer solution to (1).

Proof: Write where

is square-free, then

and hence

. In particular,

divides

. As

is coprime to

and odd, it is also coprime to

.

If we then set , then we have

; also, since

and divides

, we see that

divides

, and so from Lemma 2 we have a solution to (1), more explicitly, one has

where is the positive integer

Here are some typical applications of this lemma:

Corollary 4 Let

be an odd prime. Then we have a positive integer solution to (1) whenever one of the following happens:

is divisible by a factor

.

is divisible by a factor

. (Equivalently,

is not the sum of two squares.)

- One of

,

, or

is divisible by a factor

.

- One of

,

, or

is divisible by a factor

.

- One of

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, or

is divisible by a factor

.

- One of

,

, or

is divisible by a factor

.

Proof: By previous considerations we may assume . The first claim arises from Lemma 3 with

and

. The second claim comes from taking

. The third comes from taking

and

, the fourth from

and

, and the fifth from

and

. The final claim comes from taking

and

.

These criteria already recover all the congruence relation conditions in small moduli mentioned previously, and generate infinitely many more (though again, these criteria will consistently miss all perfect squares). For instance, we may eliminate the nine residue classes

by this corollary, which is most (though not all) of the quadratic non-residue classes modulo

(omitting

and

), and similarly eliminate nine residue classes mod

, mod

, etc. (actually from

onwards we eliminate ten classes, due to the first part of the corollary).

Here is a variant of Lemma 3, adapted to the solutions rather than the

solutions:

Lemma 5 Let

be positive integers with

coprime. Suppose

is an odd prime such that

and

Then there is a positive integer solution to (1).

Proof: Write , then

is a positive integer and

. Also,

divides both

and

, so on eliminating

we see that

divides

. If

was divisible by

, then as

,

would also be divisible by

, contradicting coprimality; thus

divides

, and the claim follows from the

criterion. More explicitly, one has

Thus, for instance, restricting as before to the case , we can obtain a solution whenever one of

is divisible by some . Combining this with Corollary 4, we conclude that in order not to have a solution, we must have

for any . This unfortunately does not eliminate any more residue classes modulo

than we already had (and, of course, quadratic residues remain untouched), but eventually eliminates

classes for each sufficiently large choice of the modulus

.

Finally, we recall a criterion of Vaughan, which asserts that if there are positive integers such that

, then there is a solution to (1), namely

where . In our notation, and assuming

are coprime, this corresponds to the

representation with

(note that is also equal to

), or in the notation of Lemma 3,

(where we place tildes on the quantities in Lemma 3 to reduce confusion). Thus we see that Vaughan’s criterion is essentially the case of Lemma 2, and is basically equivalent to Lemma 3 also.

One can use these criteria to test the Erdos-Straus conjecture for all primes in a certain range, by using these sorts of tests to sieve out all but a small exceptional set of primes, which one can perhaps eliminate using a secondary, larger sieve based on the same criteria. This was done up to by Swett in 1999, using Vaughan’s criterion, which only covers the

type solutions; it is likely that with modern computers and by using criteria for both the

and

solutions, one could expand this range significantly.

39 comments

Comments feed for this article

7 July, 2011 at 2:34 pm

saltypod

Are there simple counterexamples that show that one needs to allow both $f_1$ and $f_2$ type solutions for a general $p$?

7 July, 2011 at 5:03 pm

D. Eppstein

@saltypod: if there are counterexamples, they are not tiny. I tried all primes congruent to 1 mod 4 from 5 to 197 and in each case there were solutions of both types.

7 July, 2011 at 7:42 pm

Terence Tao

It is likely (but, of course, not proven) that f_1(p) and f_2(p) are both non-zero for all odd primes p, so in principle one could restrict to just one type of solution, though this of course leads to a slightly more difficult conjecture to prove.

There is an interesting numerical coincidence that the congruences for which there are families of f_1 solutions tend to match the congruences for which there are families of f_2 solutions, which I do not fully understand the origin of (though the fact that both congruences are necessarily constrained to quadratic residues is certainly relevant), but this coincidence will probably dissipate at very large moduli. Certainly there does not appear to be a way to convert families of f_1 solutions to families of f_2 solutions or vice versa. For instance, when p=3 mod 4, there are (up to permutations) five families of f_1 solutions, namely

and

for m=1,5, but only two families of f_2 solutions, namely

and

There does not appear to be any obvious way to match up these solutions. (I plan to have a followup post detailing the precise congruences coming from the type 1 and type 2 solutions).

1 June, 2012 at 3:29 am

Stan Dolan

Dear Professor Tao, To bring some coherence to the various congruence results for f2 solutions it is interesting to consider the equation in the form Ap+B+C=4ABCD where A,B,C,D are polynomials in p. Considering degrees and results like “A divides B+C” quickly gives only two (essentially different) cases-D linear, A,B,C constant OR A,B linear, C and D constant. Very little work then gives the only possible congruence results [of this type] – and these correspond to Lemma 2 and Lemma 3, respectively. Apologies if this is already very familiar to you.

1 June, 2012 at 9:34 am

Stan Dolan

Just completed the corresponding analysis for f1. This is much more involved so I hope I have not made any errors. The good news is that this does give congruences which I do not believe are listed in the above paper. For example, let [n ] denote multiple of n and denote factor of n. Then a solution is generated for any prime of the form [4n]-<1+4>. In this particular solution, the double “factor of” helps boost the number of solutions quite effectively.

1 June, 2012 at 9:38 am

Stan Dolan

The expression <1+4> did not transmit correctly above and nor did the explanation of as meaning factor of n. Hope this works now.

1 June, 2012 at 1:47 pm

Stan Dolan

It should say

A multiple of 4n

Minus

A factor of (1 + 4 times a factor of n^2)

7 July, 2011 at 8:31 pm

Terence Tao

I’ve just learned (from Christian Elsholtz) that the results in my paper overlap to a substantial extent with some unpublished observations of Elsholtz and Heath-Brown, and by combining the two one can obtain some improvements to the results (for instance, one can remove the double logarithmic factor in the upper bound). We are now in the process of revising the paper (which is now going to become a jointly authored paper). This will of course take some time, so the version of the paper currently on the arXiv should be now treated as provisional. I'll post an update here when the revision is ready.

upper bound). We are now in the process of revising the paper (which is now going to become a jointly authored paper). This will of course take some time, so the version of the paper currently on the arXiv should be now treated as provisional. I'll post an update here when the revision is ready.

9 July, 2011 at 9:35 am

Manuel Bello-Hern\'andez

Dear Prof. Tao,

We give in {\it arXiv:1010.2035} the following decomposition

\begin{equation}\label{dec}

\frac{4}{abc-b-a}=\frac1{a\frac{bc-1}{4}}+\frac1{a(ac-1)\frac{bc-1}{m}}+ \frac1{(ac-1)\frac{bc-1}{4}(abc-b-a)},

\end{equation}

assuming $bc=1 $ mod $4$. Of course, the interesting case for Erdos-Straus conjecture is $b=3$ and $c=3$ mod $4$. The above decomposition correspond to your notation $f_1$. Using computer we have checked that for each prime $p=4q+1<10^{14}$ there exist nonnegative integer numbers $x,y,z$ such that

\[

p=(x+1)(4y+3)(4z+3)-(x+1)-(4y+3).

\]

For decomposition with two denominator divisible by $p$ (case $f_2$) we have to rewrite $p$ as $(4abc-1)d-4 b^2c$

\[

\frac4p=\frac4{(4abc-1)d-4 b^2c}=\frac1{abcp}+\frac1{bc(ad-b)}+\frac1{ac(ad-b)p}

\]

We have checked that all prime $p=4q+1<10^{10}$ can be written as $(4abc-1)d-4 b^2c$ with $d=1$ mod 4.

Best regards, Manuel Bello-Hern\'andez.

8 July, 2011 at 5:27 am

Stones Cry Out - If they keep silent… » Things Heard: e180v5

[…] Well, to be honest I’m mostly linking this so I don’t lose it and can go back to it. […]

11 July, 2011 at 7:31 am

Terence Tao

A brief update: Christian Elsholtz and I have managed to obtain the right upper bound for both i=1 and i=2 now (thus eliminating the various losses in the version of the paper currently on the arXiv), by adapting an old argument of Erdos. We’ll put up the updated version of the ms (which now also contains a number of other related results as well) when it is fully written up and ready for resubmission, of course.

for both i=1 and i=2 now (thus eliminating the various losses in the version of the paper currently on the arXiv), by adapting an old argument of Erdos. We’ll put up the updated version of the ms (which now also contains a number of other related results as well) when it is fully written up and ready for resubmission, of course.

I’ll keep updating the situation as it develops, of course.

15 July, 2011 at 6:23 pm

cadet

I have a few clarifications/corrections in the paper.

p. 8, first equation in that page: Have you got the roles of $i$ and $j$ flipped in a few places? Specifically, $k \ll 2^j$ and the number of choices of $(a,b)$ is $2^i$, right?

p. 9, first equation in the page: Did you mean to say $\phi(a) \gg a / log log a$? Of course, the equation is correct as it stands..

In p. 11, Equation 23: Should the right hand side be $x (log x)^2$ instead of $x^2 log x$?

[Thanks! Actually the paper is being revised substantially for other reasons, I hope to have a new version up in the near future. -T.]

23 July, 2011 at 7:41 pm

Erdos’ divisor bound « What’s new

[…] original paper of Erdös was also corrected in this latter paper.) In a forthcoming revision to my paper on the Erdös-Straus conjecture, Christian Elsholtz and I have also applied this method to obtain bounds such […]

31 July, 2011 at 10:17 pm

Counting the number of solutions to the Erdös-Straus equation on unit fractions « What’s new

[…] submitted to the Journal of the Australian Mathematical Society. This supercedes my previous paper on the subject, by obtaining stronger and more general results. (The paper is currently in the process of being […]

20 September, 2011 at 2:47 am

Diophantine sets and the integers | cartesian product

[…] On the number of solutions to 4/p = 1/n_1 + 1/n_2 + 1/n_3 (terrytao.wordpress.com) […]

12 June, 2012 at 5:38 am

Stan Dolan

Numbers of the form 4abc-(a+b)/d, with all variables positive integers, seem interesting in their own right. A reciprocity argument can be used to prove that none are squares (either even or odd). Does anyone know of other classes of number that cannot be so expressed?

9 April, 2012 at 12:12 pm

Ibrahima GUEYE

Dear all

The Professor MIZONY and me do rcent progress about the Erdös-Straus conjecture.

We will publish it icA

18 April, 2012 at 5:30 pm

ibrahimaeygue

Dear all. Please go to Professor MINOZY’s web page and see the relation between Erdös-Straus conjecture and twin Pythagorians triples

28 April, 2012 at 5:49 pm

ibrahimaeygue

Dear all

Here you are the link

Click to access Recent%20progress%20about%20Erdos-Straus%20conjecture.pdf

Best regards

29 May, 2012 at 5:46 am

Stan Dolan

Dear Professor Tao

Regarding quadratic residues section –

a=2, b=7, c=3, p=53. Then q=7 but -3 is a q.r. for 7.

What have I misunderstood?

Many thanks

29 May, 2012 at 8:27 am

Terence Tao

Oops, I forgot to add the restriction to that claim, which is needed for the quadratic reciprocity argument to work correctly. (But the

to that claim, which is needed for the quadratic reciprocity argument to work correctly. (But the  class covers all the open cases of the conjecture, as already discussed in the post.)

class covers all the open cases of the conjecture, as already discussed in the post.)

29 May, 2012 at 10:49 am

Stan Dolan

Many thanks for your very helpful reply. I suppose I should have realized. With your hint re p, the proof is straightforward but nevertheless it is a brilliant example of quadratic reciprocity which deserves to be better known. Best wishes.

29 May, 2012 at 3:45 pm

Stan Dolan

An odd prime p has an f2 solution if and only if there are positive integers a, b and c such that p=a(4b-1)-b^2/c.

This observation probably does not contribute anything new to the theory but is quite a neat way of characterising solutions.

29 May, 2012 at 4:27 pm

Stan Dolan

Oops – missed out a factor of 4 viz

p=a(4b-1)-4*b^2/c.

29 May, 2012 at 7:26 am

Ibrahim Gueye

Dear all

Please dread this link http://math.univ-lyon1.fr/~mizony/Towards%20the%20proof%20of%20Erdos-Straus%20conjecture.pdf

Best regards

7 March, 2013 at 5:21 pm

ibrahimaeyguebrahima GUEYE

Dear Professor TAO

Recently Professor MIZONY and me published articles about Erdös-Straus conjecture. We show the relation between this conjecture and the Pythagorean triples. Can you read them please?

Click to access 1339390041YES%202.pdf

Click to access 1339408468YES%2014.pdf

You can too read this paper :

Click to access SurErdos_Straus2.pdf

Best regards

10 January, 2014 at 9:52 am

Koussay

Bonsoir!

Solution dans la moitié des cas!,

1/N + +1/(N/2) + 1/N = 4/N , lorsque N est divisinle par 2 !,(N est paire)

11 January, 2015 at 3:50 am

Koussay

Bonjour!

En fait je travaille sur cette conjecture dépuis 2 ans, la dérniere nouveauté concernant ca, était la résolution pour tous les termes de toutes les suite suivantes:

( 3n – 1 ) , ( 7n – 2 ) , ( 11n – 3 ) , …..etc…

please veuillez-vous voir ca:

https://fr.answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20150110031531AA7Jsn3

Est ce que c’est importante, ou bien c’est triviale ?

merci, pour mettre votre avis s.V.P ?

19 January, 2015 at 3:06 am

Koussayj

Je remplace le lien suivant:

https://fr.answers.yahoo.com/activity/questions

Au lieu de l’ancien:

https://fr.answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20150110031531AA7Jsn3

11 January, 2015 at 4:04 am

Koussay

Concernant la conjecture d’Erdos-Strauss: 1/a + 1/b + 1/c = 4/N , alors:

1- Si le N est un multiple de 3,(( c-a-d: N est de la forme: N = 3n)), la résolution c’est:

1/(4N/3) + 1/(N/3) + 1/(4N) = 4/N

2- Si le N est de la forme : N = 3n-1, la résolution c’est:

1/n + 1/(3n-1) + 1/[ n(3n-1) ] = 4/(3n-1),

Il reste donc, la résolution dans le cas où: le N est de la forme suivante:

N = 3n+1 , mais:

En plus la résolution lorsque N est paire, c’est:

1/N + 1/(N/2) + 1/N = 4/N , donc il reste la résolution lorsque N est de la forme suivante: N = 6n + 1

Est-ce que c’est interessant, ou bien c’est triviale selon vous ?

Merci pour vos avis

23 February, 2018 at 5:20 am

Jose Manuel Montolio Aranda

Good way.

I solved all the other cases.

“Comentarios en Teoría de Números”

en safecreative.org, openthesis.org

Saludos!

José Manuel Montolio Aranda

SPAIN

jmmaranda@hispavista.com

19 January, 2015 at 3:18 am

Koussay

La résolution lorsque KN accepte la division sur 3K – 1, c’est:

1/(KN) + 1/[ KN/(3K – 1) ] + 1/N = 4/N

tel que Le “K” est de notre choit!

@@@ Translation en English By Google:

The resolution when KN accept the division of 3K – 1 is:

1/(KN) + 1/[ KN/(3K – 1) ] + 1/N = 4/N

where the “K” is our choice!

31 March, 2015 at 3:16 pm

Marcelo

Hey all,

I’m an undergraduate student and a big fan of T. T. (congratulations on another outstanding post! :) ).

I think I have recently proved a result similar to lemma 5, which at first sight seems to be one of its particular case, but it’s not. It is:

Let equal 1 or 2 and

equal 1 or 2 and  be positive integers with

be positive integers with  coprime and

coprime and  . Suppose

. Suppose  is an odd prime such that

is an odd prime such that

and

Then there is a positive integer solution.

I was thinking of publishing a note with its proof but I don't know if this is enough. Does anyone think that this is not enough to publish?

If anyone could tell me whether this result is a trivial consequence of a combination of the ones in this post (or of any other one may find) I would very much appreciate it.

Thanks!

31 March, 2015 at 4:01 pm

Terence Tao

Relabeling your divisibility criteria as and

and  , or equivalently as

, or equivalently as  and

and  , this follows from Proposition 2.6 of the latest version of the paper (http://arxiv.org/pdf/1107.1010v5.pdf), or more precisely the remarks just preceding that proposition.

, this follows from Proposition 2.6 of the latest version of the paper (http://arxiv.org/pdf/1107.1010v5.pdf), or more precisely the remarks just preceding that proposition.

30 July, 2015 at 2:27 pm

Serge E. Salez

Dear professor Tao

I should like to have some explanation about a proof you give in your paper arxiv 1107.1010v5 (section 10). It’s well known that an odd prime number verify the conjecture of Erdos-Straus

verify the conjecture of Erdos-Straus

if and only if there exist four positive integers, say such that one of the two equations holds

such that one of the two equations holds

This necessary and sufficient condition may easily be extended to the case where is the polynomial

is the polynomial  (with

(with  ) and

) and  are polynomials of

are polynomials of ![\mathbb{Z}[t]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbb%7BZ%7D%5Bt%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) whose leading coefficients are positive integers because

whose leading coefficients are positive integers because ![\mathbb{Z}[t]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbb%7BZ%7D%5Bt%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) is factorial. In your paper, you extend that to a more general case, namely where

is factorial. In your paper, you extend that to a more general case, namely where  are in

are in  that is are

that is are

integer-valued polynomials. It’s obvious that the condition is still sufficient. My question concern the necessity. You say:

for all sufficiently large primes in this class, where

in this class, where  are polynomials of

are polynomials of  that take natural number values for all large

that take natural number values for all large  in this class. For all sufficiently large

in this class. For all sufficiently large  , we either have

, we either have  for all

for all  , or

, or  for all

for all  ; by symmetry we may assume the latter. Applying Proposition 2.2, we see that

; by symmetry we may assume the latter. Applying Proposition 2.2, we see that

for some -point

-point  in

in  with

with  having no common factor. In particular,

having no common factor. In particular,  ) is the least common multiple [I assume you meant GCD] of

) is the least common multiple [I assume you meant GCD] of  .”

.”

and

I’ll try to show my problem on an example. I take and

and  . Let

. Let  . We see that

. We see that

and that take positive integer values when

take positive integer values when  is positive.

is positive.

and . On more

. On more  never gives integer values.

never gives integer values.

So, the polynomials are defined as above but up to a multiplicative constant in

are defined as above but up to a multiplicative constant in  . In this example, the solution of

. In this example, the solution of  can be easily found:

can be easily found:

We see that these polynomials give integer values when . It is not obvious that this can be done for each example and I don’t see how to prove it in the general case.

. It is not obvious that this can be done for each example and I don’t see how to prove it in the general case.

Best.

30 July, 2015 at 7:40 pm

Terence Tao

You’re right, there are some issues here due to the discrepancy between greatest common divisors in![{\mathbf Q}[t]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Cmathbf+Q%7D%5Bt%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) and

and ![{\mathbf Z}[t]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Cmathbf+Z%7D%5Bt%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) . After accounting for this discrepancy, what seems to be happening is this: the gcd

. After accounting for this discrepancy, what seems to be happening is this: the gcd  is not quite a polynomial function on

is not quite a polynomial function on  , but is instead “piecewise polynomial” in the following sense: one can partition the original residue class into finitely many subclasses, such that on each such class,

, but is instead “piecewise polynomial” in the following sense: one can partition the original residue class into finitely many subclasses, such that on each such class,  is polynomial (in fact this polynomial is always a scalar multiple of the gcd of

is polynomial (in fact this polynomial is always a scalar multiple of the gcd of  in

in ![{\mathbf Q}[t]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5Cmathbf+Q%7D%5Bt%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) , but the choice of scalar depends on the subclass). Similarly for the other functions

, but the choice of scalar depends on the subclass). Similarly for the other functions  . The upshot is that the statement of Theorem 1.9 needs to be changed slightly; a primitive residue class that can be solved by polynomials might not be completely contained in just one of the residue classes in the indicated families, but it can always be covered by a finite number of such classes. (One could probably, with a bit more computation, work out exactly which finite unions of classes in the indicated families can be solved using a single polynomial; probably this is a very rare situation, due to some coincidences amongst the polynomials associated to each residue class.)

. The upshot is that the statement of Theorem 1.9 needs to be changed slightly; a primitive residue class that can be solved by polynomials might not be completely contained in just one of the residue classes in the indicated families, but it can always be covered by a finite number of such classes. (One could probably, with a bit more computation, work out exactly which finite unions of classes in the indicated families can be solved using a single polynomial; probably this is a very rare situation, due to some coincidences amongst the polynomials associated to each residue class.)

We’ll get this fixed in the arXiv version of the paper soon. Thanks for pointing out the issue.

23 February, 2018 at 5:30 am

Jose Manuel Montolio Aranda

Well, Mr.Tao.

I solved the conjecture.

José Manuel Montolio Aranda

ESPAÑA

“Comentarios en Teoría de Números”

http://www.safecreative.org, http://www.openthesis.org.

23 February, 2018 at 5:50 am

Jose Manuel Montolio Aranda

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Teorema

La ec. Straüss-Erdös: 4/n =1/a + 1/b + 1/c.(n>1).

Es equivalente a:

Para todo n, existen un “m”, y un “k”, enteros,

tal que tres divisores de “n*m”, suman “4*k*m”.

Demostración

Sean A,B,C los tres divisores de nm. Con nm=aA=bB=cC

Para k=1, 4/n =(4m/nm) =(A+B+C)/nm =(1/a)+(1/b)+(1/c)

Para k>1, A+B+C=4km, a=(nm/A)k,b=(nm/B)k,c=(nm/C)k.

Straüss-Erdös. Ejemplo de solución

——————————————————

n 2 m 1 nm 2 4m= 1+ 1+ 2 (a 2 b 2 c 1)

n 3 m 2 nm 6 4m= 1+ 1+ 6 (a 6 b 6 c 1)

n 4 m 1 nm 4 4m= 1+ 1+ 2 (a 4 b 4 c 2)

n 5 m 2 nm 10 4m= 1+ 2+ 5 (a 10 b 5 c 2)

n 7 m 4 nm 28 4m= 1+ 1+ 14 (a 28 b 28 c 2)

Teorema

Si m soluciona a cierto nro.primo p,entonces m soluciona a todo N con factor menor p.

La demostración es obvia.

Ejemplo. Se omite k=1.

N 4m A B C ( a b c)

———————————————

p=7 4*4= 16 = 7 +7 +2 4/n =( 4 4 2n)

49 4*4= 16 = 7 +7 +2 4/n =( 28 28 2n)

77 4*4= 16 = 7 +7 +2 4/n =( 44 44 2n)

91 4*4= 16 = 7 +7 +2 4/n =( 52 52 2n)

119 4*4= 16 = 7 +7 +2 4/n =( 68 68 2n)

———————————————

Serie aritmética solucionable

Diremos que una serie aritmética “n=A+Bw” tiene solución, si existe una expresión explícita y constante de n, que da la terna de valores (a,b,c) para todo nro. de la serie.

Ejemplo

n= A+Bw ( a , b , c )

—————————————————–

0+2w ( n ,n ,n/2 )

2+3w ( (n+1)/3 ,n(n+1)/3 ,n )

3+4w ( (n+1)/4 ,n(n+1)/4 ,- )

5+8w ( (n+3)/4 ,(n/2)*(n+3)/4 ,n(n+3)/4 )

——————————————-

Estas cuatro series recubren por si sólas a todo valor entero,

excepto por los nros. “1+24w”.

Si n es nro. compuesto, tiene una solución dada por su factor primo menor.

Si n pertenece a una serie ya solucionada, tendrá la sol. correspondiente.

Teorema

Todo nro. primo n, inicia una serie con solución. En dicha serie, m es constante y k secuencial. Los valores A,B,C mantienen una expresion constante.

Ejemplo. Serie Aritmética 5+8w

n k m A B C a b c

——————————————————

PR 5 4* 1* 2= 8 =[ 1n 2 1] 4/n =( 2 1n 2n)

PR 13 4* 2* 2= 16 =[ 1n 2 1] 4/n =( 4 2n 4n)

PR 157 4*20* 2= 160 =[ 1n 2 1] 4/n =( 40 20n 40n)

——————————————————-

Ejemplo de serie que inicia un nro. primo

PR 3 4* 1* 2= 8 =[ 1n 1n 2]; 4/n =( 2 2 1n);S.Aritmética 3+ 4n

PR 5 4* 1* 2= 8 =[ 1n 2 1]; 4/n =( 2 1n 2n);S.Aritmética 5+ 8n

PR 7 4* 2* 2= 16 =[ 1n 1n 2]; 4/n =( 4 4 2n);S.Aritmética 7+ 8n

PR 11 4* 3* 2= 24 =[ 1n 1n 2]; 4/n =( 6 6 3n);S.Aritmética 11+12n

PR 13 4* 2* 2= 16 =[ 1n 2 1]; 4/n =( 4 2n 4n);S.Aritmética 13+16n

PR 17 4* 1* 6= 24 =[ 1n 6 1]; 4/n =( 6 1n 6n);S.Aritmética 17+24n

from my work Comentarios.

JM Montolio A.

ESPAÑA

23 February, 2018 at 5:51 am

Jose Manuel Montolio Aranda

jmmaranda@hispavista.com

Jose Manuel Montolio Aranda