You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Cayley graphs’ tag.

The wave equation is usually expressed in the form

where is a function of both time

and space

, with

being the Laplacian operator. One can generalise this equation in a number of ways, for instance by replacing the spatial domain

with some other manifold and replacing the Laplacian

with the Laplace-Beltrami operator or adding lower order terms (such as a potential, or a coupling with a magnetic field). But for sake of discussion let us work with the classical wave equation on

. We will work formally in this post, being unconcerned with issues of convergence, justifying interchange of integrals, derivatives, or limits, etc.. One then has a conserved energy

which we can rewrite using integration by parts and the inner product

on

as

A key feature of the wave equation is finite speed of propagation: if, at time (say), the initial position

and initial velocity

are both supported in a ball

, then at any later time

, the position

and velocity

are supported in the larger ball

. This can be seen for instance (formally, at least) by inspecting the exterior energy

and observing (after some integration by parts and differentiation under the integral sign) that it is non-increasing in time, non-negative, and vanishing at time .

The wave equation is second order in time, but one can turn it into a first order system by working with the pair rather than just the single field

, where

is the velocity field. The system is then

and the conserved energy is now

Finite speed of propagation then tells us that if are both supported on

, then

are supported on

for all

. One also has time reversal symmetry: if

is a solution, then

is a solution also, thus for instance one can establish an analogue of finite speed of propagation for negative times

using this symmetry.

If one has an eigenfunction

of the Laplacian, then we have the explicit solutions

of the wave equation, which formally can be used to construct all other solutions via the principle of superposition.

When one has vanishing initial velocity , the solution

is given via functional calculus by

and the propagator can be expressed as the average of half-wave operators:

One can view as a minor of the full wave propagator

which is unitary with respect to the energy form (1), and is the fundamental solution to the wave equation in the sense that

Viewing the contraction as a minor of a unitary operator is an instance of the “dilation trick“.

It turns out (as I learned from Yuval Peres) that there is a useful discrete analogue of the wave equation (and of all of the above facts), in which the time variable now lives on the integers

rather than on

, and the spatial domain can be replaced by discrete domains also (such as graphs). Formally, the system is now of the form

where is now an integer,

take values in some Hilbert space (e.g.

functions on a graph

), and

is some operator on that Hilbert space (which in applications will usually be a self-adjoint contraction). To connect this with the classical wave equation, let us first consider a rescaling of this system

where is a small parameter (representing the discretised time step),

now takes values in the integer multiples

of

, and

is the wave propagator operator

or the heat propagator

(the two operators are different, but agree to fourth order in

). One can then formally verify that the wave equation emerges from this rescaled system in the limit

. (Thus,

is not exactly the direct analogue of the Laplacian

, but can be viewed as something like

in the case of small

, or

if we are not rescaling to the small

case. The operator

is sometimes known as the diffusion operator)

Assuming is self-adjoint, solutions to the system (3) formally conserve the energy

This energy is positive semi-definite if is a contraction. We have the same time reversal symmetry as before: if

solves the system (3), then so does

. If one has an eigenfunction

to the operator , then one has an explicit solution

to (3), and (in principle at least) this generates all other solutions via the principle of superposition.

Finite speed of propagation is a lot easier in the discrete setting, though one has to offset the support of the “velocity” field by one unit. Suppose we know that

has unit speed in the sense that whenever

is supported in a ball

, then

is supported in the ball

. Then an easy induction shows that if

are supported in

respectively, then

are supported in

.

The fundamental solution to the discretised wave equation (3), in the sense of (2), is given by the formula

where and

are the Chebyshev polynomials of the first and second kind, thus

and

In particular, is now a minor of

, and can also be viewed as an average of

with its inverse

:

As before, is unitary with respect to the energy form (4), so this is another instance of the dilation trick in action. The powers

and

are discrete analogues of the heat propagators

and wave propagators

respectively.

One nice application of all this formalism, which I learned from Yuval Peres, is the Varopoulos-Carne inequality:

Theorem 1 (Varopoulos-Carne inequality) Let

be a (possibly infinite) regular graph, let

, and let

be vertices in

. Then the probability that the simple random walk at

lands at

at time

is at most

, where

is the graph distance.

This general inequality is quite sharp, as one can see using the standard Cayley graph on the integers . Very roughly speaking, it asserts that on a regular graph of reasonably controlled growth (e.g. polynomial growth), random walks of length

concentrate on the ball of radius

or so centred at the origin of the random walk.

Proof: Let be the graph Laplacian, thus

for any , where

is the degree of the regular graph and sum is over the

vertices

that are adjacent to

. This is a contraction of unit speed, and the probability that the random walk at

lands at

at time

is

where are the Dirac deltas at

. Using (5), we can rewrite this as

where we are now using the energy form (4). We can write

where is the simple random walk of length

on the integers, that is to say

where

are independent uniform Bernoulli signs. Thus we wish to show that

By finite speed of propagation, the inner product here vanishes if . For

we can use Cauchy-Schwarz and the unitary nature of

to bound the inner product by

. Thus the left-hand side may be upper bounded by

and the claim now follows from the Chernoff inequality.

This inequality has many applications, particularly with regards to relating the entropy, mixing time, and concentration of random walks with volume growth of balls; see this text of Lyons and Peres for some examples.

For sake of comparison, here is a continuous counterpart to the Varopoulos-Carne inequality:

Theorem 2 (Continuous Varopoulos-Carne inequality) Let

, and let

be supported on compact sets

respectively. Then

where

is the Euclidean distance between

and

.

Proof: By Fourier inversion one has

for any real , and thus

By finite speed of propagation, the inner product vanishes when

; otherwise, we can use Cauchy-Schwarz and the contractive nature of

to bound this inner product by

. Thus

Bounding by

, we obtain the claim.

Observe that the argument is quite general and can be applied for instance to other Riemannian manifolds than .

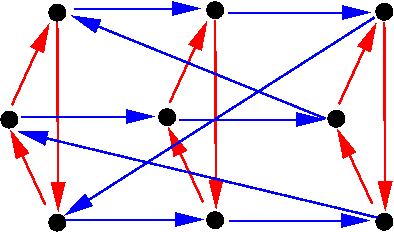

This is a sequel to my previous blog post “Cayley graphs and the geometry of groups“. In that post, the concept of a Cayley graph of a group was used to place some geometry on that group

. In this post, we explore a variant of that theme, in which (fragments of) a Cayley graph on

is used to describe the basic algebraic structure of

, and in particular on elementary word identities in

. Readers who are familiar with either category theory or group homology/cohomology will recognise these concepts lurking not far beneath the surface; we wil remark briefly on these connections later in this post. However, no knowledge of categories or cohomology is needed for the main discussion, which is primarily focused on elementary group theory.

Throughout this post, we fix a single group , which is allowed to be non-abelian and/or infinite. All our graphs will be directed, with loops and multiple edges permitted.

In the previous post, we drew the entire Cayley graph of a group . Here, we will be working much more locally, and will only draw the portions of the Cayley graph that are relevant to the discussion. In this graph, the vertices are elements

of the group

, and one draws a directed edge from

to

labeled (or “coloured”) by the group element

for any

; the graph consisting of all such vertices and edges will be denoted

. Thus, a typical edge in

looks like this:

Figure 1.

One usually does not work with the complete Cayley graph . It is customary to instead work with smaller Cayley graphs

, in which the edge colours

are restricted to a smaller subset of

, such as a set of generators for

. As we will be working locally, we will in fact work with even smaller fragments of

at a time; in particular, we only use a handful of colours (no more than nine, in fact, for any given diagram), and we will not require these colours to generate the entire group (we do not care if the Cayley graph is connected or not, as this is a global property rather than a local one).

Cayley graphs are left-invariant: for any , the left translation map

is a graph isomorphism. To emphasise this left invariance, we will usually omit the vertex labels, and leave only the coloured directed edge, like so:

Figure 2.

This is analogous to how, in undergraduate mathematics and physics, vectors in Euclidean space are often depicted as arrows of a given magnitude and direction, with the initial and final points of this arrow being of secondary importance only. (Indeed, this depiction of vectors in a vector space can be viewed as an abelian special case of the more general depiction of group elements used in this post.)

Let us define a diagram to be a finite directed graph , with edges coloured by elements of

, which has at least one graph homomorphism into the complete Cayley graph

of

; thus there exists a map

(not necessarily injective) with the property that

whenever

is a directed edge in

coloured by a group element

. Informally, a diagram is a finite subgraph of a Cayley graph with the vertex labels omitted, and with distinct vertices permitted to represent the same group element. Thus, for instance, the single directed edge displayed in Figure 2 is a very simple example of a diagram. An even simpler example of a diagram would be a depiction of the identity element:

We will however omit the identity loops in our diagrams in order to reduce clutter.

We make the obvious remark that any directed edge in a diagram can be coloured by at most one group element , since

implies

. This simple observation provides a way to prove group theoretic identities using diagrams: to show that two group elements

are equal, it suffices to show that they connect together (with the same orientation) the same pair of vertices in a diagram.

Remark 1 One can also interpret these diagrams as commutative diagrams in a category in which all the objects are copies of

, and the morphisms are right-translation maps. However, we will deviate somewhat from the category theoretic way of thinking here by focusing on the geometric arrangement and shape of these diagrams, rather than on their abstract combinatorial description. In particular, we view the arrows more as distorted analogues of vector arrows, than as the abstract arrows appearing in category theory.

Just as vector addition can be expressed via concatenation of arrows, group multiplication can be described by concatenation of directed edges. Indeed, for any , the vertices

can be connected by the following triangular diagram:

In a similar spirit, inversion is described by the following diagram:

Figure 5.

We make the pedantic remark though that we do not consider a edge to be the reversal of the

edge, but rather as a distinct edge that just happens to have the same initial and final endpoints as the reversal of the

edge. (This will be of minor importance later, when we start integrating “

-forms” on such edges.)

A fundamental operation for us will be that of gluing two diagrams together.

Lemma 1 ((Labeled) gluing) Let

be two diagrams of a given group

. Suppose that the intersection

of the two diagrams connects all of

(i.e. any two elements of

are joined by a path in

). Then the union

is also a diagram of

.

Proof: By hypothesis, we have graph homomorphisms ,

. If they agree on

then one simply glues together the two homomorphisms to create a new graph homomorphism

. If they do not agree, one can apply a left translation to either

or

to make the two diagrams agree on at least one vertex of

; then by the connected nature of

we see that they now must agree on all vertices of

, and then we can form the glued graph homomorphism as before.

The above lemma required one to specify the label the vertices of (in order to form the intersection

and union

). However, if one is presented with two diagrams

with unlabeled vertices, one can identify some partial set of vertices of

with a partial set of vertices of

of matching cardinality. Provided that the subdiagram common to

and

after this identification connects all of the common vertices together, we may use the above lemma to create a glued diagram

.

For instance, if a diagram contains two of the three edges in the triangular diagram in Figure 4, one can “fill in” the triangle by gluing in the third edge:

Figure 6.

One can use glued diagrams to demonstrate various basic group-theoretic identities. For instance, by gluing together two copies of the triangular diagram in Figure 4 to create the glued diagram

Figure 7.

and then filling in two more triangles, we obtain a tetrahedral diagram that demonstrates the associative law :

Figure 8.

Similarly, by gluing together two copies of Figure 4 with three copies of Figure 5 in an appropriate order, we can demonstrate the Abel identity :

Figure 9.

In addition to gluing, we will also use the trivial operation of erasing: if is a diagram for a group

, then any subgraph of

(formed by removing vertices and/or edges) is also a diagram of

. This operation is not strictly necessary for our applications, but serves to reduce clutter in the pictures.

If two group elements commute, then we obtain a parallelogram as a diagram, exactly as in the vector space case:

Figure 10.

In general, of course, two arbitrary group elements will fail to commute, and so this parallelogram is no longer available. However, various substitutes for this diagram exist. For instance, if we introduce the conjugate

of one group element

by another, then we have the following slightly distorted parallelogram:

Figure 11.

By appropriate gluing and filling, this can be used to demonstrate the homomorphism properties of a conjugation map :

Figure 12.

Figure 13.

Another way to replace the parallelogram in Figure 10 is to introduce the commutator of two elements, in which case we can perturb the parallelogram into a pentagon:

Figure 14.

We will tend to depict commutator edges as being somewhat shorter than the edges generating that commutator, reflecting a “perturbative” or “nilpotent” philosophy. (Of course, to fully reflect a nilpotent perspective, one should orient commutator edges in a different dimension from their generating edges, but of course the diagrams drawn here do not have enough dimensions to display this perspective easily.) We will also be adopting a “Lie” perspective of interpreting groups as behaving like perturbations of vector spaces, in particular by trying to draw all edges of the same colour as being approximately (though not perfectly) parallel to each other (and with approximately the same length).

Gluing the above pentagon with the conjugation parallelogram and erasing some edges, we discover a “commutator-conjugate” triangle, describing the basic identity :

Figure 15.

Other gluings can also give the basic relations between commutators and conjugates. For instance, by gluing the pentagon in Figure 14 with its reflection, we see that . The following diagram, obtained by gluing together copies of Figures 11 and 15, demonstrates that

,

Figure 16.

while this figure demonstrates that :

Figure 17.

Now we turn to a more sophisticated identity, the Hall-Witt identity

which is the fully noncommutative version of the more well-known Jacobi identity for Lie algebras.

The full diagram for the Hall-Witt identity resembles a slightly truncated parallelopiped. Drawing this truncated paralleopiped in full would result in a rather complicated looking diagram, so I will instead display three components of this diagram separately, and leave it to the reader to mentally glue these three components back to form the full parallelopiped. The first component of the diagram is formed by gluing together three pentagons from Figure 14, and looks like this:

This should be thought of as the “back” of the truncated parallelopiped needed to establish the Hall-Witt identity.

While it is not needed for proving the Hall-Witt identity, we also observe for future reference that we may also glue in some distorted parallelograms and obtain a slightly more complicated diagram:

Figure 19.

To form the second component, let us now erase all interior components of Figure 18 or Figure 19:

Figure 20.

Then we fill in three distorted parallelograms:

Figure 21.

This is the second component, and is the “front” of the truncated praallelopiped, minus the portions exposed by the truncation.

Finally, we turn to the third component. We begin by erasing the outer edges from the second component in Figure 21:

Figure 22.

We glue in three copies of the commutator-conjugate triangle from Figure 15:

Figure 23.

But now we observe that we can fill in three pentagons, and obtain a small triangle with edges :

Figure 24.

Erasing everything except this triangle gives the Hall-Witt identity. Alternatively, one can glue together Figures 18, 21, and 24 to obtain a truncated parallelopiped which one can view as a geometric representation of the proof of the Hall-Witt identity.

Among other things, I found these diagrams to be useful to visualise group cohomology; I give a simple example of this below, developing an analogue of the Hall-Witt identity for -cocycles.

In the previous set of notes we introduced the notion of expansion in arbitrary -regular graphs. For the rest of the course, we will now focus attention primarily to a special type of

-regular graph, namely a Cayley graph.

Definition 1 (Cayley graph) Let

be a group, and let

be a finite subset of

. We assume that

is symmetric (thus

whenever

) and does not contain the identity

(this is to avoid loops). Then the (right-invariant) Cayley graph

is defined to be the graph with vertex set

and edge set

, thus each vertex

is connected to the

elements

for

, and so

is a

-regular graph.

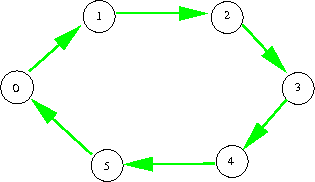

Example 2 The graph in Exercise 3 of Notes 1 is the Cayley graph on

with generators

.

Remark 3 We call the above Cayley graphs right-invariant because every right translation

on

is a graph automorphism of

. This group of automorphisms acts transitively on the vertex set of the Cayley graph. One can thus view a Cayley graph as a homogeneous space of

, as it “looks the same” from every vertex. One could of course also consider left-invariant Cayley graphs, in which

is connected to

rather than

. However, the two such graphs are isomorphic using the inverse map

, so we may without loss of generality restrict our attention throughout to left Cayley graphs.

Remark 4 For minor technical reasons, it will be convenient later on to allow

to contain the identity and to come with multiplicity (i.e. it will be a multiset rather than a set). If one does so, of course, the resulting Cayley graph will now contain some loops and multiple edges.

For the purposes of building expander families, we would of course want the underlying groupto be finite. However, it will be convenient at various times to “lift” a finite Cayley graph up to an infinite one, and so we permit

to be infinite in our definition of a Cayley graph.

We will also sometimes consider a generalisation of a Cayley graph, known as a Schreier graph:

Definition 5 (Schreier graph) Let

be a finite group that acts (on the left) on a space

, thus there is a map

from

to

such that

and

for all

and

. Let

be a symmetric subset of

which acts freely on

in the sense that

for all

and

, and

for all distinct

and

. Then the Schreier graph

is defined to be the graph with vertex set

and edge set

.

Example 6 Every Cayley graph

is also a Schreier graph

, using the obvious left-action of

on itself. The

-regular graphs formed from

permutations

that were studied in the previous set of notes is also a Schreier graph provided that

for all distinct

, with the underlying group being the permutation group

(which acts on the vertex set

in the obvious manner), and

.

Exercise 7 If

is an even integer, show that every

-regular graph is a Schreier graph involving a set

of generators of cardinality

. (Hint: you may assume without proof Petersen’s 2-factor theorem, which asserts that every

-regular graph with

even can be decomposed into

edge-disjoint

-regular graphs. Now use the previous example.)

We return now to Cayley graphs. It is easy to characterise qualitative expansion properties of Cayley graphs:

Exercise 8 (Qualitative expansion) Let

be a finite Cayley graph.

- (i) Show that

is a one-sided

-expander for

for some

if and only if

generates

.

- (ii) Show that

is a two-sided

-expander for

for some

if and only if

generates

, and furthermore

intersects each index

subgroup of

.

We will however be interested in more quantitative expansion properties, in which the expansion constant is independent of the size of the Cayley graph, so that one can construct non-trivial expander families

of Cayley graphs.

One can analyse the expansion of Cayley graphs in a number of ways. For instance, by taking the edge expansion viewpoint, one can study Cayley graphs combinatorially, using the product set operation

of subsets of .

Exercise 9 (Combinatorial description of expansion) Let

be a family of finite

-regular Cayley graphs. Show that

is a one-sided expander family if and only if there is a constant

independent of

such that

for all sufficiently large

and all subsets

of

with

.

One can also give a combinatorial description of two-sided expansion, but it is more complicated and we will not use it here.

Exercise 10 (Abelian groups do not expand) Let

be a family of finite

-regular Cayley graphs, with the

all abelian, and the

generating

. Show that

are a one-sided expander family if and only if the Cayley graphs have bounded cardinality (i.e.

). (Hint: assume for contradiction that

is a one-sided expander family with

, and show by two different arguments that

grows at least exponentially in

and also at most polynomially in

, giving the desired contradiction.)

The left-invariant nature of Cayley graphs also suggests that such graphs can be profitably analysed using some sort of Fourier analysis; as the underlying symmetry group is not necessarily abelian, one should use the Fourier analysis of non-abelian groups, which is better known as (unitary) representation theory. The Fourier-analytic nature of Cayley graphs can be highlighted by recalling the operation of convolution of two functions , defined by the formula

This convolution operation is bilinear and associative (at least when one imposes a suitable decay condition on the functions, such as compact support), but is not commutative unless is abelian. (If one is more algebraically minded, one can also identify

(when

is finite, at least) with the group algebra

, in which case convolution is simply the multiplication operation in this algebra.) The adjacency operator

on a Cayley graph

can then be viewed as a convolution

where is the probability density

where is the Kronecker delta function on

. Using the spectral definition of expansion, we thus see that

is a one-sided expander if and only if

whenever is orthogonal to the constant function

, and is a two-sided expander if

whenever is orthogonal to the constant function

.

We remark that the above spectral definition of expansion can be easily extended to symmetric sets which contain the identity or have multiplicity (i.e. are multisets). (We retain symmetry, though, in order to keep the operation of convolution by

self-adjoint.) In particular, one can say (with some slight abuse of notation) that a set of elements

of

(possibly with repetition, and possibly with some elements equalling the identity) generates a one-sided or two-sided

-expander if the associated symmetric probability density

obeys either (2) or (3).

We saw in the last set of notes that expansion can be characterised in terms of random walks. One can of course specialise this characterisation to the Cayley graph case:

Exercise 11 (Random walk description of expansion) Let

be a family of finite

-regular Cayley graphs, and let

be the associated probability density functions. Let

be a constant.

- Show that the

are a two-sided expander family if and only if there exists a

such that for all sufficiently large

, one has

for some

, where

denotes the convolution of

copies of

.

- Show that the

are a one-sided expander family if and only if there exists a

such that for all sufficiently large

, one has

for some

.

In this set of notes, we will connect expansion of Cayley graphs to an important property of certain infinite groups, known as Kazhdan’s property (T) (or property (T) for short). In 1973, Margulis exploited this property to create the first known explicit and deterministic examples of expanding Cayley graphs. As it turns out, property (T) is somewhat overpowered for this purpose; in particular, we now know that there are many families of Cayley graphs for which the associated infinite group does not obey property (T) (or weaker variants of this property, such as property ). In later notes we will therefore turn to other methods of creating Cayley graphs that do not rely on property (T). Nevertheless, property (T) is of substantial intrinsic interest, and also has many connections to other parts of mathematics than the theory of expander graphs, so it is worth spending some time to discuss it here.

The material here is based in part on this recent text on property (T) by Bekka, de la Harpe, and Valette (available online here).

Read the rest of this entry »

In most undergraduate courses, groups are first introduced as a primarily algebraic concept – a set equipped with a number of algebraic operations (group multiplication, multiplicative inverse, and multiplicative identity) and obeying a number of rules of algebra (most notably the associative law). It is only somewhat later that one learns that groups are not solely an algebraic object, but can also be equipped with the structure of a manifold (giving rise to Lie groups) or a topological space (giving rise to topological groups). (See also this post for a number of other ways to think about groups.)

Another important way to enrich the structure of a group is to give it some geometry. A fundamental way to provide such a geometric structure is to specify a list of generators

of the group

. Let us call such a pair

a generated group; in many important cases the set of generators

is finite, leading to a finitely generated group. A generated group

gives rise to the word metric

on

, defined to be the maximal metric for which

for all

and

(or more explicitly,

is the least

for which

for some

and

). This metric then generates the balls

. In the finitely generated case, the

are finite sets, and the rate at which the cardinality of these sets grow in

is an important topic in the field of geometric group theory. The idea of studying a finitely generated group via the geometry of its metric goes back at least to the work of Dehn.

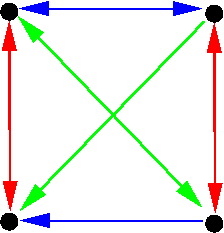

One way to visualise the geometry of a generated group is to look at the (labeled) Cayley colour graph of the generated group . This is a directed coloured graph, with edges coloured by the elements of

, and vertices labeled by elements of

, with a directed edge of colour

from

to

for each

and

. The word metric then corresponds to the graph metric of the Cayley graph.

For instance, the Cayley graph of the cyclic group with a single generator

(which we draw in green) is given as

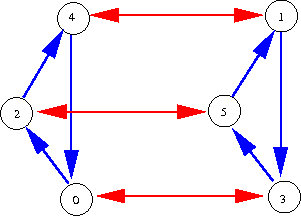

while the Cayley graph of the same group but with the generators (which we draw in blue and red respectively) is given as

We can thus see that the same group can have somewhat different geometry if one changes the set of generators. For instance, in a large cyclic group , with a single generator

the Cayley graph “looks one-dimensional”, and balls

grow linearly in

until they saturate the entire group, whereas with two generators

chosen at random, the Cayley graph “looks two-dimensional”, and the balls

typically grow quadratically until they saturate the entire group.

Cayley graphs have three distinguishing properties:

- (Regularity) For each colour

, every vertex

has a single

-edge leading out of

, and a single

-edge leading into

.

- (Connectedness) The graph is connected.

- (Homogeneity) For every pair of vertices

, there is a unique coloured graph isomorphism that maps

to

.

It is easy to verify that a directed coloured graph is a Cayley graph (up to relabeling) if and only if it obeys the above three properties. Indeed, given a graph with the above properties, one sets

to equal the (coloured) automorphism group of the graph

; arbitrarily designating one of the vertices of

to be the identity element

, we can then identify all the other vertices in

with a group element. One then identifies each colour

with the vertex that one reaches from

by an

-coloured edge. Conversely, every Cayley graph of a generated group

is clearly regular, is connected because

generates

, and has isomorphisms given by right multiplication

for all

. (The regularity and connectedness properties already ensure the uniqueness component of the homogeneity property.)

From the above equivalence, we see that we do not really need the vertex labels on the Cayley graph in order to describe a generated group, and so we will now drop these labels and work solely with unlabeled Cayley graphs, in which the vertex set is not already identified with the group. As we saw above, one just needs to designate a marked vertex of the graph as the “identity” or “origin” in order to turn an unlabeled Cayley graph into a labeled Cayley graph; but from homogeneity we see that all vertices of an unlabeled Cayley graph “look the same” and there is no canonical preference for choosing one vertex as the identity over another. I prefer here to keep the graphs unlabeled to emphasise the homogeneous nature of the graph.

It is instructive to revisit the basic concepts of group theory using the language of (unlabeled) Cayley graphs, and to see how geometric many of these concepts are. In order to facilitate the drawing of pictures, I work here only with small finite groups (or Cayley graphs), but the discussion certainly is applicable to large or infinite groups (or Cayley graphs) also.

For instance, in this setting, the concept of abelianness is analogous to that of a flat (zero-curvature) geometry: given any two colours , a directed path with colours

(adopting the obvious convention that the reversal of an

-coloured directed edge is considered an

-coloured directed edge) returns to where it started. (Note that a generated group

is abelian if and only if the generators in

pairwise commute with each other.) Thus, for instance, the two depictions of

above are abelian, whereas the group

, which is also the dihedral group of the triangle and thus admits the Cayley graph

is not abelian.

A subgroup of a generated group

can be easily described in Cayley graph language if the generators

of

happen to be a subset of the generators

of

. In that case, if one begins with the Cayley graph of

and erases all colours except for those colours in

, then the graph foliates into connected components, each of which is isomorphic to the Cayley graph of

. For instance, in the above Cayley graph depiction of

, erasing the blue colour leads to three copies of the red Cayley graph (which has

as its structure group), while erasing the red colour leads to two copies of the blue Cayley graph (which as

as its structure group). If

is not contained in

, then one has to first “change basis” and add or remove some coloured edges to the original Cayley graph before one can obtain this formulation (thus for instance

contains two more subgroups of order two that are not immediately apparent with this choice of generators). Nevertheless the geometric intuition that subgroups are analogous to foliations is still quite a good one.

We saw that a subgroup of a generated group

with

foliates the larger Cayley graph into

-connected components, each of which is a copy of the smaller Cayley graph. The remaining colours in

then join those

-components to each other. In some cases, each colour

will connect a

-component to exactly one other

-component; this is the case for instance when one splits

into two blue components. In other cases, a colour

can connect a

-component to multiple

-components; this is the case for instance when one splits

into three red components. The former case occurs precisely when the subgroup

is normal. (Note that a subgroup

of a generated group

is normal if and only if left-multiplication by a generator of

maps right-cosets of

to right-cosets of

.) We can then quotient out the

Cayley graph from

, leading to a quotient Cayley graph

whose vertices are the

-connected components of

, and the edges are projected from

in the obvious manner. We can then view the original graph

as a bundle of

-graphs over a base

-graph (or equivalently, an extension of the base graph

by the fibre graph

); for instance

can be viewed as a bundle of the blue graph

over the red graph

, but not conversely. We thus see that the geometric analogue of the concept of a normal subgroup is that of a bundle. The generators in

can be viewed as describing a connection on that bundle.

Note, though, that the structure group of this connection is not simply , unless

is a central subgroup; instead, it is the larger group

, the semi-direct product of

with its automorphism group. This is because a non-central subgroup

can be “twisted around” by operations such as conjugation

by a generator

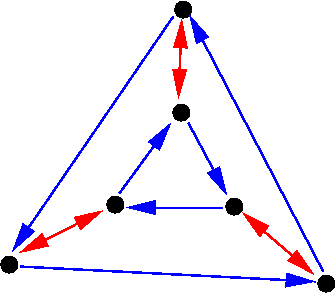

. So central subgroups are analogous to the geometric notion of a principal bundle. For instance, here is the Heisenberg group

over the field of two elements, which one can view as a central extension of

(the blue and green edges, after quotienting) by

(the red edges):

Note how close this group is to being abelian; more generally, one can think of nilpotent groups as being a slight perturbation of abelian groups.

In the case of (viewed as a bundle of the blue graph

over the red graph

), the base graph

is in fact embedded (three times) into the large graph

. More generally, the base graph

can be lifted back into the extension

if and only if the short exact sequence

splits, in which case

becomes a semidirect product

of

and a lifted copy

of

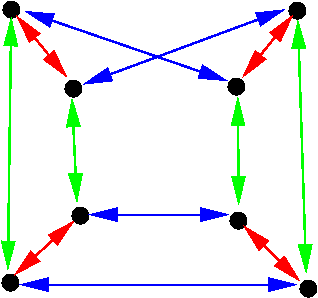

. Not all bundles can be split in this fashion. For instance, consider the group

, with the blue generator

and the red generator

:

This is a -bundle over

that does not split; the blue Cayley graph of

is not visible in the

graph directly, but only after one quotients out the red fibre subgraph. The notion of a splitting in group theory is analogous to the geometric notion of a global gauge. The existence of such a splitting or gauge, and the relationship between two such splittings or gauges, are controlled by the group cohomology of the sequence

.

Even when one has a splitting, the bundle need not be completely trivial, because the bundle is not principal, and the connection can still twist the fibres around. For instance, when viewed as a bundle over

with fibres

splits, but observe that if one uses the red generator of this splitting to move from one copy of the blue

graph to the other, that the orientation of the graph changes. The bundle is trivialisable if and only if

is a direct summand of

, i.e.

splits as a direct product

of a lifted copy

of

. Thus we see that the geometric analogue of a direct summand is that of a trivialisable bundle (and that trivial bundles are then the analogue of direct products). Note that there can be more than one way to trivialise a bundle. For instance, with the Klein four-group

,

the red fibre is a direct summand, but one can use either the blue lift of

or the green lift of

as the complementary factor.

Emmanuel Breuillard, Ben Green, and I have just uploaded to the arXiv our paper “Approximate subgroups of linear groups“, submitted to GAFA. This paper contains (the first part) of the results announced previously by us; the second part of these results, concerning expander groups, will appear subsequently. The release of this paper has been coordinated with the release of a parallel paper by Pyber and Szabo (previously announced within an hour(!) of our own announcement).

Our main result describes (with polynomial accuracy) the “sufficiently Zariski dense” approximate subgroups of simple algebraic groups , or more precisely absolutely almost simple algebraic groups over

, such as

. More precisely, define a

-approximate subgroup of a genuine group

to be a finite symmetric neighbourhood of the identity

(thus

and

) such that the product set

can be covered by

left-translates (and equivalently,

right-translates) of

.

Let be a field, and let

be its algebraic closure. For us, an absolutely almost simple algebraic group over

is a linear algebraic group

defined over

(i.e. an algebraic subvariety of

for some

with group operations given by regular maps) which is connected (i.e. irreducible), and such that the completion

has no proper normal subgroups of positive dimension (i.e. the only normal subgroups are either finite, or are all of

. To avoid degeneracies we also require

to be non-abelian (i.e. not one-dimensional). These groups can be classified in terms of their associated finite-dimensional simple complex Lie algebra, which of course is determined by its Dynkin diagram, together with a choice of weight lattice (and there are only finitely many such choices once the Lie algebra is fixed). However, the exact classification of these groups is not directly used in our work.

Our first main theorem classifies the approximate subgroups of such a group

in the model case when

generates the entire group

, and

is finite; they are either very small or very large.

Theorem 1 (Approximate groups that generate) Let

be an absolutely almost simple algebraic group over

. If

is finite and

is a

-approximate subgroup of

that generates

, then either

or

, where the implied constants depend only on

.

The hypothesis that generates

cannot be removed completely, since if

was a proper subgroup of

of size intermediate between that of the trivial group and of

, then the conclusion would fail (with

). However, one can relax the hypothesis of generation to that of being sufficiently Zariski-dense in

. More precisely, we have

Theorem 2 (Zariski-dense approximate groups) Let

be an absolutely almost simple algebraic group over

. If

is a

-approximate group) is not contained in any proper algebraic subgroup of

of complexity at most

(where

is sufficiently large depending on

), then either

or

, where the implied constants depend only on

and

is the group generated by

.

Here, we say that an algebraic variety has complexity at most if it can be cut out of an ambient affine or projective space of dimension at most

by using at most

polynomials, each of degree at most

. (Note that this is not an intrinsic notion of complexity, but will depend on how one embeds the algebraic variety into an ambient space; but we are assuming that our algebraic group

is a linear group and thus comes with such an embedding.)

In the case when , the second option of this theorem cannot occur since

is infinite, leading to a satisfactory classification of the Zariski-dense approximate subgroups of almost simple connected algebraic groups over

. On the other hand, every approximate subgroup of

is Zariski-dense in some algebraic subgroup, which can be then split as an extension of a semisimple algebraic quotient group by a solvable algebraic group (the radical of the Zariski closure). Pursuing this idea (and glossing over some annoying technical issues relating to connectedness), together with the Freiman theory for solvable groups over

due to Breuillard and Green, we obtain our third theorem:

Theorem 3 (Freiman’s theorem in

) Let

be a

-approximate subgroup of

. Then there exists a nilpotent

-approximate subgroup

of size at most

, such that

is covered by

translates of

.

This can be compared with Gromov’s celebrated theorem that any finitely generated group of polynomial growth is virtually nilpotent. Indeed, the above theorem easily implies Gromov’s theorem in the case of finitely generated subgroups of .

By fairly standard arguments, the above classification theorems for approximate groups can be used to give bounds on the expansion and diameter of Cayley graphs, for instance one can establish a conjecture of Babai and Seress that connected Cayley graphs on absolutely almost simple groups over a finite field have polylogarithmic diameter at most. Applications to expanders include the result on Suzuki groups mentioned in a previous post; further applications will appear in a forthcoming paper.

Apart from the general structural theory of algebraic groups, and some quantitative analogues of the basic theory of algebraic geometry (which we chose to obtain via ultrafilters, as discussed in this post), we rely on two basic tools. Firstly, we use a version of the pivot argument developed first by Konyagin and Bourgain-Glibichuk-Konyagin in the setting of sum-product estimates, and generalised to more non-commutative settings by Helfgott; this is discussed in this previous post. Secondly, we adapt an argument of Larsen and Pink (which we learned from a paper of Hrushovski) to obtain a sharp bound on the extent to which a sufficiently Zariski-dense approximate groups can concentrate in a (bounded complexity) subvariety; this is discussed at the end of this blog post.

This week there is a conference here at IPAM on expanders in pure and applied mathematics. I was an invited speaker, but I don’t actually work in expanders per se (though I am certainly interested in them). So I spoke instead about the recent simplified proof by Kleiner of the celebrated theorem of Gromov on groups of polynomial growth. (This proof does not directly mention expanders, but the argument nevertheless hinges on the absence of expansion in the Cayley graph of a group of polynomial growth, which is exhibited through the smoothness properties of harmonic functions on such graphs.)

Recent Comments