You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘math.MG’ category.

Jan Grebik, Rachel Greenfeld, Vaclav Rozhon and I have just uploaded to the arXiv our preprint “Measurable tilings by abelian group actions“. This paper is related to an earlier paper of Rachel Greenfeld and myself concerning tilings of lattices , but now we consider the more general situation of tiling a measure space

by a tile

shifted by a finite subset

of shifts of an abelian group

that acts in a measure-preserving (or at least quasi-measure-preserving) fashion on

. For instance,

could be a torus

,

could be a positive measure subset of that torus, and

could be the group

, acting on

by translation.

If is a finite subset of

with the property that the translates

,

of

partition

up to null sets, we write

, and refer to this as a measurable tiling of

by

(with tiling set

). For instance, if

is the torus

, we can create a measurable tiling with

and

. Our main results are the following:

- By modifying arguments from previous papers (including the one with Greenfeld mentioned above), we can establish the following “dilation lemma”: a measurable tiling

automatically implies further measurable tilings

, whenever

is an integer coprime to all primes up to the cardinality

of

.

- By averaging the above dilation lemma, we can also establish a “structure theorem” that decomposes the indicator function

of

into components, each of which are invariant with respect to a certain shift in

. We can establish this theorem in the case of measure-preserving actions on probability spaces via the ergodic theorem, but one can also generalize to other settings by using the device of “measurable medial means” (which relates to the concept of a universally measurable set).

- By applying this structure theorem, we can show that all measurable tilings

of the one-dimensional torus

are rational, in the sense that

lies in a coset of the rationals

. This answers a recent conjecture of Conley, Grebik, and Pikhurko; we also give an alternate proof of this conjecture using some previous results of Lagarias and Wang.

- For tilings

of higher-dimensional tori, the tiling need not be rational. However, we can show that we can “slide” the tiling to be rational by giving each translate

of

a “velocity”

, and for every time

, the translates

still form a partition of

modulo null sets, and at time

the tiling becomes rational. In particular, if a set

can tile a torus in an irrational fashion, then it must also be able to tile the torus in a rational fashion.

- In the two-dimensional case

one can arrange matters so that all the velocities

are parallel. If we furthermore assume that the tile

is connected, we can also show that the union of all the translates

with a common velocity

form a

-invariant subset of the torus.

- Finally, we show that tilings

of a finitely generated discrete group

, with

a finite group, cannot be constructed in a “local” fashion (we formalize this probabilistically using the notion of a “factor of iid process”) unless the tile

is contained in a single coset of

. (Nonabelian local tilings, for instance of the sphere by rotations, are of interest due to connections with the Banach-Tarski paradox; see the aforementioned paper of Conley, Grebik, and Pikhurko. Unfortunately, our methods seem to break down completely in the nonabelian case.)

I’ve just uploaded to the arXiv my preprint “Perfectly packing a square by squares of nearly harmonic sidelength“. This paper concerns a variant of an old problem of Meir and Moser, who asks whether it is possible to perfectly pack squares of sidelength for

into a single square or rectangle of area

. (The following variant problem, also posed by Meir and Moser and discussed for instance in this MathOverflow post, is perhaps even more well known: is it possible to perfectly pack rectangles of dimensions

for

into a single square of area

?) For the purposes of this paper, rectangles and squares are understood to have sides parallel to the axes, and a packing is perfect if it partitions the region being packed up to sets of measure zero. As one partial result towards these problems, it was shown by Paulhus that squares of sidelength

for

can be packed (not quite perfectly) into a single rectangle of area

, and rectangles of dimensions

for

can be packed (again not quite perfectly) into a single square of area

. (Paulhus’s paper had some gaps in it, but these were subsequently repaired by Grzegorek and Januszewski.)

Another direction in which partial progress has been made is to consider instead the problem of packing squares of sidelength ,

perfectly into a square or rectangle of total area

, for some fixed constant

(this lower bound is needed to make the total area

finite), with the aim being to get

as close to

as possible. Prior to this paper, the most recent advance in this direction was by Januszewski and Zielonka last year, who achieved such a packing in the range

.

In this paper we are able to get arbitrarily close to

(which turns out to be a “critical” value of this parameter), but at the expense of deleting the first few tiles:

Theorem 1 If, and

is sufficiently large depending on

, then one can pack squares of sidelength

,

perfectly into a square of area

.

As in previous works, the general strategy is to execute a greedy algorithm, which can be described somewhat incompletely as follows.

- Step 1: Suppose that one has already managed to perfectly pack a square

of area

by squares of sidelength

for

, together with a further finite collection

of rectangles with disjoint interiors. (Initially, we would have

and

, but these parameter will change over the course of the algorithm.)

- Step 2: Amongst all the rectangles in

, locate the rectangle

of the largest width (defined as the shorter of the two sidelengths of

).

- Step 3: Pack (as efficiently as one can) squares of sidelength

for

into

for some

, and decompose the portion of

not covered by this packing into rectangles

.

- Step 4: Replace

by

, replace

by

, and return to Step 1.

The main innovation of this paper is to perform Step 3 somewhat more efficiently than in previous papers.

The above algorithm can get stuck if one reaches a point where one has already packed squares of sidelength for

, but that all remaining rectangles

in

have width less than

, in which case there is no obvious way to fit in the next square. If we let

and

denote the width and height of these rectangles

, then the total area of the rectangles must be

In comparison, the perimeter of the squares that one has already packed is equal to

By choosing the parameter suitably large (and taking

sufficiently large depending on

), one can then prove the theorem. (In order to do some technical bookkeeping and to allow one to close an induction in the verification of the algorithm’s correctness, it is convenient to replace the perimeter

by a slightly weighted variant

for a small exponent

, but this is a somewhat artificial device that somewhat obscures the main ideas.)

Given three points in the plane, the distances

between them have to be non-negative and obey the triangle inequalities

but are otherwise unconstrained. But if one has four points in the plane, then there is an additional constraint connecting the six distances

between them, coming from the Cayley-Menger determinant:

Proposition 1 (Cayley-Menger determinant) If

are four points in the plane, then the Cayley-Menger determinant

vanishes.

Proof: If we view as vectors in

, then we have the usual cosine rule

, and similarly for all the other distances. The

matrix appearing in (1) can then be written as

, where

is the matrix

and is the (augmented) Gram matrix

The matrix is a rank one matrix, and so

is also. The Gram matrix

factorises as

, where

is the

matrix with rows

, and thus has rank at most

. Therefore the matrix

in (1) has rank at most

, and hence has determinant zero as claimed.

For instance, if we know that and

, then in order for

to be coplanar, the remaining distance

has to obey the equation

After some calculation the left-hand side simplifies to , so the non-negative quantity is constrained to equal either

or

. The former happens when

form a unit right-angled triangle with right angle at

and

; the latter happens when

form the vertices of a unit square traversed in that order. Any other value for

is not compatible with the hypothesis for

lying on a plane; hence the Cayley-Menger determinant can be used as a test for planarity.

Now suppose that we have four points on a sphere

of radius

, with six distances

now measured as lengths of arcs on the sphere. There is a spherical analogue of the Cayley-Menger determinant:

Proposition 2 (Spherical Cayley-Menger determinant) If

are four points on a sphere

of radius

in

, then the spherical Cayley-Menger determinant

vanishes.

Proof: We can assume that the sphere is centred at the origin of

, and view

as vectors in

of magnitude

. The angle subtended by

from the origin is

, so by the cosine rule we have

Similarly for all the other inner products. Thus the matrix in (2) can be written as , where

is the Gram matrix

We can factor where

is the

matrix with rows

. Thus

has rank at most

and thus the determinant vanishes as required.

Just as the Cayley-Menger determinant can be used to test for coplanarity, the spherical Cayley-Menger determinant can be used to test for lying on a sphere of radius . For instance, if we know that

lie on

and

are all equal to

, then the above proposition gives

The left-hand side evaluates to ; as

lies between

and

, the only choices for this distance are then

and

. The former happens for instance when

lies on the north pole

,

are points on the equator with longitudes differing by 90 degrees, and

is also equal to the north pole; the latter occurs when

is instead placed on the south pole.

The Cayley-Menger and spherical Cayley-Menger determinants look slightly different from each other, but one can transform the latter into something resembling the former by row and column operations. Indeed, the determinant (2) can be rewritten as

and by further row and column operations, this determinant vanishes if and only if the determinant

vanishes, where . In the limit

(so that the curvature of the sphere

tends to zero),

tends to

, and by Taylor expansion

tends to

; similarly for the other distances. Now we see that the planar Cayley-Menger determinant emerges as the limit of (3) as

, as would be expected from the intuition that a plane is essentially a sphere of infinite radius.

In principle, one can now estimate the radius of the Earth (assuming that it is either a sphere

or a flat plane

) if one is given the six distances

between four points

on the Earth. Of course, if one wishes to do so, one should have

rather far apart from each other, since otherwise it would be difficult to for instance distinguish the round Earth from a flat one. As an experiment, and just for fun, I wanted to see how accurate this would be with some real world data. I decided to take

,

,

,

be the cities of London, Los Angeles, Tokyo, and Dubai respectively. As an initial test, I used distances from this online flight calculator, measured in kilometers:

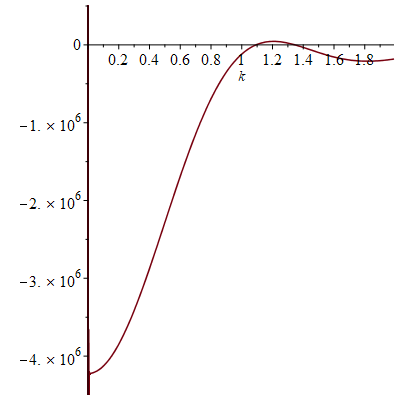

Given that the true radius of the earth was about kilometers, I chose the change of variables

(so that

corresponds to the round Earth model with the commonly accepted value for the Earth’s radius, and

corresponds to the flat Earth), and obtained the following plot for (3):

In particular, the determinant does indeed come very close to vanishing when , which is unsurprising since, as explained on the web site, the online flight calculator uses a model in which the Earth is an ellipsoid of radii close to

km. There is another radius that would also be compatible with this data at

(corresponding to an Earth of radius about

km), but presumably one could rule out this as a spurious coincidence by experimenting with other quadruples of cities than the ones I selected. On the other hand, these distances are highly incompatible with the flat Earth model

; one could also see this with a piece of paper and a ruler by trying to lay down four points

on the paper with (an appropriately rescaled) version of the above distances (e.g., with

,

, etc.).

If instead one goes to the flight time calculator and uses flight travel times instead of distances, one now gets the following data (measured in hours):

Assuming that planes travel at about kilometers per hour, the true radius of the Earth should be about

of flight time. If one then uses the normalisation

, one obtains the following plot:

Not too surprisingly, this is basically a rescaled version of the previous plot, with vanishing near and at

. (The website for the flight calculator does say it calculates short and long haul flight times slightly differently, which may be the cause of the slight discrepancies between this figure and the previous one.)

Of course, these two data sets are “cheating” since they come from a model which already presupposes what the radius of the Earth is. But one can input real world flight times between these four cities instead of the above idealised data. Here one runs into the issue that the flight time from to

is not necessarily the same as that from

to

due to such factors as windspeed. For instance, I looked up the online flight time from Tokyo to Dubai to be 11 hours and 10 minutes, whereas the online flight time from Dubai to Tokyo was 9 hours and 50 minutes. The simplest thing to do here is take an arithmetic mean of the two times as a preliminary estimate for the flight time without windspeed factors, thus for instance the Tokyo-Dubai flight time would now be 10 hours and 30 minutes, and more generally

This data is not too far off from the online calculator data, but it does distort the graph slightly (taking as before):

Now one gets estimates for the radius of the Earth that are off by about a factor of from the truth, although the

round Earth model still is twice as accurate as the flat Earth model

.

Given that windspeed should additively affect flight velocity rather than flight time, and the two are inversely proportional to each other, it is more natural to take a harmonic mean rather than an arithmetic mean. This gives the slightly different values

but one still gets essentially the same plot:

So the inaccuracies are presumably coming from some other source. (Note for instance that the true flight time from Tokyo to Dubai is about greater than the calculator predicts, while the flight time from LA to Dubai is about

less; these sorts of errors seem to pile up in this calculation.) Nevertheless, it does seem that flight time data is (barely) enough to establish the roundness of the Earth and obtain a somewhat ballpark estimate for its radius. (I assume that the fit would be better if one could include some Southern Hemisphere cities such as Sydney or Santiago, but I was not able to find a good quadruple of widely spaced cities on both hemispheres for which there were direct flights between all six pairs.)

Previous set of notes: Notes 1. Next set of notes: Notes 3.

We now leave the topic of Riemann surfaces, and turn now to the (loosely related) topic of conformal mapping (and quasiconformal mapping). Recall that a conformal map from an open subset

of the complex plane to another open set

is a map that is holomorphic and bijective, which (by Rouché’s theorem) also forces the derivative of

to be nowhere vanishing. We then say that the two open sets

are conformally equivalent. From the Cauchy-Riemann equations we see that conformal maps are orientation-preserving and angle-preserving; from the Newton approximation

we see that they almost preserve small circles, indeed for

small the circle

will approximately map to

.

In previous quarters, we proved a fundamental theorem about this concept, the Riemann mapping theorem:

Theorem 1 (Riemann mapping theorem) Let

be a simply connected open subset of

that is not all of

. Then

is conformally equivalent to the unit disk

.

This theorem was proven in these 246A lecture notes, using an argument of Koebe. At a very high level, one can sketch Koebe’s proof of the Riemann mapping theorem as follows: among all the injective holomorphic maps from

to

that map some fixed point

to

, pick one that maximises the magnitude

of the derivative (ignoring for this discussion the issue of proving that a maximiser exists). If

avoids some point in

, one can compose

with various holomorphic maps and use Schwarz’s lemma and the chain rule to increase

without destroying injectivity; see the previous lecture notes for details. The conformal map

is unique up to Möbius automorphisms of the disk; one can fix the map by picking two distinct points

in

, and requiring

to be zero and

to be positive real.

It is a beautiful observation of Thurston that the concept of a conformal mapping has a discrete counterpart, namely the mapping of one circle packing to another. Furthermore, one can run a version of Koebe’s argument (using now a discrete version of Perron’s method) to prove the Riemann mapping theorem through circle packings. In principle, this leads to a mostly elementary approach to conformal geometry, based on extremely classical mathematics that goes all the way back to Apollonius. However, in order to prove the basic existence and uniqueness theorems of circle packing, as well as the convergence to conformal maps in the continuous limit, it seems to be necessary (or at least highly convenient) to use much more modern machinery, including the theory of quasiconformal mapping, and also the Riemann mapping theorem itself (so in particular we are not structuring these notes to provide a completely independent proof of that theorem, though this may well be possible).

To make the above discussion more precise we need some notation.

Definition 2 (Circle packing) A (finite) circle packing is a finite collection

of circles

in the complex numbers indexed by some finite set

, whose interiors are all disjoint (but which are allowed to be tangent to each other), and whose union is connected. The nerve of a circle packing is the finite graph whose vertices

are the centres of the circle packing, with two such centres connected by an edge if the circles are tangent. (In these notes all graphs are undirected, finite and simple, unless otherwise specified.)

It is clear that the nerve of a circle packing is connected and planar, since one can draw the nerve by placing each vertex (tautologically) in its location in the complex plane, and drawing each edge by the line segment between the centres of the circles it connects (this line segment will pass through the point of tangency of the two circles). Later in these notes we will also have to consider some infinite circle packings, most notably the infinite regular hexagonal circle packing.

The first basic theorem in the subject is the following converse statement:

Theorem 3 (Circle packing theorem) Every connected planar graph is the nerve of a circle packing.

Among other things, the circle packing theorem thus implies as a corollary Fáry’s theorem that every planar graph can be drawn using straight lines.

Of course, there can be multiple circle packings associated to a given connected planar graph; indeed, since reflections across a line and Möbius transformations map circles to circles (or lines), they will map circle packings to circle packings (unless one or more of the circles is sent to a line). It turns out that once one adds enough edges to the planar graph, the circle packing is otherwise rigid:

Theorem 4 (Koebe-Andreev-Thurston theorem) If a connected planar graph is maximal (i.e., no further edge can be added to it without destroying planarity), then the circle packing given by the above theorem is unique up to reflections and Möbius transformations.

Exercise 5 Let

be a connected planar graph with

vertices. Show that the following are equivalent:

- (i)

is a maximal planar graph.

- (ii)

has

edges.

- (iii) Every drawing

of

divides the plane into faces that have three edges each, and each edge is adjacent to two distinct faces. (This includes one unbounded face.)

- (iv) At least one drawing

of

divides the plane into faces that have three edges each, and each edge is adjacent to two distinct faces.

(Hint: you may use without proof Euler’s formula

for planar graphs, where

is the number of faces including the unbounded face.)

Thurston conjectured that circle packings can be used to approximate the conformal map arising in the Riemann mapping theorem. Here is an informal statement:

Conjecture 6 (Informal Thurston conjecture) Let

be a simply connected domain, with two distinct points

. Let

be the conformal map from

to

that maps

to the origin and

to a positive real. For any small

, let

be the portion of the regular hexagonal circle packing by circles of radius

that are contained in

, and let

be an circle packing of

with the same nerve (up to isomorphism) as

, with all “boundary circles” tangent to

, giving rise to an “approximate map”

defined on the subset

of

consisting of the circles of

, their interiors, and the interstitial regions between triples of mutually tangent circles. Normalise this map so that

is zero and

is a positive real. Then

converges to

as

.

A rigorous version of this conjecture was proven by Rodin and Sullivan. Besides some elementary geometric lemmas (regarding the relative sizes of various configurations of tangent circles), the main ingredients are a rigidity result for the regular hexagonal circle packing, and the theory of quasiconformal maps. Quasiconformal maps are what seem on the surface to be a very broad generalisation of the notion of a conformal map. Informally, conformal maps take infinitesimal circles to infinitesimal circles, whereas quasiconformal maps take infinitesimal circles to infinitesimal ellipses of bounded eccentricity. In terms of Wirtinger derivatives, conformal maps obey the Cauchy-Riemann equation , while (sufficiently smooth) quasiconformal maps only obey an inequality

. As such, quasiconformal maps are considerably more plentiful than conformal maps, and in particular it is possible to create piecewise smooth quasiconformal maps by gluing together various simple maps such as affine maps or Möbius transformations; such piecewise maps will naturally arise when trying to rigorously build the map

alluded to in the above conjecture. On the other hand, it turns out that quasiconformal maps still have many vestiges of the rigidity properties enjoyed by conformal maps; for instance, there are quasiconformal analogues of fundamental theorems in conformal mapping such as the Schwarz reflection principle, Liouville’s theorem, or Hurwitz’s theorem. Among other things, these quasiconformal rigidity theorems allow one to create conformal maps from the limit of quasiconformal maps in many circumstances, and this will be how the Thurston conjecture will be proven. A key technical tool in establishing these sorts of rigidity theorems will be the theory of an important quasiconformal (quasi-)invariant, the conformal modulus (or, equivalently, the extremal length, which is the reciprocal of the modulus).

The Polymath14 online collaboration has uploaded to the arXiv its paper “Homogeneous length functions on groups“, submitted to Algebra & Number Theory. The paper completely classifies homogeneous length functions on an arbitrary group

, that is to say non-negative functions that obey the symmetry condition

, the non-degeneracy condition

, the triangle inequality

, and the homogeneity condition

. It turns out that these norms can only arise from pulling back the norm of a Banach space by an isometric embedding of the group. Among other things, this shows that

can only support a homogeneous length function if and only if it is abelian and torsion free, thus giving a metric description of this property.

The proof is based on repeated use of the homogeneous length function axioms, combined with elementary identities of commutators, to obtain increasingly good bounds on quantities such as , until one can show that such norms have to vanish. See the previous post for a full proof. The result is robust in that it allows for some loss in the triangle inequality and homogeneity condition, allowing for some new results on “quasinorms” on groups that relate to quasihomomorphisms.

As there are now a large number of comments on the previous post on this project, this post will also serve as the new thread for any final discussion of this project as it winds down.

In the tradition of “Polymath projects“, the problem posed in the previous two blog posts has now been solved, thanks to the cumulative effect of many small contributions by many participants (including, but not limited to, Sean Eberhard, Tobias Fritz, Siddharta Gadgil, Tobias Hartnick, Chris Jerdonek, Apoorva Khare, Antonio Machiavelo, Pace Nielsen, Andy Putman, Will Sawin, Alexander Shamov, Lior Silberman, and David Speyer). In this post I’ll write down a streamlined resolution, eliding a number of important but ultimately removable partial steps and insights made by the above contributors en route to the solution.

Theorem 1 Let

be a group. Suppose one has a “seminorm” function

which obeys the triangle inequality

for all

, with equality whenever

. Then the seminorm factors through the abelianisation map

.

Proof: By the triangle inequality, it suffices to show that for all

, where

is the commutator.

We first establish some basic facts. Firstly, by hypothesis we have , and hence

whenever

is a power of two. On the other hand, by the triangle inequality we have

for all positive

, and hence by the triangle inequality again we also have the matching lower bound, thus

for all . The claim is also true for

(apply the preceding bound with

and

). By replacing

with

if necessary we may now also assume without loss of generality that

, thus

Next, for any , and any natural number

, we have

so on taking limits as we have

. Replacing

by

gives the matching lower bound, thus we have the conjugation invariance

Next, we observe that if are such that

is conjugate to both

and

, then one has the inequality

Indeed, if we write for some

, then for any natural number

one has

where the and

terms each appear

times. From (2) we see that conjugation by

does not affect the norm. Using this and the triangle inequality several times, we conclude that

and the claim (3) follows by sending .

The following special case of (3) will be of particular interest. Let , and for any integers

, define the quantity

Observe that is conjugate to both

and to

, hence by (3) one has

which by (2) leads to the recursive inequality

We can write this in probabilistic notation as

where is a random vector that takes the values

and

with probability

each. Iterating this, we conclude in particular that for any large natural number

, one has

where and

are iid copies of

. We can write

where

are iid signs. By the triangle inequality, we thus have

noting that is an even integer. On the other hand,

has mean zero and variance

, hence by Cauchy-Schwarz

But by (1), the left-hand side is equal to . Dividing by

and then sending

, we obtain the claim.

The above theorem reduces such seminorms to abelian groups. It is easy to see from (1) that any torsion element of such groups has zero seminorm, so we can in fact restrict to torsion-free groups, which we now write using additive notation , thus for instance

for

. We think of

as a

-module. One can then extend the seminorm to the associated

-vector space

by the formula

, and then to the associated

-vector space

by continuity, at which point it becomes a genuine seminorm (provided we have ensured the symmetry condition

). Conversely, any seminorm on

induces a seminorm on

. (These arguments also appear in this paper of Khare and Rajaratnam.)

This post is a continuation of the previous post, which has attracted a large number of comments. I’m recording here some calculations that arose from those comments (particularly those of Pace Nielsen, Lior Silberman, Tobias Fritz, and Apoorva Khare). Please feel free to either continue these calculations or to discuss other approaches to the problem, such as those mentioned in the remaining comments to the previous post.

Let be the free group on two generators

, and let

be a quantity obeying the triangle inequality

and the linear growth property

for all and integers

; this implies the conjugation invariance

or equivalently

We consider inequalities of the form

for various real numbers . For instance, since

we have (1) for . We also have the following further relations:

Proposition 1

Proof: For (i) we simply observe that

For (ii), we calculate

giving the claim.

For (iii), we calculate

giving the claim.

For (iv), we calculate

giving the claim.

Here is a typical application of the above estimates. If (1) holds for , then by part (i) it holds for

, then by (ii) (2) holds for

, then by (iv) (1) holds for

. The map

has fixed point

, thus

For instance, if , then

.

Here is a curious question posed to me by Apoorva Khare that I do not know the answer to. Let be the free group on two generators

. Does there exist a metric

on this group which is

- bi-invariant, thus

for all

; and

- linear growth in the sense that

for all

and all natural numbers

?

By defining the “norm” of an element to be

, an equivalent formulation of the problem asks if there exists a non-negative norm function

that obeys the conjugation invariance

for all , the triangle inequality

for all , and the linear growth

for all and

, and such that

for all non-identity

. Indeed, if such a norm exists then one can just take

to give the desired metric.

One can normalise the norm of the generators to be at most , thus

This can then be used to upper bound the norm of other words in . For instance, from (1), (3) one has

A bit less trivially, from (3), (2), (1) one can bound commutators as

In a similar spirit one has

What is not clear to me is if one can keep arguing like this to continually improve the upper bounds on the norm of a given non-trivial group element

to the point where this norm must in fact vanish, which would demonstrate that no metric with the above properties on

would exist (and in fact would impose strong constraints on similar metrics existing on other groups as well). It is also tempting to use some ideas from geometric group theory (e.g. asymptotic cones) to try to understand these metrics further, though I wasn’t able to get very far with this approach. Anyway, this feels like a problem that might be somewhat receptive to a more crowdsourced attack, so I am posing it here in case any readers wish to try to make progress on it.

I’ve just uploaded to the arXiv my paper “On the universality of the incompressible Euler equation on compact manifolds“, submitted to Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems. This is a variant of my recent paper on the universality of potential well dynamics, but instead of trying to embed dynamical systems into a potential well , here we try to embed dynamical systems into the incompressible Euler equations

on a Riemannian manifold . (One is particularly interested in the case of flat manifolds

, particularly

or

, but for the main result of this paper it is essential that one is permitted to consider curved manifolds.) This system, first studied by Ebin and Marsden, is the natural generalisation of the usual incompressible Euler equations to curved space; it can be viewed as the formal geodesic flow equation on the infinite-dimensional manifold of volume-preserving diffeomorphisms on

(see this previous post for a discussion of this in the flat space case).

The Euler equations can be viewed as a nonlinear equation in which the nonlinearity is a quadratic function of the velocity field . It is thus natural to compare the Euler equations with quadratic ODE of the form

where is the unknown solution, and

is a bilinear map, which we may assume without loss of generality to be symmetric. One can ask whether such an ODE may be linearly embedded into the Euler equations on some Riemannian manifold

, which means that there is an injective linear map

from

to smooth vector fields on

, as well as a bilinear map

to smooth scalar fields on

, such that the map

takes solutions to (2) to solutions to (1), or equivalently that

for all .

For simplicity let us restrict to be compact. There is an obvious necessary condition for this embeddability to occur, which comes from energy conservation law for the Euler equations; unpacking everything, this implies that the bilinear form

in (2) has to obey a cancellation condition

for some positive definite inner product on

. The main result of the paper is the converse to this statement: if

is a symmetric bilinear form obeying a cancellation condition (3), then it is possible to embed the equations (2) into the Euler equations (1) on some Riemannian manifold

; the catch is that this manifold will depend on the form

and on the dimension

(in fact in the construction I have,

is given explicitly as

, with a funny metric on it that depends on

).

As a consequence, any finite dimensional portion of the usual “dyadic shell models” used as simplified toy models of the Euler equation, can actually be embedded into a genuine Euler equation, albeit on a high-dimensional and curved manifold. This includes portions of the self-similar “machine” I used in a previous paper to establish finite time blowup for an averaged version of the Navier-Stokes (or Euler) equations. Unfortunately, the result in this paper does not apply to infinite-dimensional ODE, so I cannot yet establish finite time blowup for the Euler equations on a (well-chosen) manifold. It does not seem so far beyond the realm of possibility, though, that this could be done in the relatively near future. In particular, the result here suggests that one could construct something resembling a universal Turing machine within an Euler flow on a manifold, which was one ingredient I would need to engineer such a finite time blowup.

The proof of the main theorem proceeds by an “elimination of variables” strategy that was used in some of my previous papers in this area, though in this particular case the Nash embedding theorem (or variants thereof) are not required. The first step is to lessen the dependence on the metric by partially reformulating the Euler equations (1) in terms of the covelocity

(which is a

-form) instead of the velocity

. Using the freedom to modify the dimension of the underlying manifold

, one can also decouple the metric

from the volume form that is used to obtain the divergence-free condition. At this point the metric can be eliminated, with a certain positive definiteness condition between the velocity and covelocity taking its place. After a substantial amount of trial and error (motivated by some “two-and-a-half-dimensional” reductions of the three-dimensional Euler equations, and also by playing around with a number of variants of the classic “separation of variables” strategy), I eventually found an ansatz for the velocity and covelocity that automatically solved most of the components of the Euler equations (as well as most of the positive definiteness requirements), as long as one could find a number of scalar fields that obeyed a certain nonlinear system of transport equations, and also obeyed a positive definiteness condition. Here I was stuck for a bit because the system I ended up with was overdetermined – more equations than unknowns. After trying a number of special cases I eventually found a solution to the transport system on the sphere, except that the scalar functions sometimes degenerated and so the positive definiteness property I wanted was only obeyed with positive semi-definiteness. I tried for some time to perturb this example into a strictly positive definite solution before eventually working out that this was not possible. Finally I had the brainwave to lift the solution from the sphere to an even more symmetric space, and this quickly led to the final solution of the problem, using the special orthogonal group rather than the sphere as the underlying domain. The solution ended up being rather simple in form, but it is still somewhat miraculous to me that it exists at all; in retrospect, given the overdetermined nature of the problem, relying on a large amount of symmetry to cut down the number of equations was basically the only hope.

Recent Comments