Kari Astala, Steffen Rohde, Eero Saksman and I have (finally!) uploaded to the arXiv our preprint “Homogenization of iterated singular integrals with applications to random quasiconformal maps“. This project started (and was largely completed) over a decade ago, but for various reasons it was not finalised until very recently. The motivation for this project was to study the behaviour of “random” quasiconformal maps. Recall that a (smooth) quasiconformal map is a homeomorphism  that obeys the Beltrami equation

that obeys the Beltrami equation

for some

Beltrami coefficient

; this can be viewed as a deformation of the Cauchy-Riemann equation

. Assuming that

is asymptotic to

at infinity, one can (formally, at least) solve for

in terms of

using the

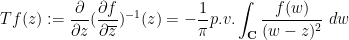

Beurling transform

by the Neumann series

We looked at the question of the asymptotic behaviour of

if

is a random field that oscillates at some fine spatial scale

. A simple model to keep in mind is

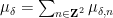

![\displaystyle \mu_\delta(z) = \varphi(z) \sum_{n \in {\bf Z}^2} \epsilon_n 1_{n\delta + [0,\delta]^2}(z) \ \ \ \ \ (1)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle++%5Cmu_%5Cdelta%28z%29+%3D+%5Cvarphi%28z%29+%5Csum_%7Bn+%5Cin+%7B%5Cbf+Z%7D%5E2%7D+%5Cepsilon_n+1_%7Bn%5Cdelta+%2B+%5B0%2C%5Cdelta%5D%5E2%7D%28z%29+%5C+%5C+%5C+%5C+%5C+%281%29&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002)

where

are independent random signs and

is a bump function. For models such as these, we show that a homogenisation occurs in the limit

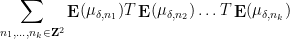

; each multilinear expression

converges weakly in probability (and almost surely, if we restrict

to a lacunary sequence) to a deterministic limit, and the associated quasiconformal map

similarly converges weakly in probability (or almost surely). (Results of this latter type were also recently obtained

by Ivrii and Markovic by a more geometric method which is simpler, but is applied to a narrower class of Beltrami coefficients.) In the specific case

(1), the limiting quasiconformal map is just the identity map

, but if for instance replaces the

by non-symmetric random variables then one can have significantly more complicated limits. The convergence theorem for multilinear expressions such as is not specific to the Beurling transform

; any other translation and dilation invariant singular integral can be used here.

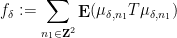

The random expression (2) is somewhat reminiscent of a moment of a random matrix, and one can start computing it analogously. For instance, if one has a decomposition  such as (1), then (2) expands out as a sum

such as (1), then (2) expands out as a sum

The random fluctuations of this sum can be treated by a routine second moment estimate, and the main task is to show that the expected value

becomes asymptotically independent of

.

If all the  were distinct then one could use independence to factor the expectation to get

were distinct then one could use independence to factor the expectation to get

which is a relatively straightforward expression to calculate (particularly in the model

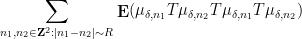

(1), where all the expectations here in fact vanish). The main difficulty is that there are a number of configurations in

(3) in which various of the

collide with each other, preventing one from easily factoring the expression. A typical problematic contribution for instance would be a sum of the form

This is an example of what we call a

non-split sum. This can be compared with the

split sum

If we ignore the constraint

in the latter sum, then it splits into

where

and

and one can hope to treat this sum by an induction hypothesis. (To actually deal with constraints such as

requires an inclusion-exclusion argument that creates some notational headaches but is ultimately manageable.) As the name suggests, the non-split configurations such as

(4) cannot be factored in this fashion, and are the most difficult to handle. A direct computation using the triangle inequality (and a certain amount of combinatorics and induction) reveals that these sums are somewhat localised, in that dyadic portions such as

exhibit power decay in

(when measured in suitable function space norms), basically because of the large number of times one has to transition back and forth between

and

. Thus, morally at least, the dominant contribution to a non-split sum such as

(4) comes from the local portion when

. From the translation and dilation invariance of

this type of expression then simplifies to something like

(plus negligible errors) for some reasonably decaying function

, and this can be shown to converge to a weak limit as

.

In principle all of these limits are computable, but the combinatorics is remarkably complicated, and while there is certainly some algebraic structure to the calculations, it does not seem to be easily describable in terms of an existing framework (e.g., that of free probability).

that obeys the Beltrami equation

such as (1), then (2) expands out as a sum

were distinct then one could use independence to factor the expectation to get

Recent Comments