To progress further in our study of function spaces, we will need to develop the standard theory of metric spaces, and of the closely related theory of topological spaces (i.e. point-set topology). I will be assuming that students in my class will already have encountered these concepts in an undergraduate topology or real analysis course, but for sake of completeness I will briefly review the basics of both spaces here.

— Metric spaces —

In many spaces, one wants a notion of when two points in the space are “near” or “far”. A particularly quantitative and intuitive way to formalise this notion is via the concept of a metric space.

Definition 1. (Metric spaces) A metric space

is a set X, together with a distance function

which obeys the following properties:

- (Non-degeneracy) For any

, we have

, with equality if and only if x=y.

- (Symmetry) For any

, we have

.

- (Triangle inequality) For any

, we have

.

Example 1. Every normed vector space is a metric space, with distance function

.

Example 2. Any subset Y of a metric space is also a metric space

, where

is the restriction of d to

. We call the metric space

a subspace of the metric space

.

Example 3. Given two metric spaces and

, we can define the product space

to be the Cartesian product

with the product metric

. (1)

(One can also pick slightly different metrics here, such as , but this metric only differs from (1) by a factor of two, and so they are equivalent (see Example 5 below).

Example 4. Any set X can be turned into a metric space by using the discrete metric , defined by setting

when

and

otherwise.

Given a metric space, one can then define various useful topological structures. There are two ways to do so. One is via the machinery of convergent sequences:

Definition 2. (Topology of a metric space) Let

be a metric space.

- A sequence

of points in X is said to converge to a limit

if one has

as

. In this case, we say that

in the metric d as

, and that

in the metric space X. (It is easy to see that any sequence of points in a metric space has at most one limit.)

- A point x is an adherent point of a set

if it is the limit of some sequence in E. (This is slightly different from being a limit point of E, which is equivalent to being an adherent point of

; every adherent point is either a limit point or an isolated point of E.) The set of all adherent points of E is called the closure

of X. A set E is closed if it contains all its adherent points, i.e. if

. A set E is dense if every point in X is adherent to E, or equivalently if

.

- Given any x in X and

, define the open ball

centred at x with radius r to be the set of all y in X such that

. Given a set E, we say that x is an interior point of E if there is some open ball centred at x which is contained in E. The set of all interior points is called the interior

of E. A set is open if every point is an interior point, i.e. if

.

There is however an alternate approach to defining these concepts, which takes the concept of an open set as a primitive, rather than the distance function, and defines other terms in terms of open sets. For instance:

Exercise 1. Let be a metric space.

- Show that a sequence

of points in X converges to a limit

if and only if every open neighbourhood of x (i.e. an open set containing x) contains

for all sufficiently large n.

- Show that a point x is an adherent point of a set E if and only if every open neighbourhood of x intersects E.

- Show that a set E is closed if and only if its complement is open.

- Show that the closure of a set E is the intersection of all the closed sets containing E.

- Show that a set E is dense if and only if every non-empty open set intersects E.

- Show that the interior of a set E is the union of all the open sets contained in E, and that x is an interior point of E if and only if some neighbourhood of x is contained in E.

In the next section we will adopt this “open sets first” perspective when defining topological spaces.

On the other hand, there are some other properties of subsets of a metric space which require the metric structure more fully, and cannot be defined purely in terms of open sets (see Example 14) below (although some of these concepts can still be defined using a structure intermediate to metric spaces and topological spaces, namely a uniform space). For instance:

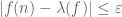

Definition 3. Let (X,d) be a metric space.

- A sequence

of points in X is a Cauchy sequence if

as

(i.e. for every

there exists

such that

for all

).

- A space X is complete if every Cauchy sequence is convergent.

- A set E in X is bounded if it is contained inside a ball.

- A set E is totally bounded in X if for every

, E can be covered by finitely many balls of radius

.

Exercise 2. Show that any metric space can be identified with a dense subspace of a complete metric space

, known as a metric completion or Cauchy completion of X. (For instance,

is a metric completion of

.) (Hint: one can define a real number to be an equivalence class of Cauchy sequences of rationals. Once the reals are defined, essentially the same construction works in arbitrary metric spaces.) Furthermore, if

is another metric completion of

, show that there exists an isometry between

and

which is the identity on X. Thus, up to isometry, there is a unique metric completion to any metric space.

Exercise 3. Show that a metric space X is complete if and only if it is closed in every superspace Y of X (i.e. in every metric space Y for which X is a subspace). Thus one can think of completeness as being the property of being “absolutely closed”.

Exercise 4. Show that every totally bounded set is also bounded. Conversely, in a Euclidean space with the usual metric, show that every bounded set is totally bounded. But give an example of a set in a metric space which is bounded but not totally bounded. (Hint: use Example 4.)

Now we come to an important concept.

Theorem 1. (Heine-Borel theorem for metric spaces) Let

be a metric space. Then the following are equivalent:

- (Sequential compactness) Every sequence in X has a convergent subsequence.

- (Compactness) Every open cover

of X (i.e. a collection of open sets

whose union contains X) has a finite subcover.

- (Finite intersection property) If

is a collection of closed subsets of X such that any finite subcollection of sets has non-empty intersection, then the entire collection has non-empty intersection.

- X is complete and totally bounded.

Proof. (2 1) If there was an infinite sequence

with no convergent subsequence, then given any point x in X there must exist an open ball centred at x which contains

for only finitely many n (since otherwise one could easily construct a subsequence of

converging to x). By property 2, one can cover X with a finite number of such balls. But then the sequence

would be finite, a contradiction.

(1 4) If X was not complete, then there would exist a Cauchy sequence which is not convergent; one easily shows that this sequence cannot have any convergent subsequences either, contradicting 1. If X was not totally bounded, then there exists

such that X cannot be covered by any finite collection of balls of radius

; a standard greedy algorithm argument then gives a sequence

such that

for all distinct n, m. This sequence clearly has no convergent subsequence, again a contradiction.

(2 3) This follows from de Morgan’s laws and Exercise 1.3.

(4 3) Let

be as in 3. Call a set E in X rich if it intersects all of the

. Observe that if one could cover X by a finite number of non-rich sets, then (as each non-rich set is disjoint from at least one of the

), there would be a finite number of

whose intersection is empty, a contradiction. Thus, whenever we cover X by finitely many sets, at least one of them must be rich.

As X is totally bounded, for each we can find a finite set

such that the balls

cover X. By the previous discussion, we can then find

such that

is rich.

Call a ball asymptotically rich if it contains infinitely many of the

. As these balls cover X, we see that for each n,

is asymptotically rich for at least one i. Furthermore, since each ball of radius

can be covered by balls of radius

, we see that if

is asymptotically rich, then it must intersect an asymptotically rich ball

. Iterating this, we can find a sequence

of asymptotically rich balls, each one of which intersects the next one. This implies that

is a Cauchy sequence and hence (as X is assumed complete) converges to a limit x. Observe that there exist arbitrarily small rich balls that are arbitrarily close to x, and thus x is adherent to every

; since the

are closed, we see that x lies in every

, and we are done.

Remark 1. The hard implication of the Heine-Borel theorem is noticeably more complicated than any of the others. This turns out to be unavoidable; the Heine-Borel theorem turns out to be logically equivalent to König’s lemma in the sense of reverse mathematics, and thus cannot be proven in sufficiently weak systems of logical reasoning.

Any space that obeys one of the four equivalent properties in Lemma 1 is called a compact space; a subset E of a metric space X is said to be compact if it is a compact space when viewed as a subspace of X. There are some variants of the notion of compactness which are also of importance for us:

- A space is

-compact if it can be expressed as the countable union of compact sets. (For instance, the real line

with the usual metric is

-compact.)

- A space is locally compact if every point is contained in the interior of a compact set. (For instance,

is locally compact.)

- A subset of a space is precompact or relatively compact if it is contained inside a compact set (or equivalently, if its closure is compact).

Another fundamental notion in the subject is that of a continuous map.

Exercise 5. Let be a map from one metric space

to another

. Then the following are equivalent:

- (Metric continuity) For every

and

there exists

such that

whenever

.

- (Sequential continuity) For every sequence

that converges to a limit

,

converges to f(x).

- (Topological continuity) The inverse image

of every open set V in Y, is an open set in X.

- The inverse image

of every closed set F in Y, is a closed set in X.

A function f obeying any one of the properties in Exercise 5 is known as a continuous map.

Exercise 6. Let be metric spaces, and let

and

be continuous maps. Show that the combined map

defined by

is continuous if and only if f and g are continuous. Show also that the projection maps

,

defined by

,

are continuous.

Exercise 7. Show that the image of a compact set under a continuous map is again compact.

— Topological spaces —

Metric spaces capture many of the notions of convergence and continuity that one commonly uses in real analysis, but there are several such notions (e.g. pointwise convergence, semi-continuity, or weak convergence) in the subject that turn out to not be modeled by metric spaces. A very useful framework to handle these more general modes of convergence and continuity is that of a topological space, which one can think of as an abstract generalisation of a metric space in which the metric and balls are forgotten, and the open sets become the central object. [There are even more abstract notions, such as pointless topological spaces, in which the collection of open sets has become an abstract lattice, in the spirit of Notes 4, but we will not need such notions in this course.]

Definition 4. (Topological space) A topological space

is a set X, together with a collection

of subsets of X, known as open sets, which obey the following axioms:

and X are open.

- The intersection of any finite number of open sets is open.

- The union of any arbitrary number of open sets is open.

The collection

is called a topology on X.

Given two topologies

on a space X, we say that

is a coarser (or weaker) topology than

(or equivalently, that

is a finer (or stronger) topology than

), if

(informally,

has more open sets than

).

Example 5. Every metric space generates a topology

, namely the space of sets which are open with respect to the metric d. Observe that if two metrics d, d’ on X are equivalent in the sense that

(2)

for all x, y in X and some constants , then they generate an identical topology.

Example 6. The finest (or strongest) topology on any set X is the discrete topology , in which every set is open; this is the topology generated by the discrete metric (Example 4). The coarsest (or weakest) topology is the trivial topology

, in which only the empty set and the full set are open.

Example 7. Given any collection of sets of X, we can define the topology

generated by

to be the intersection of all the topologies that contain

; this is easily seen to be the coarsest topology that makes all the sets in

open. For instance, the topology generated by a metric space is the same as the topology generated by its open balls.

Example 8. If is a topological space, and Y is a subset of X, then we can define the relative topology

to be the collection of all open sets in X, restricted to Y, this makes

a topological space, known as a subspace of

.

Any notion in metric space theory which can be defined purely in terms of open sets, can now be defined for topological spaces. Thus for instance:

Definition 5. Let

be a topological space.

- A sequence

of points in X converges to a limit

if and only if every open neighbourhood of x (i.e. an open set containing x) contains

for all sufficiently large n. In this case we write

in the topological space

, and (if x is unique) we write

.

- A point is a sequentially adherent point of a set E if it is the limit of some sequence in E.

- A point x is an adherent point of a set E if and only if every open neighbourhood of x intersects E. The set of all adherent points of E is called the closure of E and is denoted

.

- A set E is closed if and only if its complement is open, or equivalently if it contains all its adherent points.

- A set E is dense if and only if every non-empty open set intersects E, or equivalently if its closure is X.

- The interior of a set E is the union of all the open sets contained in E, and x is called an interior point of E if and only if some neighbourhood of x is contained in E.

- A space X is sequentially compact if every sequence has a convergent subsequence.

- A space X is compact if every open cover has a finite subcover.

- The concepts of being

-compact, locally compact, and precompact can be defined as before. (One could also define sequential

-compactness, etc., but these notions are rarely used.)

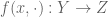

- A map

between topological spaces is sequentially continuous if whenever

converges to a limit x in X,

converges to a limit f(x) in Y.

- A map

between topological spaces is continuous if the inverse image of every open set is open.

Remark 2. The stronger a topology becomes, the more open and closed sets it will have, but fewer sequences will converge, there are fewer (sequentially) adherent points and (sequentially) compact sets, closures become smaller, and interiors become larger. There will be more (sequentially) continuous functions on this space, but fewer (sequentially) continuous functions into the space. Note also that the identity map from a space X with one topology to the same space X with a different topology

is continuous precisely when

is stronger than

.

Example 9. In a metric space, these topological notions coincide with their metric counterparts, and sequential compactness and compactness are equivalent, as are sequential continuity and continuity.

Exercise 7′. (Urysohn’s subsequence principle) Let be a sequence in a topological space X, and let x be another point in X. Show that the following are equivalent:

converges to x.

- Every subsequence of

converges to x.

- Every subsequence of

has a further subsequence that converges to x.

Exercise 8. Show that every sequentially adherent point is an adherent point, every continuous function is sequentially continuous.

Remark 3. The converses to Exercise 8 are unfortunately not always true in general topological spaces. For instance, if we endow an uncountable set X with the cocountable topology (so that a set is open if it is either empty, or its complement is at most countable) then we see that the only convergent sequences are those which are eventually constant. Thus, every subset of X contains its sequentially adherent points, and every function from X to another topological space is sequentially continuous, even though not every set in X is closed and not every function on X is continuous. An example of a set which is sequentially compact but not compact is the first uncountable ordinal with the order topology (Exercise 9). It is more tricky to give an example of a compact space which is not sequentially compact; this will have to wait for future notes, when we establish Tychonoff’s theorem. However one can “fix” this discrepancy between the sequential and non-sequential concepts by replacing sequences with the more general notion of nets, see the appendix below.

Remark 4. Metric space concepts such as boundedness, completeness, Cauchy sequences, and uniform continuity do not have counterparts for general topological spaces, because they cannot be defined purely in terms of open sets. (They can however be extended to some other types of spaces, such as uniform spaces or coarse spaces.)

Now we give some important topologies that capture certain modes of convergence or continuity that are difficult or impossible to capture using metric spaces alone.

Example 10. (Zariski topology) This topology is important in algebraic geometry, though it will not be used in this course. If F is an algebraically closed field, we define the Zariski topology on the vector space to be the topology generated by the complements of proper algebraic varieties in

; thus a set is Zariski open if it is either empty, or is the complement of a finite union of proper algebraic varieties. A set in

is then Zariski dense if it is not contained in any proper subvariety, and the Zariski closure of a set is the smallest algebraic variety that contains that set.

Example 11. (Order topology) Any totally ordered set generates the order topology, defined as the topology generated by the sets

and

for all

. In particular, the extended real line

can be given the order topology, and the notion of convergence of sequences in this topology to either finite or infinite limits is identical to the notion one is accustomed to in undergraduate real analysis. (On the real line, of course, the order topology corresponds to the usual topology.) Also observe that a function

from the extended natural numbers

(with the order topology) into a topological space X is continuous if and only if

as

, so one can interpret convergence of sequences as a special case of continuity.

Exercise 9. Let be the first uncountable ordinal, endowed with the order topology. Show that

is sequentially compact (Hint: every sequence has a lim sup), but not compact (Hint: every point has a countable neighbourhood).

Example 12. (Half-open topology) The right half-open topology on the real line

is the topology generated by the right half-open intervals

for

; this is a bit finer than the usual topology on

. Observe that a sequence

converges to a limit x in the right half-open topology if and only if it converges in the ordinary topology

, and also if

for all sufficiently large n. Observe that a map

is right-continuous iff it is a continuous map from

to

. One can of course model left-continuity via a suitable left half-open topology in a similar fashion.

Example 13. (Upper topology) The upper topology on the real line is defined as the topology generated by the sets

for all

. Observe that (somewhat confusingly), a function

is lower semi-continuous iff it is continuous from

to

. One can of course model upper semi-continuity via a suitable lower topology in a similar fashion.

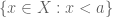

Example 14. (Product topology) Let be the space of all functions

from a set X to a topological space Y. We define the product topology on

to be the topology generated by the sets

for all

and all open

. Observe that a sequence of functions

converges pointwise to a limit

iff it converges in the product topology. We will study the product topology in more depth in future notes.

Example 15. (Product topology, again) If and

are two topological spaces, we can define the product space

to be the Cartesian product

with the topology generated by the product sets

, where U and V are open in X and Y respectively. Observe that two functions

,

from a topological space Z are continuous if and only if the pairing

defined by $(f,g)(z) := (f(z),g(z))$ is continuous in the product topology, and also that the projection maps

and

are continuous (cf. Exercise 6).

We mention that not every topological space can be generated from a metric (such topological spaces are called metrisable). One important obstruction to this arises from the Hausdorff property:

Definition 6. A topological space X is said to be a Hausdorff space if for any two distinct points x, y in X, there exist disjoint neighbourhoods

of x and y respectively.

Example 16. Every metric space is Hausdorff (one can use the open balls and

as the separating neighbourhoods. On the other hand, the trivial topology (Example 7) on two or more points is not Hausdorff, and neither is the cocountable topology (Remark 3) on an uncountable set, or the upper topology (Example 13) on the real line. Thus, these topologies do not arise from a metric.

Exercise 10. Show that the half-open topology (Example 12) is Hausdorff, but does not arise from a metric. [Hint: assume for contradiction that the half-open topology did arise from a metric; then show that for every real number x there exists a rational number q and a positive integer n such that the ball of radius 1/n centred at q has infimum x.] Thus there are more obstructions to metrisability than just the Hausdorff property; a more complete answer is provided by Urysohn’s metrisation theorem, which we will cover in later notes.

Exercise 11. Show that in a Hausdorff space, any sequence can have at most one limit. (For a more precise statement, see Exercise 15 below.)

A homeomorphism (or topological isomorphism) between two topological spaces is a continuous invertible map whose inverse

is also continuous. Such a map identifies the topology on X with the topology on Y, and so any topological concept of X will be preserved by f to the corresponding topological concept of Y. For instance, X is compact if and only if Y is compact, X is Hausdorff if and only if Y is Hausdorff, x is adherent to E if and only if f(x) is adherent to f(E), and so forth. When there is a homeomorphism between two topological spaces, we say that X and Y are homeomorphic (or topologically isomorphic).

Example 14. The tangent function is a homeomorphism between and

(with the usual topologies), and thus preserves all topological structures on these two spaces. Note however that the former space is bounded as a metric space while the latter is not, and the latter is complete while the former is not. Thus metric properties such as boundedness or completeness are not purely topological properties, since they are not preserved by homeomorphisms.

— Nets (optional) —

A sequence in a space X can be viewed as a function from the natural numbers

to X. We can generalise this concept as follows.

Definition 7. A net in a space X is a tuple

, where

is a directed set (i.e. a pre-ordered set such that any two elements have at least one upper bound), and

for each

. We say that a statement

holds for sufficiently large

in a directed set A if there exists

such that

holds for all

. [Note in particular that if

and

separately hold for sufficiently large

, then their conjunction

also holds for sufficiently large

.]

A net

in a topological space X is said to converge to a limit

if for every neighbourhood V of x, we have

for all sufficiently large

.

A subnet of a net

is a tuple of the form

, where

is another directed set, and

is a monotone map (thus

whenever

) which is also has cofinal image, which means that for any

there exists

with

(in particular, if

is true for sufficiently large

, then

is true for sufficiently large

).

Remark 5. Every sequence is a net, but one can create nets that do not arise from sequences (in particular, one can take A to be uncountable). Note a subtlety in the definition of a subnet – we do not require to be injective, so B can in fact be larger than A! Thus subnets differ a little bit from subsequences in that they “allow repetitions”.

Remark 6. Given a directed set A, one can endow with the topology generated by the singleton sets

with

, together with the sets

for

, with the convention that

for all

. The property of being directed is precisely saying that these sets form a base. A net

converges to a limit

if and only if the function

is continuous on

(cf. Example 11). Also, if

is a subnet of

, then

is a continuous map from

to

, if we adopt the convention that

. In particular, a subnet of a convergent net remains convergent to the same limit.

The point of working with nets instead of sequences is that one no longer needs to worry about the distinction between sequential and non-sequential concepts in topology, as the following exercises show:

Exercise 12. Let X be a topological space, let E be a subset of X, and let x be an element of X. Show that x is an adherent point of E if and only if there exists a net in E that converges to x. (Hint: take A to be the directed set of neighbourhoods of x, ordered by reverse set inclusion.)

Exercise 13. Let be a map between two topological spaces. Show that f is continuous if and only if for every net

in X that converges to a limit x, the net

converges in Y to f(x).

Exercise 14. Let X be a topological space. Show that X is compact if and only if every net has a convergent subnet. (Hint: equate both properties of X with the finite intersection property, and review the proof of Theorem 1. Similarly, show that a subset E of X is relatively compact if and only if every net in E has a subnet that converges in X. (Note that as not every compact space is sequentially compact, this exercise shows that we cannot enforce injectivity of in the definition of a subnet.)

Exercise 15. Show that a space is Hausdorff if and only if every net has at most one limit.

Exercise 16. In the product space in Example 14, show that a net

converges in

to

if and only if for every

, the net

converges in Y to

.

[Update, Jan 31: Definition of subnet corrected; Exercise 8 corrected; Exercise 9 added, subsequent exercises renumbered; hint for Exercise 2 altered; some remarks added.]

49 comments

Comments feed for this article

30 January, 2009 at 1:26 pm

Franciscus Rebro

Hi Terry,

In Definition 1 did you mean to write the Cartesian product X x X rather than that first right arrow?

Thanks for the notes!

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

31 January, 2009 at 4:59 am

johan

The definition of homeomorphism seems to have been cut short, not mentioning the continuity of the inverse.

There is a latex error in point 10 of definition 5. [Corrected, thanks – T.]

31 January, 2009 at 9:15 pm

jzahl

I believe exercise 8 is not correct; compact -> limit point compact, but not sequentially compact: there exist (non-metrizable, non-second-countable) compact spaces that are not sequentially compact. I don’t have an example, but my claim is backed up by Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sequentially_compact_space .

31 January, 2009 at 10:17 pm

Terence Tao

Dear jzahl: Ack, you’re right, of course; I had confused limit point compact with sequentially compact as you had guessed. (I also was misled by incorrectly thinking that a subnet of a sequence was the same thing as a subsequence.) I think I fixed these issues now.

Dear anonymous: Huh, that is an annoying technicality. Fortunately, I think I can resolve it by rewording the hint slightly. (Note that the way I have defined metric completion, it is not necessary for the completed space to be formed by equivalence classes of Cauchy sequences of the original space, even though this is the canonical way to construct such a completion.)

31 January, 2009 at 9:43 pm

Anonymous

This is admittedly pedantic, but your comments about arising as the metric completion of

arising as the metric completion of  are pedagogically correct but technically problematic. The definition of metric completion rests ultimately on the definition of that of the metric space itself, and the definition of metric space requires a function

are pedagogically correct but technically problematic. The definition of metric completion rests ultimately on the definition of that of the metric space itself, and the definition of metric space requires a function  . So since the definition of a metric space already presupposes that we have the (nonnegative) reals, you can’t use metric completion to “construct”

. So since the definition of a metric space already presupposes that we have the (nonnegative) reals, you can’t use metric completion to “construct”  from

from  .

.

Of course, this is indeed the right way to think about what’s really going on with metric completion. How counterintuitive that the best way to explain this concept isn’t a proper example of metric completion, though…

2 February, 2009 at 6:30 am

K. P. Hart

Re completions: one can always go the Bourbaki way and define R to be the completion of the uniform(!) space Q (See Chapter IV in the first book of Topologie Generale).

For jzahl: the Cech-Stone compactification of N is compact (hence limit-point compact, aka countably compact) by not sequentially compact.

3 February, 2009 at 2:21 am

Tusarepides

Some further exposition (mathematical/philosophical/pedagogical) about uniform spaces and structures would be greatly appreciated (i.e. beyond the wiki entry). Please give me a clue as to where you might have written about this before (something tells me that you have).

3 February, 2009 at 2:58 pm

liuxiaochuan

It’s 245B. [Ack, not again – at any rate, corrected, thanks – T.]

15 March, 2017 at 11:08 am

Anonymous

The url still shows 254a-notes-8-a-quick-review-of-point-set-topology/

[The URL is unfortunately not editable – T.]

6 February, 2009 at 8:37 am

Anonymous

There’s an error in the definition of interior point:

” Given a set E, we say that x is an interior pointinterior of E if … ” [Corrected, thanks – T.]

6 February, 2009 at 9:58 am

Anonymous

Another small point: for the proof of (1 \Rightarrow 4) in Thm. 1 I dont think you need/have that d(x_{1},x_{n}) \to \infty. For example with the discrete metric on the integers. [Ack, yes, I was only proving the weaker statement here that unbounded sets are not compact. This has been corrected – T.]

6 February, 2009 at 1:13 pm

K. P. Hart

For Tusarepides: yes, indeed, I wrote a short introduction to Uniform Spaces; you can find it here; it appeared in the Encyclopedia of General Topology, which I co-edited. Hope it helps.

11 February, 2009 at 3:32 pm

245B, Notes 10: Compactness in topological spaces « What’s new

[…] from Notes 8 that a topological space is Hausdorff if every distinct pair of points can be separated by two […]

11 February, 2009 at 7:05 pm

Announcement « Liu Xiaochuan’s Weblog

[…] 14 of the Notes 8 of the course: Real Analysis:Let X be a topological space. Show that X is compact if and only if every net has a convergent […]

16 February, 2009 at 7:28 am

实分析0-10 « Liu Xiaochuan’s Weblog

[…] 第八节复习点集拓扑。我还算熟悉,基本上把精力都放在了ultrafilter出现的地方。,ultrafilter是我学到的一个很有趣的工具,以前写过一个介绍性的帖子。还应该提到的是“网”的概念。它是数列的一个加强版。以前常常会遇到,这回算是有了一个全面的了解了。值得注意的是,一个空间是紧致的等价于任意一个网都有收敛子网。这是区别于列紧性质的。 […]

10 March, 2009 at 1:24 pm

245B, Notes 11: The strong and weak topologies « What’s new

[…] subsequence has a further subsequence that converges a.e. to zero, and use Exercise 7′ from Notes 8.) Thus almost everywhere convergence is not “topologisable” in general. Exercise 9 […]

29 March, 2009 at 12:32 am

倡议 « Liu Xiaochuan’s Weblog

[…] 14 of the Notes 8 of the course: Real Analysis:Let X be a topological space. Show that X is compact if and only if every net has a convergent […]

27 August, 2009 at 9:53 pm

Anush Tserunyan

Dear Prof. Tao,

Maybe I’m confusing something, but I think the requirement of monotonicity in the definition of subnet is too strong. With this definition I fail to show that compact implies every net has a convergent subnet. I show that in a compact space every net has a cluster point but I cannot imply that then there is a subnet converging to that cluster point. However, if we require only that for every \alpha in A there is a \beta_0 in B such that for all \beta in B with \beta \geq \beta_0, \phi(\beta) \geq \alpha, then everything is fine.

Thanks

27 August, 2009 at 11:55 pm

Terence Tao

I think one can recover monotonicity by taking B not to be the set of neighbourhoods of the cluster point, but instead to be the set of all finite collections of neighbourhoods of the cluster point, ordered by set inclusion. One can build inductively to gain the monotonicity.

inductively to gain the monotonicity.

28 August, 2009 at 12:26 am

Anush Tserunyan

Oh right! Thank you so much!

11 December, 2009 at 1:44 am

Anonymous

Dear Prof. Tao,

if we have a complete, seperable metric space, what can we say about its cardinality?

thanks

8 July, 2010 at 10:48 pm

Kestutis Cesnavicius

Few typos:

1. In the first sentence of the proof of Theorem 1 “converging to n” should be “converging to x”. should be

should be  .

.

2. In definition 5.10 the last “in X” should be “in Y”.

3. In the Remark 6 on the upper topology I think the equivalence between continuity in the upper topology and the convergence of the net does not hold in general. E.g., in Example 11 we had the order topology which is finer than the upper topology; I guess for the equivalence the order topology is needed here as well.

4. In Exercise 16

9 July, 2010 at 9:21 am

Terence Tao

Thanks for the corrections! Regarding point 3, I think the upper topology is the correct one to use here (note that there is no reason why a net , convergent or otherwise, needs to be continuous with respect to the order topology).

, convergent or otherwise, needs to be continuous with respect to the order topology).

9 July, 2010 at 9:39 am

Kestutis Cesnavicius

Maybe then for the equivalence one requires the continuity of at $\infty$. I don’t see how one gets that the preimage of an open $U$ is open, if that $U$ happens to contain just one $x_{\alpha}$ (and in particular, does not contain $x_{\infty}$).

at $\infty$. I don’t see how one gets that the preimage of an open $U$ is open, if that $U$ happens to contain just one $x_{\alpha}$ (and in particular, does not contain $x_{\infty}$).

10 July, 2010 at 9:28 pm

Terence Tao

Ah, right. I intended the topology to be discrete away from infinity; I’ve modified the remark accordingly.

20 July, 2010 at 2:03 pm

Shawn

Hi!

I’m actually a bit confused about two things regarding subnets. Let’s take the example of \delta_n(g) = g(n) (the linear operator on l_infty which evaluates g at the point n on N, the natural numbers). Now clearly ||\delta_n||_* = 1 for all n and so there is a weak-* cluster point.

One can quickly see that there is no weakly convergent subsequence since if there were, we’d have g(n_k) -> F(g) and we can modify g as we wish on the points n_k.

By Banach Alaoglu, there is a weak-* convergent subnet. How do we construct such a subnet in this case? Why is it the case that if we have a convergent subnet that we can’t extract a convergent subsequence from that subnet? (ie. aren’t subnets ‘larger’ than subsequences in that they can be uncountable?)

Thanks!

20 July, 2010 at 2:42 pm

Terence Tao

To construct such a subnet requires the axiom of choice. For instance, one can select a non-principal ultrafilter p on the natural numbers, and then define to be the element of

to be the element of  given by

given by  (or, if one wishes,

(or, if one wishes,  is the evaluation of the Stone-Cech extension of f at p). One can then obtain a subnet of the

is the evaluation of the Stone-Cech extension of f at p). One can then obtain a subnet of the  converging to

converging to  by taking the index set of the net to be the space of finite collections of constraints of the form

by taking the index set of the net to be the space of finite collections of constraints of the form  or

or  for various choices of natural number

for various choices of natural number  ,

,  , and

, and  . From the properties of a non-principal ultrafilter, any finite collection of such constraints is satisfiable for some n, and this then gives the desired subnet.

. From the properties of a non-principal ultrafilter, any finite collection of such constraints is satisfiable for some n, and this then gives the desired subnet.

The reason why convergence of a subnet does not imply convergence of a subsequence is that the order structure on the subnet can be a lot sparser than the order structure on any associated subsequence, which makes convergence on the subnet a significantly weaker property. To converge on a subsequence, one must have stability on final segments of that subsequence, which is a significantly stronger condition than asking for stability on final segments of the subnet, because the pullback of a final segment from the subsequence to the subnet is a lot bigger than just one final segment of the subnet.

22 September, 2019 at 11:59 pm

Matthias Hübner

Isn’t here in

here in  i.e. in the dual of

i.e. in the dual of  ?

?

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

20 July, 2010 at 4:08 pm

Shawn

Thanks! I need some time to digest all that.

It’s really amazing that you find the time to respond to your reader’s questions. It’s greatly appreciated!

22 October, 2012 at 4:30 pm

Guillermo Rey

I’ve been trying to find a historial reference for Exercise 7′ but I couldn’t find much on google that isn’t written by you with the name “Urysohn’s subsequence principle” and related things. Do you have any information on the history of this principle?

Thanks.

22 October, 2012 at 5:11 pm

Terence Tao

I believe the original reference is

P. Urysohn, Sur les classes L de M. Frechet, Enseignement Math. 25 (1926), 77-83.

although I do not currently have access to this article.

22 October, 2012 at 5:21 pm

Guillermo Rey

Thank you!

9 May, 2013 at 2:03 am

anonymousCoward

Proof of Heine-Borel, in (!1 => !2) you didn’t close this parenthesis:

…(since otherwise one could easily construct…

21 November, 2014 at 4:41 pm

Jack

In this wikipedia article http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Directed_set (and also in Folland’s book), directed sets are defined as preordered set with the additional ”upper bound property”. In Definition 7 of this note, “partially ordered set” is used instead. Would this difference matter a lot?

[Not really, but pre-order is a slightly more convenient definition, and I’ve changed the notes to conform to this more common terminology. -T.]

28 September, 2015 at 6:34 am

Anonymous

In Douglas’s book Banach Algebra Techniques in Operator Theory, the author also uses “partially order” in the definition of directed sets. You said pre-order a “slightly more convenient” in the comment. Is it because one has one less axiom to check?

28 September, 2015 at 12:36 pm

Terence Tao

Yes, though more importantly, the deletion of that axiom allows the pullback of a directed set

of a directed set  by some surjective (or at least cofinal) map

by some surjective (or at least cofinal) map  to remain directed even if

to remain directed even if  is not injective, which can be convenient for some purposes.

is not injective, which can be convenient for some purposes.

28 February, 2015 at 5:53 am

jack

We have the word “generated” in topology and “span” in linear algebra. Given a vector space and a subset

and a subset  of

of  , the “span” of

, the “span” of  is a subspace of

is a subspace of  , but

, but  is not necessarily a basis for span(B). On the other hand, given a set

is not necessarily a basis for span(B). On the other hand, given a set  and a family

and a family  of subsets of

of subsets of  we always have

we always have  as a basis for the “generated” topology

as a basis for the “generated” topology  (generated by

(generated by  ). Why do we have such difference?

). Why do we have such difference?

28 February, 2015 at 9:43 am

Terence Tao

In general, is only a sub-base of

is only a sub-base of  , rather than a base. In the category of linear algebra, it is always possible (assuming the axiom of choice) to reduce a spanning set to a linearly independent set (and as such, the linear independence hypothesis is then included in the notion of a linear basis), but no such reduction is available in the topological category; the most useful reduction along these lines is to pass from a sub-base to a base (although this tends to make the base larger than then sub-base, rather than smaller).

, rather than a base. In the category of linear algebra, it is always possible (assuming the axiom of choice) to reduce a spanning set to a linearly independent set (and as such, the linear independence hypothesis is then included in the notion of a linear basis), but no such reduction is available in the topological category; the most useful reduction along these lines is to pass from a sub-base to a base (although this tends to make the base larger than then sub-base, rather than smaller).

Presumably a category-theoretic analysis of both the linear algebra category and the topological category would be able to pinpoint the difference here more precisely, but I am not an expert in these matters.

4 March, 2015 at 6:48 pm

Anonymous

In the assumption of Exercise 13, if one adds the assumption that is a bijection, can one replace “continuous” with “a homeomorphism” in the statement?

is a bijection, can one replace “continuous” with “a homeomorphism” in the statement?

[No; not all continuous bijections are homeomorphisms. It’s a good exercise to come up with a counterexample. -T.]

15 March, 2017 at 11:22 am

Anonymous

One should note that there are different versions of definitions for the concept “subnets”. And the one given in this post is “Willard subnet”, which implies the one (“Kelley subnet”) in Folland.

In practice of doing analysis, would such difference matter a lot? [No, not really. See e.g. http://thales.doa.fmph.uniba.sk/sleziak/texty/rozne/topo/subnets2.pdf -T.]

26 August, 2017 at 8:26 am

Anonymous

example 15 missing the direct sum notation (3 sentences from the end)

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

2 February, 2019 at 5:05 am

Matthias Hübner

In Example 12 (Half-open topology) it should be:

“for all sufficiently large $n$” ($n$ instead of $x$).

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

12 June, 2019 at 4:01 pm

Bernhard

I learned the theorem your call “Heine-Borel” as “Bolzano-Weierstrass”. Now, both seem wrong and correct in the sense that HB showed recoving compactness means bounded and closed (in R^n) and BW proved the equivalence of bounded and closed to sequential compactness. Maybe I will start calling it BBHW in future :)

30 November, 2019 at 6:11 am

Anonymous

There seem to be typos in the first sentence of Example 11.

[Corrected – T.]

30 November, 2019 at 6:13 am

Anonymous

What does the notation mean?

mean?

30 November, 2019 at 6:16 am

Anonymous

Also, in the following excerpt,

Also observe that a function from the extended natural numbers

from the extended natural numbers  (with the order topology) into a topological space

(with the order topology) into a topological space  is continuous if and only if

is continuous if and only if  as

as  , so one can interpret convergence of sequences as a special case of continuity.

, so one can interpret convergence of sequences as a special case of continuity.

I think you meant to say as ?

?

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

1 December, 2019 at 1:20 pm

Anonymous

Not sure if it is the problem of my chrome explorer or not.

I still see (literally) the following in the first sentence:

Any totally ordered set $(X, a \}$ and $\{ x \in X: x < a \}$ for all $a \in X$.

Perhaps you meant for any totally ordered set , the topology is generated by sets of the form

, the topology is generated by sets of the form  for all

for all  .

.

[Should be fixed now – T.>]

4 January, 2023 at 7:00 am

Anonymous

What is the point/intuition of the introduced notions of “rich” and “asymptotically rich” sets in the proof of Theorem 1? Can the proof be written and simplified without these two notions?

[You are welcome to come up with your own arrangement of the proof; this is often an instructive exercise. -T]

15 January, 2023 at 8:06 am

Anonymous

In Example 15, where continuity of functions from to

to  is characterized, if one switches the directions of the maps, it does not work anymore: in general, it is not true that

is characterized, if one switches the directions of the maps, it does not work anymore: in general, it is not true that  is continuous if and only if

is continuous if and only if  is continuous for each

is continuous for each  and

and  is continuous for each

is continuous for each  .

.

When tracing the proof, one thing that seems to be relevant for the contrast is that the inverse map commutes with both union and intersections while the forward map

commutes with both union and intersections while the forward map  does not commute with intersections.

does not commute with intersections.

Are there any “structural” reasons for this phenomenon?