LLet be a self-adjoint operator on a finite-dimensional Hilbert space

. The behaviour of this operator can be completely described by the spectral theorem for finite-dimensional self-adjoint operators (i.e. Hermitian matrices, when viewed in coordinates), which provides a sequence

of eigenvalues and an orthonormal basis

of eigenfunctions such that

for all

. In particular, given any function

on the spectrum

of

, one can then define the linear operator

by the formula

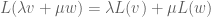

which then gives a functional calculus, in the sense that the map is a

-algebra isometric homomorphism from the algebra

of bounded continuous functions from

to

, to the algebra

of bounded linear operators on

. Thus, for instance, one can define heat operators

for

, Schrödinger operators

for

, resolvents

for

, and (if

is positive) wave operators

for

. These will be bounded operators (and, in the case of the Schrödinger and wave operators, unitary operators, and in the case of the heat operators with

positive, they will be contractions). Among other things, this functional calculus can then be used to solve differential equations such as the heat equation

The functional calculus can also be associated to a spectral measure. Indeed, for any vectors , there is a complex measure

on

with the property that

indeed, one can set to be the discrete measure on

defined by the formula

One can also view this complex measure as a coefficient

of a projection-valued measure on

, defined by setting

Finally, one can view as unitarily equivalent to a multiplication operator

on

, where

is the real-valued function

, and the intertwining map

is given by

so that .

It is an important fact in analysis that many of these above assertions extend to operators on an infinite-dimensional Hilbert space , so long as one one is careful about what “self-adjoint operator” means; these facts are collectively referred to as the spectral theorem. For instance, it turns out that most of the above claims have analogues for bounded self-adjoint operators

. However, in the theory of partial differential equations, one often needs to apply the spectral theorem to unbounded, densely defined linear operators

, which (initially, at least), are only defined on a dense subspace

of the Hilbert space

. A very typical situation arises when

is the square-integrable functions on some domain or manifold

(which may have a boundary or be otherwise “incomplete”), and

are the smooth compactly supported functions on

, and

is some linear differential operator. It is then of interest to obtain the spectral theorem for such operators, so that one build operators such as

or to solve equations such as (1), (2), (3), (4).

In order to do this, some necessary conditions on the densely defined operator must be imposed. The most obvious is that of symmetry, which asserts that

for all . In some applications, one also wants to impose positive definiteness, which asserts that

for all . These hypotheses are sufficient in the case when

is bounded, and in particular when

is finite dimensional. However, as it turns out, for unbounded operators these conditions are not, by themselves, enough to obtain a good spectral theory. For instance, one consequence of the spectral theorem should be that the resolvents

are well-defined for any strictly complex

, which by duality implies that the image of

should be dense in

. However, this can fail if one just assumes symmetry, or symmetry and positive definiteness. A well-known example occurs when

is the Hilbert space

,

is the space of test functions, and

is the one-dimensional Laplacian

. Then

is symmetric and positive, but the operator

does not have dense image for any complex

, since

for all test functions , as can be seen from a routine integration by parts. As such, the resolvent map is not everywhere uniquely defined. There is also a lack of uniqueness for the wave, heat, and Schrödinger equations for this operator (note that there are no spatial boundary conditions specified in these equations).

Another example occurs when ,

,

is the momentum operator

. Then the resolvent

can be uniquely defined for

in the upper half-plane, but not in the lower half-plane, due to the obstruction

for all test functions (note that the function

lies in

when

is in the lower half-plane). For related reasons, the translation operators

have a problem with either uniqueness or existence (depending on whether

is positive or negative), due to the unspecified boundary behaviour at the origin.

The key property that lets one avoid this bad behaviour is that of essential self-adjointness. Once is essentially self-adjoint, then spectral theorem becomes applicable again, leading to all the expected behaviour (e.g. existence and uniqueness for the various PDE given above).

Unfortunately, the concept of essential self-adjointness is defined rather abstractly, and is difficult to verify directly; unlike the symmetry condition (5) or the positive condition (6), it is not a “local” condition that can be easily verified just by testing on various inputs, but is instead a more “global” condition. In practice, to verify this property, one needs to invoke one of a number of a partial converses to the spectral theorem, which roughly speaking asserts that if at least one of the expected consequences of the spectral theorem is true for some symmetric densely defined operator

, then

is self-adjoint. Examples of “expected consequences” include:

- Existence of resolvents

(or equivalently, dense image for

);

- Existence of a contractive heat propagator semigroup

(in the positive case);

- Existence of a unitary Schrödinger propagator group

;

- Existence of a unitary wave propagator group

(in the positive case);

- Existence of a “reasonable” functional calculus.

- Unitary equivalence with a multiplication operator.

Thus, to actually verify essential self-adjointness of a differential operator, one typically has to first solve a PDE (such as the wave, Schrödinger, heat, or Helmholtz equation) by some non-spectral method (e.g. by a contraction mapping argument, or a perturbation argument based on an operator already known to be essentially self-adjoint). Once one can solve one of the PDEs, then one can apply one of the known converse spectral theorems to obtain essential self-adjointness, and then by the forward spectral theorem one can then solve all the other PDEs as well. But there is no getting out of that first step, which requires some input (typically of an ODE, PDE, or geometric nature) that is external to what abstract spectral theory can provide. For instance, if one wants to establish essential self-adjointness of the Laplace-Beltrami operator on a smooth Riemannian manifold

(using

as the domain space), it turns out (under reasonable regularity hypotheses) that essential self-adjointness is equivalent to geodesic completeness of the manifold, which is a global ODE condition rather than a local one: one needs geodesics to continue indefinitely in order to be able to (unitarily) solve PDEs such as the wave equation, which in turn leads to essential self-adjointness. (Note that the domains

and

in the previous examples were not geodesically complete.) For this reason, essential self-adjointness of a differential operator is sometimes referred to as quantum completeness (with the completeness of the associated Hamilton-Jacobi flow then being the analogous classical completeness).

In these notes, I wanted to record (mostly for my own benefit) the forward and converse spectral theorems, and to verify essential self-adjointness of the Laplace-Beltrami operator on geodesically complete manifolds. This is extremely standard analysis (covered, for instance, in the texts of Reed and Simon), but I wanted to write it down myself to make sure that I really understood this foundational material properly.

— 1. Self-adjointness and resolvents —

To begin, we study what we can abstractly say about a densely defined symmetric linear operator on a Hilbert space

. To avoid some technical issues we shall assume that the Hilbert space is separable, which is the case typically encountered in applications (particularly in PDE). We will occasionally assume also that

is positive, but will make this hypothesis explicit whenever we are doing so.

All convergence in Hilbert spaces will be in the strong (i.e. norm) topology unless otherwise stated. Similarly, all inner products and norms will be over unless otherwise stated.

For technical reasons, it is convenient to reduce to the case when is closed, which means that the graph

is a closed subspace of

. Equivalently,

is closed if whenever

is a sequence converging strongly to a limit

, and

converges to a limit

in

, then

and

. For instance, thanks to the closed graph theorem, an everywhere-defined linear operator is closed if and only if it is bounded.

Not every densely defined symmetric linear operator is closed (indeed, one could take a closed operator and restrict the domain of definition to a proper dense subspace). However, all such operators are closable, in that they have a closure:

Lemma 1 (Closure) Let

be a densely defined symmetric linear operator. Then there exists a unique extension

of

as a closed, densely defined symmetric linear operator, such that the graph

of

is the closure of the graph

of

.

Proof: The key step is to show that the closure of the graph of

remains a graph, i.e. it obeys the vertical line test. If this failed, then by linearity one could find a sequence

converging to zero such that

converged to a non-zero limit

. Since

is dense, we can find

such that

. But then by symmetry

On the other hand, as ,

. Thus

is the graph of some function

. It is easy to see that this is a densely defined symmetric linear operator extending

, and is the unique such operator.

Exercise 1 Show that

is positive if and only if

is positive.

Remark 1 We caution that

is not the closure or completion of

with respect to the usual norm

on

. (Indeed, as

is a dense subspace of

, that completion of

is simply

.) However, it is the completion of

with respect to the modified norm

.

In PDE applications, the closure tends to be defined on a Sobolev space of functions that behave well at the boundary, and is given by a distributional derivative. Here is a simple example of this:

Exercise 2 Let

be the Laplacian

, defined on the dense subspace

of

. Show that the closure

is defined on the Sobolev space

, defined as the completion of

under the Sobolev norm

and that the action of

is given by the weak (distributional) derivative,

.

Next, we define the adjoint of

, which informally speaking is the maximally defined operator for which one has the relationship

for and

. More formally, define

to be the set of all vectors

for which the map

is a bounded linear functional on

, which thus extends to the closure

of

. For such

, we may apply the Riesz representation theorem for Hilbert spaces and locate a unique vector

for which (7) holds. This is easily seen to define a linear operator

. Furthermore, the claim that

is symmetric can be reformulated as the claim that

extends

.

If is not symmetric, then

does not extend

, and need not be densely defined at all. However, it is still closed:

Exercise 3 Let

be a densely defined linear operator, and let

be its adjoint. Show that

is the orthogonal complement in

of (the closure of)

. Conclude that

is always closed.

If

is symmetric, show that

and

.

Exercise 4 Construct an example of a densely defined linear operator

in a separable Hilbert space

for which

is only defined at

. (Hint: Build a dense linearly independent basis of

, let

be the algebraic span of that basis, and design

so that the graph of

is dense in

.)

We caution that the adjoint of a symmetric densely defined operator

need not be itself symmetric, despite extending the symmetric operator

:

Exercise 5 We continue Example 2. Show that for any complex number

, the functions

lie in

with

. Deduce that

is not symmetric, and not positive.

Intuitively, the problem here is that the domain of is too “small” (it stays too far away from the boundary), which makes the domain of

too “large” (it contains too much stuff coming from the boundary), which ruins the integration by parts argument that gives symmetry.

Now we can define (essential) self-adjointness.

Definition 2 Let

be a densely defined linear operator.

is self-adjoint if

. (Note that this implies in particular that

is symmetric and closed.)

is essentially self-adjoint if it is symmetric, and its closure

is self-adjoint.

Note that this extends the usual definition of self-adjointness for bounded operators. Conversely, from the closed graph theorem we also observe the Hellinger-Toeplitz theorem: an operator that is self-adjoint and everywhere defined, is necessarily bounded.

Exercise 6 Let

be a densely defined symmetric closed linear operator. Show that

is self-adjoint if and only if

is symmetric.

It is not immediately obvious what advantage self-adjointness gives. To see this, we consider the problem of inverting the operator for some complex number

, where

is densely defined, symmetric, and closed. Observe that if

, then

is necessarily real. In particular,

and hence by the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality

In particular, if is strictly complex (i.e. not real), then

is injective. Furthermore, we see that if

is such that

is convergent, then by (8)

is convergent also, and hence

is convergent. As

was assumed to be closed, we conclude that

converges to a limit

in

, and

converges to

. As a consequence, we see that the space

is a closed subspace of

. From (8) we then see that we can define an inverse

of

, which we call the resolvent of

with spectral parameter

; this is a bounded linear operator with norm

.

Exercise 7 If

is densely defined, symmetric, closed, and positive, and

is a complex number with

, show

is well-defined on

with

.

Now we observe a connection between self-adjointness and the domain of the resolvent. We first need some basic properties of the resolvent:

Exercise 8 Let

be densely defined, symmetric, and closed.

- (i) (Resolvent identity) If

are distinct strictly complex numbers with

everywhere defined, show that

. (Hint: compute

two different ways.)

- (ii) If

is a strictly complex number with

and

everywhere defined, show that

.

Proposition 3 Let

be densely defined, symmetric, and closed, let

be the adjoint, and let

be strictly complex.

- (i) (Surjectivity is dual to injectivity)

is everywhere defined if and only if the operator

has trivial kernel.

- (ii) (Self-adjointness implies surjectivity) If

is self-adjoint, then

is everywhere defined.

- (iii) (Surjectivity implies self-adjointness) Conversely, if

and

are both everywhere defined, then

is self-adjoint.

In particular, we see that we have a criterion for self-adjointness: a densely defined symmetric closed operator is self-adjoint if and only if and

are both everywhere defined, or in other words if

and

are both surjective.

Proof: We first prove (i). If is not everywhere defined, then the closed subspace

is not all of

. Thus there must be a non-zero vector

in the orthogonal complement of this subspace, thus

for all

. In particular,

and hence, by definition of ,

lies in

. Now from (7) we have

for all ; since

is dense, we have

as required. The converse implication follows by reversing these steps.

Now we prove (ii). Suppose that was not everywhere defined. By (i) and self-adjointness, we conclude that

for some non-zero

. But this contradicts (8).

Now we prove (iii). Let ; our task is to show that

. From Exercise 8(ii) and (7) one has

for all . We conclude that

. Since

takes values in

, the claim follows.

Exercise 9 Let

be densely defined, symmetric, and closed, and let

be strictly complex.

- (i) If

is everywhere defined, show that

is everywhere defined whenever

. (Hint: use Neumann series.)

- (ii) If

is everywhere defined, show that

is everywhere defined whenever

has the same sign as

.

- (iii) If

is positive, and

is not a non-negative real, show that

is everywhere defined if and only if

is self-adjoint.

As a particular corollary of the above exercise, we see that a densely defined, symmetric closed positive operator is self-adjoint if and only if

is everywhere defined, or in other words if

is surjective.

Exercise 10 Let

be a measure space with a countably generated

-algebra (so that

is separable), let

be a measurable function, and let

be the space of all

such that

. Show that the multiplier operator

defined by

is a densely defined self-adjoint operator.

Exercise 11 Let

,

, and

is the momentum operator

. Show that

is densely defined and symmetric, and

is everywhere defined, but

is only defined on the orthogonal complement of

. (Here, we define the resolvent of a closable operator to be the resolvent of its closure.) In particular,

is not self-adjoint.

Exercise 12 Let

be densely defined and symmetric.

- (i) Show that

is essentially self-adjoint if and only if

and

are dense in

.

- (ii) If

is positive, show that

is essentially self-adjoint if and only if

is dense in

.

Exercise 13 Let

and

be sequences of real numbers, with the

all non-zero. Define the Jacobi operator

from the space

of compactly supported sequences

to the space

of square-summable sequences

by the formula

with the convention that

vanishes for

.

- (i) Show that

is densely defined and symmetric.

- (ii) Show that

is essentially self-adjoint if and only if the (unique) solution

to the recurrence

with

(and the convention

), is not square-summable.

This exercise shows that the self-adjointness of an operator, even one as explicit as a Jacobi operator, can depend in a rather subtle and “global” fashion on the behaviour of the coefficients of that oeprator.

— 2. Self-adjointness and spectral measure —

We have seen that self-adjoint operators have everywhere-defined resolvents for all strictly complex

. Now we use this fact to build spectral measures. We will need a useful tool from complex analysis, which places a one-to-one correspondence between finite non-negative measures on

and certain analytic functions on the upper half-plane:

Theorem 4 (Herglotz representation theorem) Let

be an analytic function from the upper half-plane

to the closed upper half-plane

, obeying a bound of the form

for all

and some

. Then there exists a finite non-negative Radon measure

on

such that

We set the proof of the above theorem as an exercise below. Note in the converse direction that if is a finite non-negative Radon measure, then the function

defined by (9) obeys all the hypotheses of the theorem. The Herglotz representation theorem, like the more well known Riesz representation theorem for measures, is a useful tool to construct non-negative Radon measures; later on we will also use Bochner’s theorem for a similar purpose.

Exercise 14 Let

be as in the hypothesis of the Herglotz representation theorem. For each

, let

be the function

.

- (i) Show that one has

for all

, where

is the Poisson kernel and

is the usual convolution operation.

- (ii) Show that the non-negative measures

have a finite mass independent of

, and converge in the vague topology as

to a non-negative finite measure

.

- (iii) Prove the Herglotz representation theorem.

Now we return to spectral theory. Let be a densely-defined self-adjoint operator, and let

. We consider the function

on the upper half-plane. We can use this function and the Herglotz representation theorem to construct spectral measures :

Exercise 15 Let

,

, and

be as above.

- (i) Show that

is analytic. (Hint: use Neumann series and Morera’s theorem.)

- (ii) Show that

for all

in the upper half-plane.

- (iii) Show that

for all

in the upper half-plane. (Hint: You will find Exercise 8 to be useful.)

- (iv) Show that

for all

. (Hint: first show this for

, writing

for some

.)

- (v) Show that there is a non-negative Radon measure

of total mass

such that

for all

in either the upper or lower half-plane.

- (vi) If

is positive, show that

is supported in the right half-line

.

We can depolarise these measures by defining

to obtain complex measures for any

such that

for all in either the upper or lower half-plane. From duality we see that this uniquely defines

. In particular,

depends sesquilinearly on

, and

. Also, since each

has mass

, we see that the inner product

can be recovered from the spectral measure

:

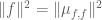

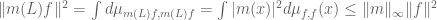

Exercise 16 With the above notation and assumptions, establish the bound

for all

. In particular, for any bounded Borel-measurable function

, there exists a unique bounded operator

such that

Thus, for instance is the identity when

, and

when

.

We have just created a map from the bounded Borel-measurable functions

on

, to the bounded operators

on

. Now we verify some basic properties of this map.

Exercise 17 (Bounded functional calculus) Let

be a self-adjoint densely defined operator, and let

be as above.

- (i) Show that the map

is

-linear. In particular, if

is real-valued, then

is self-adjoint.

- (ii) For any

and any strictly complex

, show that

. (Hint: use the resolvent identity.)

- (iii) For any

and any

, show that

.

- (iv) Show that the map

is a

-homomorphism. In particular,

and

commute for all

.

- (v) Show that

for all

. Improve the

to

. (Hint: to get this improvement, use the

identity

and the tensor power trick.)

- (vi) For any Borel subset

of

, show that

is an orthogonal projection of

. Show that

is a countably additive projection-valued measure, thus

for any sequence of disjoint Borel

, where the convergence is in the strong operator topology.

- (vii) For any bounded Borel set

, show that the image of

lies in

.

- (viii) Show that for any

and

, one has

.

- (ix) Let

be the union of the images of

for

. Show that

is a dense subspace of

(and hence of

), and that

maps

to

.

- (x) Show that

is the space of all functions

such that

. Conclude in particular that

maps

to

for all

.

- (xi) If

is such that

for all

, show that

takes values in

, that

for all

, and

for all

.

- (xii) Let

be the space of all

such that

is not invertible. Show that

is a closed set which is the union of the supports of the

as

range over

. In particular,

, and

when

is positive. Show that

is the identity map.

- (xiii) Extend the bounded functional calculus from the bounded Borel measurable functions

on

to the bounded measurable functions

on the spectrum

(i.e. show that the previous statements (i)-(xi) continue to hold after

is replaced by

throughout).

The above collection of facts (or various subcollections thereof) is often referred to as the spectral theorem. It is stated for self-adjoint operators, but one can of course generalise the spectral theorem to essentially self-adjoint operators by applying the spectral theorem to the closure. (One has to replace the domain of

by the domain

of the closure

, of course, when doing so.)

Exercise 18 (Spectral measure and eigenfunctions) Let the notation be as in the preceding exercise, and let

. Show that the space

is the range of the projection

. In particular,

has an eigenfunction at

if and only if

is non-trivial.

We have seen how the existence of resolvents gives us a bounded functional calculus (i.e. the conclusions in the above exercise). Conversely, if a symmetric densely defined closed operator has a bounded functional calculus, one can define the resolvents

simply as

, where

. Thus we see that the existence of a bounded functional calculus is equivalent to the existence of resolvents, which by the previous discussion is equivalent to self-adjointness.

Using the bounded functional calculus, one can not only recover the resolvents , but can now also build Schrödinger propagators

, and when

is positive definite one can also build heat operators

for

and wave operators

for

(and also define resolvents

for negative choices

of the spectral parameter). We will study these operators more in the next section.

Exercise 19 (Locally bounded functional calculus) Let

be a densely defined self-adjoint operator, and let

be the space of Borel-measurable functions from

to

which are bounded on every bounded set.

- Show that for every

there is a unique linear operator

such that

whenever

.

- (i) Show that the map

is a

-homomorphism.

- (ii) Show that when

is actually bounded (rather than merely locally bounded), then this definition of

agrees with that in the preceding exercise (after restricting from

to

).

- (iii) Show that

, where

is the identity map

.

- (iv) State and prove a rigorous version of the formal assertion that

and more generally

Now we use the spectral theorem to place self-adjoint operators in a normal form. Let us say that two operators and

are unitarily equivalent if there is a unitary map

with

and

. It is easy to see that all the constructions given above (such as the bounded functional calculus) are preserved by unitary equivalence.

If is a densely defined self-adjoint operator, define an invariant subspace to be a subspace

of

such that

for all

. We say that a vector

is a cyclic vector for

if the set

is dense in

.

Exercise 20

- (i) Show that if

is an invariant subspace of

, then so is

, and furthermore the orthogonal projections to

and

commute with

for every

.

- (ii) Show that if

is a invariant subspace of

, then the restriction

of

to

is a densely defined self-adjoint operator on

with

. Furthermore, one has

for all

.

- (iii) Show that

decomposes as a direct sum

, where the index set

is at most countable, and each

is a closed invariant subspace of

(with the

mutually orthogonal), such that each

has a cyclic vector

. (Hint: use Zorn’s lemma and the separability of

.)

- (iv) If

has a cyclic vector

, show that

is unitarily conjugate to a multiplication operator

on

for some non-negative Radon measure

, defined on the domain

.

- (v) For general

, show that

is unitarily conjugate to a multiplication operator

on

for some measure space

with a countably generated

-algebra and some measurable

, defined on the domain

.

The above exercise gives a satisfactory concrete description of a self-adjoint operator (up to unitary equivalence) as a multiplication operator on some measure space , although we caution that this equivalence is not canonical (there is some flexibility in the choice of the underlying measure space

and multiplier

, as well as the unitary conjugation map).

Exercise 21 Let

be a self-adjoint densely defined operator.

- (i) Show that

is positive if and only if

.

- (ii) Show that

is bounded if and only if

is bounded. Furthermore, in this case we have

.

- (iii) Show that

is trivial if and only if

is empty.

— 3. Self-adjointness and flows —

Now we relate self-adjointness to a variety of flows, beginning with the heat flow.

Exercise 22 Let

be a self-adjoint positive densely defined operator, and for each

, let

be the heat operator

.

- (i) Show that for each

,

is a bounded self-adjoint operator of norm at most

, that the map

is continuous in the strong operator topology, and such that

and

for all

. (The latter two properties are asserting that

is a one-parameter semigroup.)

- (ii) Show that for any

,

converges to

as

.

- (iii) Conversely, if

is not in

, show that

does not converge as

.

We remark that the above exercise can be viewed as a special case of the Hille-Yoshida theorem.

We now establish a converse to the above statement:

Theorem 5 Let

be a separable Hilbert space, and suppose one has a family

of bounded self-adjoint operators of norm at most

for each

, which is continuous in the strong operator topology, and such that

and

for all

. Then there exists a unique self-adjoint positive densely defined operator

such that

for all

.

We leave the proof of this result to the exercise below. The basic idea is to somehow use the identity

which suggests that

which should allow one to recover from the

.

Exercise 23 Let the notation be as in the above theorem.

- (i) Establish the uniqueness claim. (Hint: use Exercise 22.)

- (ii) Let

be the operator

Show that

is well-defined, bounded, positive semidefinite, and self-adjoint, with operator norm at most one, and that

commutes with all the

.

- (iii) Show that the spectrum of

lies in

, but that

has no eigenvalue at

.

- (iv) Show that there exists a densely defined self-adjoint operator

such that

is the identity on

and

is the identity on

.

- (v) Show that

is densely defined self-adjoint and positive definite, and commutes with all the

.

- (vi) Show that for all

and

, one has

and

, where the derivatives are in the classical limiting Newton quotient sense (in the strong topology of

).

- (vii) Conclude the proof of Theorem 5. (Hint: show that

is non-positive.)

The above exercise gives an important way to establish essential self-adjointness, namely by solving the heat equation (1):

Exercise 24 Let

be a densely defined symmetric positive definite operator. Suppose that for every

there exists a continuously differentiable solution

to (1). Show that

is essentially self-adjoint. (Hint: by investigating

, establish the uniqueness of solutions to the heat equation, which allows one to define linear contractions

. To establish self-adjointness of the

, take an inner product of a solution to the heat equation against a time-reversed solution to the heat equation, and differentiate that inner product in time. Now apply the preceding exercises to obtain a self-adjoint extension

of

. To show that

is the closure of

, it suffices to show that

is dense in

with the inner product

. But if

is not dense in

, then it has a non-trivial orthogonal complement; apply

to this complement to show that

also has a non-trivial orthogonal complement in

, a contradiction.)

Remark 2 When applying the above criterion for essential self-adjointness, one usually cannot use the space

of compactly supported smooth functions as the dense subspace, because this space is usually not preserved by the heat flow. However, in practice one can get around this by enlarging the class, for instance to the class of Schwartz functions.

Now we obtain analogous results for the Schrödinger propagators . We begin with the analogue of Exercise 22:

Exercise 25 Let

be a self-adjoint densely defined operator, and for each

, let

be the Schrödinger operator

.

- (i) Show that for each

,

is a unitary operator, that the map

is continuous in the strong operator topology, and such that

and

for all

.

- (ii) Show that for any

,

converges to

as

.

- (iii) Conversely, if

is not in

, show that

does not converge as

.

Now we can give the converse, known as Stone’s theorem on one-parameter unitary groups:

Theorem 6 (Stone’s theorem) Let

be a separable Hilbert space, and suppose one has a family

of unitary for each

, which is continuous in the strong operator topology, and such that

and

for all

. Then there exists a unique self-adjoint densely defined operator

such that

for all

.

We outline a proof of this theorem in an exercise below, based on using the group to build spectral measure.

Exercise 26 Let the notation be as in the above theorem.

- (i) Establish the uniqueness component of Stone’s theorem.

- (ii) Show that for any

, there is a non-negative Radon measure

of total mass

such that

for all

. (Hint: use Bochner’s theorem, a proof of which (at least on

, which is the case of interest here) can be found for instance in these notes.)

- (iii) Show that for any

, there is a unique complex measure

such that

for all

. Show that

is sesquilinear in

with

.

- (iv) Show that for any

, there is a unique bounded operator

such that

for all

.

- (v) Show that

for all

and

.

- (vi) Show that the map

is a *-homomorphism from

to

.

- (vii) Show that there is a projection-valued measure

with

, such that for every

, the complex measure

is such that

for all

.

- (viii) Show that there exists a self-adjoint densely defined operator

whose spectral measure is

.

- (ix) Conclude the proof of Stone’s theorem.

Exercise 27 Let

be a densely defined symmetric operator. Suppose that for every

there exists a continuously differentiable solution

to (2). Show that

is essentially self-adjoint.

We can now see a clear link between essential self-adjointness and completeness, at least in the case of scalar first-order differential operators:

Exercise 28 Let

be a smooth manifold with a smooth measure

, and let

be a smooth vector field on

which is divergence-free with respect to the measure

. Suppose that the vector field

is complete in the sense that for any

, there exists a global smooth solution

to the ODE

with initial data

. Show that the first-order differential operator

is essentially self-adjoint.

Extend the above result to non-divergence-free vector fields, after replacing

with

.

Remark 3 The requirement of completeness is basically necessary; one can still have essential self-adjointness if there are a measure zero set of initial data

for which the trajectories of

are incomplete, but once a positive measure set of trajectories become incomplete, the propagators

do not make sense globally, and so self-adjointness should fail.

Finally, we turn to the relationship between self-adjointness and the wave equation, which is a more complicated variant of the relationship between self-adjointness and the Schrödinger equation. More precisely, we will show the following version of Exercise 27:

Theorem 7 Let

be a densely defined positive symmetric operator. Suppose for every

, there exists a twice continuously differentiable (in

) solution

to (3). Then

is essentially self-adjoint.

(One could also obtain wave equation analogues of Exercise 25 or Theorem 6, but these are somewhat messy to state, and we will not do so here.)

We now prove this theorem. To simplify the exposition, we will assume that is strictly positive, in the sense that

for all non-zero

, and leave the general case as an exercise.

We introduce a new inner product on

by the formula

By hypothesis, this is a Hermitian inner product on . We then define an inner product

on

by the formula

then this is a Hermitian inner product on . We define the energy space

be the completion of

with respect to this inner product; we can factor this as

, where

is the completion of

using the

inner product.

Suppose is a twice continuously differentiable solution to (3) for some

. Then if we define the energy

then one easily computes using (3) that , and so

In particular, if , then

, and so twice continuously differentiable solutions to (3) are unique. This allows us to define wave operators

by defining

. This is clearly linear, and from the energy identity we see that

is an isometry, and thus extends to an isometry on the energy space

. From uniqueness we also see that

is a one-parameter group, i.e. a homomorphism that is continuous in the strong operator topology. In particular, the isometries

are invertible and are thus unitary. By Stone’s theorem, there thus exists a densely defined self-adjoint operator

on some dense subspace

of

such that

for all

.

If , then from the twice differentiability of the solution

to the wave equation, we see that

From Exercise 2, we conclude that and

Now we need to pass from the self-adjointness of to the essential self-adjointness of

. Suppose for contradiction that

was not essentially self-adjoint. Then

does not have dense image, and so there exists a non-zero

such that

for all .

It will be convenient to work with a “band-limited” portion of , to get around the problem that

and

can leave this domain. Let

be a compactly supported even smooth function of total mass one. For any

, define the Littlewood-Paley projection

where is the Schwartz function

. Then (by strong continuity of

) these operators map

to

, commutes with the entire functional calculus of

, and also maps

to

. Also, from functional calculus one sees that

and in particular maps

to

as well.

Let be the reflection operator

. From time reversal of the wave equation, we have

, and thus

commutes with

. In particular, we can write

for some operators and

. Since

preserves

, the operators

preserve

.

For any , we have

combining this with (12) we see that

and

for all . Also, since

preserves

, we see that

preserves

.

We can then expand as

and thus

In particular

for all . By duality (noting that

is a bounded real function of

) we conclude that

But by sending and using the spectral theorem, this implies from monotone convergence that the spectral measure

is zero, and thus

vanishes in

, a contradiction. This establishes the essential self-adjointness of

.

Exercise 29 Establish Theorem 7 without the assumption that

is strictly positive. (Hint: use the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality to show that strict positivity is equivalent to the absence of eigenfunctions with eigenvalue zero, and then quotient out such eigenfunctions.)

— 4. Essential self-adjointness of the Laplace-Beltrami operator —

We now discuss how one can use the above criteria to establish essential self-adjointness of a Laplace-Beltrami operator on a smooth complete Riemannian manifold

, viewed as a densely defined symmetric positive operator on the dense subspace

of

. This result was first established by Gaffney and by Roelcke.

To do this, we have to solve a PDE – either the Helmholtz equation (4) (for some not on the positive real axis), the heat equation (1), the Schrödinger equation (25), or the wave equation (3).

The Schrödinger formalism is quite suggestive. From a semiclassical perspective, the Schrödinger equation associated to the Laplace-Beltrami operator should be viewed as a quantum version of the classical flow associated to the corresponding Hamiltonian

, i.e. geodesic flow. From Exercise 28 we know that the generator of Hamiltonian flows (normalised by

) are essentially self-adjoint when they are complete (note from Liouville’s theorem that such generators are automatically divergence-free with respect to Liouville measure), which suggests that the Schrödinger operator

should be also. Unfortunately, this is not a rigorous argument, and is difficult to make it so due to the nature of the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, which has infinite speed of propagation, and no dissipative properties. In practice, we therefore establish esssential self-adjointness by solving one of the other equations.

To solve any of these equations, it is difficult to solve any of them by an exact formula (unless the manifold is extremely symmetric); but one can proceed by solving them approximately, and using perturbation theory to eliminate the error. This method works as long as the error created by the approximate solution is both sufficiently small and sufficiently smooth that perturbative techniques (such as Neumann series, or the inverse function theorem) become applicable. (This type of method, for instance, is used to deduce essential self-adjointness of various perturbations

of the Laplace-Beltrami operator from the essential self-adjointness of the original operator

.)

For instance, suppose one is trying to solve the Helmholtz equation

for some large real , and some

. For sake of concreteness let us take

to be three-dimensional. If

was a Euclidean space

, then we have an explicit formula

for the solution; note that the exponential decay of will keep

in

as well. Inspired by this, we can try to solve the Helmholtz equation in curved space by proposing as an approximate solution

This is a little problematic because develops singularities after a certain point, but if one has a uniform lower bound on the injectivity radius (here we are implicitly using the hypothesis of completeness), and also uniform bounds on the curvature and its derivatives, one can truncate this approximate solution to the region where

is small, and obtain an approximate solution

whose error

can be made to be smaller in norm than that of

if the spectral parameter

is chosen large enough; we omit the details. From this, we can then solve the Helmholtz equation by Neumann series and thus establish essential self-adjointness. A similar method also works (under the same hypotheses on

) to construct approximate heat kernels, giving another way to establish essential self-adjointness of the Laplace-Beltrami operator.

What about when there is no uniform bound on the geometry? In that case, it is best to work with the wave equation formalism, because the finite speed of propagation property of that equation allows one to localise to compact portions of the manifold for which uniform bounds on the geometry are automatic. Indeed, to solve the wave equation in for some fixed period of time, one can use finite speed of propagation, combined with completeness of the manifold, to work in a compact subset of this manifold, which by suitable alteration of the metric beyond the support of the solution, one can view as a subset of a compact complete manifold. On such manifolds, we already know essential self-adjointness by the previous arguments, so we may solve the wave equation in that setting (one can also solve the wave equation using methods from microlocal analysis, if desired), and then take repeated advantage of finite speed of propagation (which can be proven rigorously by energy methods) to glue together these local solutions to obtain a global solution; we omit the details.

In all these cases, a somewhat nontrivial application of PDE theory is required. Unfortunately, this seems to be inevitable; at some point one must somehow use the hypothesis of completeness of the underlying manifold, and PDE methods are the only known way to connect that hypothesis to the dynamics of the Laplace-Beltrami operator.

25 comments

Comments feed for this article

20 December, 2011 at 6:14 pm

Guest

No need to publish this, just a small correction on Exercise 23:

“To establish self-adjointness of the s(t) , take an inner product of a solution to the heat equation against a time-reversed solution OF the heat equation, and differentiate that inner product in time.”

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

21 December, 2011 at 11:59 am

Lior Silberman

Question: In the definition of adjoint just before Ex 3, it’s not clear to me why contains non-zero vectors at all, let alone why the adjoint is also a densely defined operator. If $L$ is symmetric then obviously

contains non-zero vectors at all, let alone why the adjoint is also a densely defined operator. If $L$ is symmetric then obviously  — what happens in general?

— what happens in general?

Typos:

Pf of Lemma 1: last \neq should be a \to , not equal to it. Later, the non-zero vector should be

, not equal to it. Later, the non-zero vector should be  .

. be multiplication by the complex conjugate? [i.e. did you mean for the function to be real valued?]

be multiplication by the complex conjugate? [i.e. did you mean for the function to be real valued?]

Statement of Prop 3(i): R(z) is everywhere defined iff the kernel is trivial.

Pf of Prop 3(i): In the second inline equation, the subspace is contained in

Ex 9: Isn’t the adjoint of multiplication by

Ex 17: missing closing parenthesis at the end.

[Corrected, thanks. In general, the adjoint could well be trivial; I added an exercise to this effect. – T.]

2 January, 2012 at 3:09 am

Александр Шапошников

It seems to me there is a missprint in Exercise 11:

R(i) and R(-i) should be interchanged

[Corrected, thanks – T]

3 January, 2012 at 12:08 pm

Александр Шапошников

There is another small missprint in Exercise 17 should be replaced with

should be replaced with

(item (x)):

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

19 May, 2012 at 11:35 am

Anonymous

I would like to suggest a minor improvement to Exercise 11. The operator given there is not closed, but the previous text defines the resolvent only in the closed case. This can be a little confusing to the beginner and I suggest that a little note might be added to make explicit that the resolvent of a closable operator is assumed to be the resolvent of the closure. Thank you.

[Suggestion implemented, thanks – T.]

16 September, 2014 at 8:04 am

VMT

Hi! I don’t understand the hint for ex 17.(v): using the fact that and ex 17.(iii) we directly obtain

and ex 17.(iii) we directly obtain  , which already implies

, which already implies  .

.

If this is correct, what did you have in mind when you wrote the hint?

(Sorry for posting a doubt about a 3 years-old entry..)

16 September, 2014 at 8:39 am

Terence Tao

Oh, that’s a nice solution! My solution proceeded by bounding instead, and the depolarisation identity can cost one a factor of 4 or so when one uses that route, if one isn’t being careful. (I’m also very fond of the tensor power trick, so I couldn’t resist an opportunity to sneak it in, even if as it turns out it can be done without in this case.)

instead, and the depolarisation identity can cost one a factor of 4 or so when one uses that route, if one isn’t being careful. (I’m also very fond of the tensor power trick, so I couldn’t resist an opportunity to sneak it in, even if as it turns out it can be done without in this case.)

16 September, 2014 at 9:23 am

VMT

Thank you; so you probably proceeded by bounding in terms of

in terms of  . Still, I don’t understand how one can use the depolarisation identity.. On the other hand, if you use Cauchy-Schwarz you get

. Still, I don’t understand how one can use the depolarisation identity.. On the other hand, if you use Cauchy-Schwarz you get  .

.

If the answer is complicated, never mind!

16 September, 2014 at 9:52 am

Terence Tao

Depolarisation gives a bound of the form which one can then amplify to

which one can then amplify to  by using homogeneity, as in this previous post. But it is true that by using the abstract Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, one can pass directly to

by using homogeneity, as in this previous post. But it is true that by using the abstract Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, one can pass directly to  .

.

16 September, 2014 at 10:03 am

VMT

Ah, now I see. Very instructive, thank you!

28 June, 2018 at 6:25 am

Jack

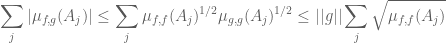

Hi, Sorry to comment on and old comment of a relatively old post. I am a bit stuck trying to show that directly using Cauchy-Schwarz (CS). It is a consequence of CS that for any measurable subset

directly using Cauchy-Schwarz (CS). It is a consequence of CS that for any measurable subset  ,

,  .

. is a finite partition of

is a finite partition of  one has:

one has:

and here I would want to use finite additivity to remove the sum and bound by

and here I would want to use finite additivity to remove the sum and bound by  but the square root seems to prevent me from doing so. What is the trick I’m missing ?

but the square root seems to prevent me from doing so. What is the trick I’m missing ?

but then if

28 June, 2018 at 6:39 am

Terence Tao

Hmm, I see now that to get the sharp inequality one needs to already possess the functional calculus, since with that calculus one can write as

as  for some piecewise constant multiplier

for some piecewise constant multiplier  bounded in magnitude by 1. So to avoid circularity one may have to revert back to the depolarisation argument that loses an absolute constant (something like 4), since one does not need the sharp inequality at this stage of the construction.

bounded in magnitude by 1. So to avoid circularity one may have to revert back to the depolarisation argument that loses an absolute constant (something like 4), since one does not need the sharp inequality at this stage of the construction.

16 April, 2015 at 3:26 am

Ramesh

Can you please give a reference for the spectral theorem (multiplication form) for unbounded normal operators

18 August, 2015 at 9:39 am

A wave equation approach to automorphic forms in analytic number theory | What's new

[…] as discussed in this previous post, the spectral theory of an essentially self-adjoint operator such as is basically equivalent to […]

3 May, 2017 at 5:37 am

Anonymous

Would you say something about what would people do if the unbounded linear operator is not densely defined on a Hilbert space? Can it be reduced to the densely defined case?

7 June, 2017 at 3:08 am

Maths student

Can’t you just take the closure of the domain of definition, where the Hermitian form will be the restriction, to obtain a new, smaller Hilbert space, and get a self-map via orthogonal projection?

4 June, 2017 at 11:05 am

Maths student

If the operator is linear and densely defined, but the domain of definition is not a linear space, the ex. 1 seems to require even boundedness of L, even though I didn’t find a counter-example yet.

[In the definition of “densely defined”, the domain of definition is understood to be a linear subspace, not just a set (otherwise it does not makes sense to require $latex $L$ to be linear. -T]

8 June, 2017 at 1:03 am

Maths student

Let be densely defined on a set

be densely defined on a set  ,

,  a complex Hilbert space, and let

a complex Hilbert space, and let  and

and  . We call

. We call  linear iff

linear iff  implies

implies  .

.

5 June, 2017 at 1:28 am

Maths student

Dear Prof. Tao,

please add a bar to the L in the equation defining the Sobolev norm in ex. 2, and formulate: “The Sobolev space is defined as the domain of definition of the closed operator \overline L with Sobolev norm…”; indeed, closure can only be taken in spaces where you already have a norm on the larger space, as far as I know (on the other hand, the completion can be performed without any larger space around the space which is to be completed).

[“closure” replaced with “completion” -T.]

2 July, 2017 at 3:46 am

Maths student

Dear Prof. Tao, in the proof of Prop. 3 (i) please replace by

by  .

.

14 July, 2017 at 8:05 am

Oskar

In exercise 16 and 17 what is being meant with $\ll$?

23 July, 2017 at 9:35 am

Math student

In ex. 14 i) I’m having difficulty finding the right harmonic function to which to apply Liouville’s theorem; of course, the function needs to be defined on a whole real vector space, so I thought that I’d insert the exponential function, but the derivatives don’t want to cancel, in particular since we have a complicated convolution expression in there, which doesn’t seem to be easily evaluated. At this point, after several hours of thought, I raise the white flag. To which harmonic function do I have to apply Liouville?

23 July, 2017 at 2:12 pm

Terence Tao

Oops, I meant to say the maximum principle instead of Liouville’s theorem; I’ve updated the hint accordingly.

23 July, 2017 at 11:37 pm

Maths student

At least, I discovered Nelson’s proof of Liouville’s theorem: Pick any two points, apply the average formula to very large neighbourhoods of these points, and observe that the neighbourhoods are equal up to “small” sets which don’t really perturb the outcome by boundedness.

16 October, 2019 at 4:24 am

Mizar

Speaking of Exercise 14 (i), actually I can’t see it directly using the maximum principle, but rather by (odd) reflection in the hyperplane , which gives a bounded harmonic function on

, which gives a bounded harmonic function on  , and concluding with Liouville.

, and concluding with Liouville.

[Fair enough; I’ve removed the hint. -T]