Last updated: Apr 19, 2024

Analysis, Volume I

Terence Tao

Hindustan Book Agency, January 2006. Fourth edition, 2022. (Also Springer, Fourth edition, 2002.)

Hardcover, 368 pages.ISBN 81-85931-62-3 (first edition), 978-981-19-7261-4 (Springer fourth edition)

This is basically an expanded and cleaned up version of my lecture notes for Math 131A. In the US, it is available through the American Mathematical Society. It is part of a two-volume series; here is my page for Volume II. It is currently in its fourth edition. It will also be translated into French as “Le cours d’analyse de Terence Tao”.

There are no solution guides for this text.

- Sample chapters (contents, natural numbers, set theory, integers and rationals, logic, decimal system, index)

Errata to older versions than the corrected third edition can be found here.

— Errata to the corrected third edition —

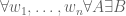

- Page 1: On the final line,

should be in math mode.

- Page 7: In Example 1.2.6, Theorem 19.5.1 should be “Theorem 7.5.1 of Analysis II”.

- Page 8: In Example 1.2.7, “Exercise 13.2.9” should be “Exercise 2.2.9 of Analysis II”. In Example 1.2.8, “Proposition 14.3.3” should be “Proposition 3.3.3 of Analysis II”. In Example 1.2.9, “Theorem 14.6.1” should be “Theorem 3.6.1 of Analysis II”.

- Page 9: In Example 1.2.10, “Theorem 14.7.1” should be “Theorem 3.7.1 of Analysis II”.

- Page 11: In the final line, the comma before “For instance” should be a period.

- Page 14: “without even aware” should be “without even being aware”.

- Page 17: In Definition 2.1.3, add “This convention is actually an oversimplification. To see how to properly merge the usual decimal notation for numbers with the natural numbers given by the Peano axioms, see Appendix B.”

- Page 19: After Proposition 2.1.8: “Axioms 2.1 and 2.2” should be “Axioms 2.3 and 2.4”.

- Page 20: In the proof of Proposition 2.1.11, the period should be inside the parentheses in both parentheticals. Also, Proposition 2.1.11 should more accurately be called Proposition Template 2.1.11.

- Page 23, first paragraph: delete a right parenthesis in

.

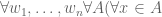

- Page 27: In the final sentence of Definition 2.2.7, the period should be inside the parentheses. In proposition 2.2.8, “

is positive” should be “

is a positive natural number”.

- Page 29: Add Exercise 2.2.7: “Let

be a natural number, and let

be a property pertaining to the natural numbers such that whenever

is true,

is true. Show that if

is true, then

is true for all

. This principle is sometimes referred to as the principle of induction starting from the base case

“.

- Page 31: “Euclidean algorithm” should be “Euclid’s division lemma”.

- Page 39: in the sentence before Proposition 3.1.18, the word Proposition should not be capitalised.

- Page 41: In the paragraph after Example 3.1.22, the final right parenthesis should be deleted.

- Page 45: at the end of the section, add “Formally, one can refer to

as “the set of natural numbers”, but we will often abbreviate this to “the natural numbers” for short. We will adopt similar abbreviations later in the text; for instance the set of integers

will often be abbreviated to “the integers”.”

- Page 47: In “In

did contain itself, then by definition”, add “of

“. After “On the other hand, if

did not contain itself,” add “then by definition of

“, and after “and hence”, add “by definition of

“.

- Page 48: In the third to last sentence of Exercise 3.2.3, the period should be inside the parenthesis.

- Page 49: “unique object

” should be “unique object

“, and similarly “exactly one

” should be “exactly one

“.

- Page 49+: change all occurrences of “range” to “codomain” (including in the index). Before Example 3.3.2, add the following paragraph: “Implicit in the above definition is the assumption that whenever one is given two sets

and a property

obeying the vertical line test, one can form a function object. Strictly speaking, this assumption of the existence of the function as a mathematical object should be stated as an explicit axiom; however we will not do so here, as it turns out to be redundant. (More precisely, in view of Exercise 3.5.10 below, it is always possible to encode a function

as an ordered triple

consisting of the domain, codomain, and graph of the function, which gives a way to build functions as objects using the operations provided by the preceding axioms.)”

- Page 51: Replace the first sentence of Definition 3.3.7 with “Two functions

,

are said to be equal if and only if they have the same domain and codomain (i.e.,

and

), and

for <I>all</I>

.” Then add afterwards: “According to this definition, two functions that have different domains or different codomains are, strictly speaking, distinct functions. However, when it is safe to do so without causing confusion, it is sometimes useful to “abuse notation” by identifying together functions of different domains or codomains if their values agree on their common domain of definition; this is analogous to the practice of “overloading” an operator in software engineering. See the discussion [in the errata] after Definition 9.4.1 for an instance of this.”

- Page 52: In Example 3.3.9, replace “an arbitrary set

” with “a given set

“. Similarly, in Exercise 3.3.3 on page 55, replace “the empty function” with “the empty function into a given set

“.

- Page 56: After Definition 3.4.1, replace “a challenge to the reader” with “an exercise to the reader”. In Definition 3.4.1, “

is a set in

” should be “latex S$ is a subset of

“.

- Page 62: Replace Remark 3.5.5 with “One can show that the Cartesian product

is indeed a set; see Exercise 3.5.1.”

- Page 65: Split Exercise 3.5.1 into three parts. Part (a) encompasses the first definition of an ordered pair; part (b) encompasses the “additional challenge” of the second definition. Then add a part (c): “Show that regardless of the definition of ordered pair, the Cartesian product

is a set. (Hint: first use the axiom of replacement to show that for any

, the set

is a set, then apply the axioms of replacement and union.)”. In Exercise 3.5.2, add the following comment: “(Technically, this construction of ordered

-tuple is not compatible with the construction of ordered pair in Exercise 3.5.1, but this does not cause a difficulty in practice; for instance, one can use the definition of an ordered

-tuple here to replace the construction in Exercise 3.5.1, or one can make a rather pedantic distinction between an ordered

-tuple and an ordered pair in one’s mathematical arguments.)”

- Page 66: In Exercise 3.5.3, replace “obey” with “are consistent with”, and at the end add “in the sense that if these axioms of equality are already assumed to hold for the individual components

of an ordered pair

, then they hold for an ordered pair itself”. Similarly replace “This obeys” with “This is consistent with” in Definition 3.5.1 on page 62.

- Page 67: In Exercise 3.5.12, add “Let

be an arbitrary set” after the first sentence, and let

be a function from

to

rather than from

to

; also

should be an element of

rather than a natural number. This generalisation will help for instance in establishing Exercise 3.5.13.

- Page 68: In the first paragraph, the period should be inside the parenthetical; similarly in Example 3.6.2.

- Page 71: The proof of Theorem 3.6.12 can be replaced by the following, after the first sentence: ” By Lemma 3.6.9,

would then have cardinality

. But

has equal cardinality with

(using

as the bijection), hence

, which gives the desired contradiction. Then in Exercise 3.6.3, add “use this exercise to give an alternate proof of Theorem 3.6.12 that does not use Lemma 3.6.9.”.

- Page 73: In Exercise 3.6.8, add the hypothesis that

is non-empty.

- Page 77: “negative times positive equals positive” should be “negative times positive equals negative”. Change “we call

a negative integer“, to “we call

a positive integer and

a negative integer“.

- Page 89: In the first paragraph, insert “Note that when

, the definition of

provided by Definition 4.3.11 coincides with the reciprocal of

defined previously, so there is no incompatibility of notation caused by this new definition.”

- Page 94, bottom: “see Exercise 12.4.8” should be “see Exercise 1.4.8 of Analysis II”.

- Page 97: In Example 5.1.10, “1-steady” should be “0.1-steady”, “0.1-steady” should be “0.01-steady”, and “0.01-steady” should be “0.001-steady”.

- Page 104: In the proof of Lemma 5.3.7, after the mention of 0-closeness, add “(where we extend the notion of

-closeness to include

in the obvious fashion)”, and after Proposition 4.3.7, add “(extended to cover the 0-close case)”.

- Page 113: In the second paragraph of the proof of Proposition 5.4.8, add “Suppose that

” after the first sentence.

- Page 122: Before Lemma 5.6.6: “

root” should be

roots”. In (e), add “Here

ranges over the positive integers”, and after “decreasing”, add “(i.e.,

whenever

)”. One can also replace

by

for clarity.

- Page 123, near top: “is the following cancellation law” should be “is another proof of the cancellation law from Proposition 4.3.12(c) and Proposition 5.6.3”.

- Page 124: In Lemma 5.6.9, add “(f)

.”

- Page 130: Before Corollary 6.1.17, “we see have” should be “we have”.

- Page 131: In Exercise 6.1.6,

should be

.

- Page 134: In the paragraph after Definition 6.2.6, add right parenthesis after “greatest lower bound of

“.

- Page 138: In the second paragraph of Section 6.4,

should be in math mode (three instances). After

in the proof of Proposition 6.3.10, add “(here we use Exercise 6.1.3.)”.

- Page 140: In the first paragraph,

should be in math mode.

- Page 143, penultimate paragraph: add right parenthesis after “

and

are finite”.

- Page 144: In Remark 6.4.16, “allows to compute” should be “allows one to compute”.

- Page 147: “(see Chapter 1)” should be “(see Chapter 1 of Analysis II)”.

- Page 148: In the first sentence of Section 6.6, replace

to

. After Definition 6.6.1, add “More generally, we say that

is a subsequence of

if there exists a strictly increasing function

such that

for all

.”.

- Page 153: Just before Proposition 6.7.3, “Section 6.7” should be “Section 5.6”.

- Page 157: At the end of Definition 7.1.6, add the sentence “In some cases we would like to define the sum

when

is defined on a larger set

than

. In such cases we use exactly the same definition as is given above.”

- Page 161: In Remark 7.1.12, change “the rule will fail” to “the rule may fail”.

- Page 163: In the proof of Corollary 7.1.14, the function

should be replaced with its inverse (thus

is defined by

. In Exercise 7.1.5, “Exercise 19.2.11” should be “Exercise 7.2.11 of Analysis II“.

- Page 166: In Remark 7.2.11 add “We caution however that in most other texts, the terminology “conditional convergence” is meant in this latter sense (that is, of a series that converges but does not converge absolutely).

- Page 172: In Corollary 7.3.7,

can be taken to be a real number instead of rational, provided we mention Proposition 6.7.3 next to each mention of Lemma 5.6.9.

- Page 175: A space should be inserted before the (why?) before the first display.

- Page 176: In Exercise 7.4.1, add “What happens if we assume

is merely one-to-one, rather than increasing?”. Add a new Exercise 7.4.2.: “Obtain an alternate proof of Proposition 7.4.3 using Proposition 7.4.1, Proposition 7.2.14, and expressing

as the difference of

and

. (This proof is due to Will Ballard.)”

- Page 177: In beginning of proof of Theorem 7.5.1, add “By Proposition 7.2.14(c), we may assume without loss of generality that

(in particulaar

is well-defined for any

).”.

- Page 178: In the proof of Lemma 7.5.2, after selecting

, add “without loss of generality we may assume that

“. (This is needed in order to take n^th roots later in the proof.) One can also replace

and

with

and

respectively.

- Page 186: In Exercise 8.1.4, Proposition 8.1.5 should be Corollary 8.1.6.

- Page 187, After Definition 8.2.1, the parenthetical “(and Proposition 3.6.4)” may be deleted.

- Page 188: In the final paragraph, after the invocation of Proposition 6.3.8, “convergent for each

” should be “convergent for each

“.

- Page 189, middle: in “Why? use induction”, “use” should be capitalised.

- Page 190: In the remark after Lemma 8.2.5, “countable set” should be “at most countable set”.

- Page 193: In Exercise 8.2.6, both summations

should instead be

.

- Page 198: In Example 8.4.2, replace “the same set” with “essentially the same set (in the sense that there is a canonical bijection between the two sets)”.

- Page 203: In Definition 8.5.8, “every non-empty subset of

has a minimal element

” should be “every non-empty subset

of

has a minimal element

“.

- Page 203: In Proposition 8.5.10, “Prove that

is true” should be “Then

is true”.

- Page 204: Before “Let us define a special class….”, add “Henceforth we fix a single such strict upper bound function

“.

- Page 205: The assertion that

is good requires more explanation. Replace “Thus this set is good, and must therefore be contained in

” with : “We now claim that

is good. By the preceding discussion, it suffices to show that

when

. If

this is clear since

in this case. If instead

, then

for some good

. Then the set

is equal to

(why? use the previous observation that every element of

is an upper bound for

for every good

), and the claim then follows since

is good. By definition of

, we conclude that the good set

is contained in

“. In the statement of Lemma 8.5.15, add “non-empty” before “totally ordered subset”.

- Page 206: Remove the parenthetical “(also called the principle of transfinite induction)” (as well as the index reference), and in Exercise 8.5.15 use “Zorn’s lemma” in place of “principle of transfinite induction”. In Exercise 8.5.6, “every element of

” should be “every element of

“.

- Page 208: In Exercise 8.5.18, “Tthus” should be “Thus”. In Exercise 8.5.16, “total orderings of

” should be “total orderings of

“.

- Page 211: In Definition 9.1.1, the endpoints of an interval should only be defined when the interval is non-empty; similarly, in Examples 9.1.3, it is only the non-empty intervals with one or more endpoints infinite that should be called half-infinite or infinite. In Remark 9.1.2, add that for a non-empty interval

, the left endpoint can also be equivalently defined as $\inf I$ (why?), and similarly the right endpoint can be equivalently defined as $\sup I$. In particular, this makes it clear that these notions of endpoint are well-defined (two non-empty intervals that are equal as sets, will have the same endpoints).

- Page 215: Exercise 9.1.1 should be moved to be after Exercise 9.1.6, as the most natural proof of the former exercise uses the latter.

- Page 216: In Exercise 9.1.8, add the hypothesis that

is non-empty. In Exercise 9.1.9, delete the hypothesis that

be a real number.

- Page 221: At the end of Remark 9.3.7,

should be

.

- Page 222: Replace the second sentence of proof of Proposition 9.3.14 by “Let

be an arbitrary sequence of elements in

that converges to

.”

- Page 223: Near bottom, in “Why? use induction”, “use” should be capitalised.

- Page 224: In Example 9.3.17, (why) should be (why?). In Example 9.3.16, “drop the set

” should be “drop the set

“, and change

to

.

- Page 225: In Example 9.3.20, all occurrences of

should be

.

- Page 226: After Definition 9.4.1, add “We also extend these notions to functions

that take values in a subset

of

, by identifying such functions (by abuse of notation) with the function

that agrees everywhere with

(so

for all

) but where the codomain has been enlarged from

to

.

- Page 230: In Exercise 9.4.1, “six equivalences” should be “six implications”. “Exercise 4.25.10” should be “Exercise 4.25.10 of Analysis II“.

- Page 231: In the second paragraph after Example 9.5.2, Proposition 9.4.7 should be 9.3.9. In Example 9.5.2, all occurrences of

should be

. In the sentence starting “Similarly, if

…”, all occurrences of

should be

.

- Page 232: In the proof of Proposition 9.5.3, in the parenthetical (Why? the reason…), “the” should be capitalised. Proposition 9.4.7 should be replaced by Definition 9.3.6 and Definition 9.3.3.

- Page 233-234: In Definition 9.6.1, replace “if” with “iff” in both occurrences.

- Page 235: In Definition 9.6.5, replace “Let …” with “Let

be a subset of

, and let …”.

- Page 237: Add Exercise 9.6.2: If

are bounded functions, show that

, and

are also bounded functions. If we furthermore assume that

for all

, is it true that

is bounded? Prove this or give a counterexample.”

- Page 248: Remark 9.9.17 is incorrect. The last sentence can be replaced with “Note in particular that Lemma 9.6.3 follows from combining Proposition 9.9.15 and Theorem 9.9.16.”

- Page 252: In the third display of Example 10.1.6, both occurrences of

should be

.

- Page 253: In the paragraph before Corollary 10.1.12, after “and the above definition”, add “, as well as the fact that a function is automatically continuous at every isolated point of its domain”.

- Page 256: In Exercise 10.1.1,

should be

, and “also limit point” should be “also a limit point”.

- Page 257: In Definition 10.2.1, replace “Let …” with “Let

be a subset of

, and let …”. In Example 10.2.3, delete the final use of “local”. In Remark 10.2.5,

should be

.

- Page 259: In Exercise 10.2.4, delete the reference to Corollary 10.1.12.

- Page 260: In Exercise 10.3.5,

should be

.

- Page 261: In Lemma 10.4.1 and Theorem 10.4.2, add the hypotheses that

, and that

are limit points of

respectively.

- Page 262. In the parenthetical ending in “$latex f^{-1} is a bijection”, a period should be added.

- Page 263: In Exercise 10.4.1(a), Proposition 9.8.3 can be replaced by Proposition 9.4.11.

- Page 264: In Proposition 10.5.2, the hypothesis that

be differentiable on

may be weakened to being continuous on

and differentiable on

, with

only assumed to be non-zero on

rather than

. In the second paragraph of the proof “converges to

” should be “converges to

“.

- Page 265: In Exercise 10.5.2, Exercise 1.2.12 should be Example 1.2.12.

- Page 266: “Riemann-Steiltjes” should be “Riemann-Stieltjes”.

- Page 267: In Definition 11.1.1, add “

is nonempty and” before “the following property is true”, and delete the mention of the empty set in Example 11.1.3. In Lemma 11.1.4, replace “connected” by “either connected or empty”. (The reason for these changes is to be consistent with the notion of connectedness used in Analysis II and in other standard texts. -T.)

- In the start of Appendix A.1, “relations between them (addition, equality, differentiation, etc.)” should be “operations between them (addition, multiplication, differentiation, etc.) and relations between them (equality, inequality, etc.)”.

- Page 276: In the proof of Lemma 11.3.3, the final inequality should involve

on the RHS rather than

.

- Page 280: In Remark 11.4.2, add “We also observe from Theorem 11.4.1(h) and Remark 11.3.8 that if

is Riemann integrable on a closed interval

, then

.

- Page 282: In Corollary 11.4.4, replace”

” by “

, defined by

“, and add at the end “(To prove the last part, observe that

.)”

- Page 283: In the penultimate display,

should be

.

- Page 284: Exercise 11.4.2 should be moved to Section 11.5, since it uses Corollary 11.5.2.

- Page 288: In Exercise 11.5.1, (h) should be (g).

- Page ???: At the start of the proof of Proposition 11.6.1, add “We may assume that

, since the claim is vacuously true otherwise.”.

- Page 291: In the paragraph before Definition 11.8.1, remove the sentences after “defined as follows”. In Definition 11.8.1, add the hypothesis that

be monotone increasing, and

be an interval that is closed in the sense of Definition 9.1.15, and alter the definition of

as follows. (i) If

is empty, set

. (ii) If

is a point, set

, with the convention that

(resp.

) is

when

is the right (resp. left) endpoint of

. (iii) If

, set

. (iv) If

,

, or

, set

equal to

,

, or

respectively. After the definition, note that in the special case when

is continuous, the definition of

for

simplifies to

, and in this case one can extend the definition to functions

that are continuous but not necessarily monotone increasing. In Example 11.8.2, restrict the domain of

to

, and delete the example of

.

- Page 292: In Example 11.8.6, restrict the domain of

to

. In Lemma 11.8.4 and Definition 11.8.5, add the condition that

be an interval that is closed, and

be monotone increasing or continuous.

- Page 293: After Example 11.8.7, delete the sentence “Up until now, our function… could have been arbitrary.”, and replace “defined on a domain” with “defined on an interval that is closed” (two occurrences).

- Page 294: The hint in Exercise 11.8.5 is no longer needed in view of other corrections and may be deleted.

- Page 295: In the proof of Theorem 11.9.1, after the penultimate display

, one can replace the rest of the proof of continuity of

with “This implies that

is uniformly continuous (in fact it is Lipschitz continuous, see Exercise 10.2.6), hence continuous.”

- Page 297: In Definition 11.9.3, replace “all

” with “all limit points

of

“. In the proof of Theorem 11.9.4, insert at the beginning “The claim is trivial when

, so assume

, so in particular all points of

are limit points.”. When invoking Lemma 11.8.4, add “(noting from Proposition 10.1.10 that

is continuous)”.

- Page 298: After the assertion

, add “Note that

, being differentiable, is continuous, so we may use the simplified formula for the

-length as opposed to the more complicated one in Definition 11.8.1.”

- Page 299: In Exercise 11.9.1,

should lie in

rather than

. In Exercise 11.9.3,

should lie in

rather than

. In the hint for Exercise 11.9.2, add “(or Proposition 10.3.3)” after “Corollary 10.2.9”.

- Page 300: In the proof of Theorem 11.10.2, Theorem 11.2.16(h) should be Theorem 11.4.1(h).

- Page 310: in the last line, “all logicallly equivalent” should be “all logically equivalent”.

- Page 311: In Exercise A.1.2, the period should be inside the parentheses.

- Page 327: In the proof of Proposition A.6.2,

may be improved to

; similarly for the first line of page 328. Also, the “mean value theorem” may be given a reference as Corollary 10.2.9.

- Page 329: At the end of Appendix A.7, add “We will use the notation

to indicate that a mathematical object

is being identified with a mathematical object

.”

- Page 334: In the last paragraph of the proof of Theorem B.1.4, “the number

has only one decimal representation” should be “the number

has only one decimal representation”.

— Errata to the fourth edition —

- General: all instances of “supercede” should be “supersede”, and “maneuvre” should be “manoeuvre”.

- Page xv: “Chapter 5 (on Fourier Series)” should be “Chapter 5 of Analysis II (on Fourier Series)”.

- Page 5: “theirbooks” should be “their books”.

- Page 10: In Example 1.2.12, final paragraph,

should be

.

- Page 15: “carry of digits” should be “carry digits”.

- Page 16: The semicolon before

should be a colon.

- Page 17: the computing language C should not be italicised.

- Page 20: In the parenthetical, “

“is not a half-integer”” should be “”

is not a half-integer””, i.e., the

should be inside the quotes.

- Page 22: In Remark 2.1.5, the first “For instance” may be deleted.

- Page 36: In Example 3.1.10: “lie on” should be “lie in”.

- Page 39: In the last part of Definiton 3.1.14, “if” should be “iff”.

- Page 40: In Remark 3.1.26, “elementsof” should be “elements of”.

- Page ???: In the parenthetical to Exercise 3.3.1, replace “are immediate from … in question, but the point” with “would be immediate from … in question, but as discussed in Remark 3.3.8, the axioms of equality for functions require justification. The point…”

- Page ???: In the statement of Lemma 3.4.10, replace “Then the set” with “Then”.

- Page 51: Delete the second part of Exercise 3.4.6 (it is redundant in view of Exercise 3.5.11), and replace “see also Exercise 3.5.11” with “see Exercise 3.5.11 for a converse to this exercise, which also helps explain why we refer to Axiom 3.11 as the “power set axiom”.”

- Page 60?: In Remark 3.4.13, “Ernest” should be “Ernst”.

- Page 66?: In Exercise 3.5.6, “the

” should be “the sets

“.

- Page 68?: In Exercise 3.5.2, the domain of

should be

rather than

.

- Page ??: In Exercise 3.5.12,

should be a function from

to

, and

should be

.

- Page 69: In the paragraph before Definition 3.6.5,

should be

.

- Page 70: In the fifth line of the proof of Lemma 3.6.9,

should be

.

- Page 77: In footnote 1, “two applications of the axiom of replacement” should be “the axiom of replacement”.

- Page 87: In Proposition 4.3.7(b), add the following parenthetical: “Because of this equivalence, we will also use “

and

are

-close” synonymously with either “

is

-close to

” or “

is

-close to

“.

- Page ???: Delete the last sentence of Exercise 4.4.3 (as the axiom of choice has not yet been formally introduced.)

- Page ???: In Remark 5.2.4 “Oepsilon-close” should be “epsilon-close”.

- Page 104?: In the sixth line from the bottom of the proof of Proposition 5.2.8, delete the first “yet”.

- Page 104: In the statement of Lemma 5.3.6, delete the space before the close parenthesis.

- Page 109: In the top paragraph (after Proposition 5.3.11), “On obvious guess” should be “One obvious guess”. In the proof of Lemma 5.3.15, after “

“, “for all

“, should be “for all

“

- Page 116: The paragraph after Remark 5.4.11 may be deleted, since it is essentially replicated near Definition 6.1.1.

- Page ???: In Remark 5.5.15 “the greatestlower bound” is missing a space.

- Page 148: After Definition 6.6.1, “for all

” should be “for all

“.

- Page 161: In the third display, on the right-hand side of the equation, the sizes of the first two left parentheses should be interchanged.

- Page ???: In the proof of Lemma 6.7.1, remove absolute values from second display for consistency.

- Pages 167-168: In Lemma 8.2.3 and Definition 8.2.4,

should be

.

- Page ???: In Lemma 7.1.4(a), the condition

may be relaxed to

.

- Page 174: In Proposition 7.4.1,

should be

, and similarly

should be

(two occurrences)

- Page ???: At the end of Example 7.4.2, “Exercise 5.5.2” should be “Exercise 5.5.2 of Analysis II”.

- Page ???: In Example 7.4.4, “see Example 4.5.7” should be “see Example 4.5.7 of Analysis II”.

- Page 177: In Exercise 7.3.2, add the requirement

to the geometric series formula.

- Page ???: In the proof of Theorem 8.2.2 just before the second display, “convergent for each

” should be “convergent for each

“.. In the second display, the first

sign can be replaced with equality. Two lines later, “Takingsumprema of this” is missing a space.

- Page 170: At the end of Section 8.2, add the following exercise (Exercise 8.2.7): “Let

be a function. Show that

is absolutely convergent if and only if

is convergent.”

- Page 198: In Example 8.4.2, replace “For any sets

and

” with “For any set

and non-empty set

“.

- Page 200: In Remark 8.3.5, “Exercise 7.2.6” should be “Exercise 7.2.6 of Analysis II“.

- Page 201: In the first paragraph of Section 8.4, “Section 7.3” should be “Section 7.3 of Analysis II“.

- Page 205: In Proposition 8.5.10, replace

with

.

- Page 207: In Exercise 8.5.15, replace the hint with “Apply Zorn’s lemma to the set of pairs

, where

is a subset of

and

is an injection, after giving this set a suitable partial ordering.”

- Page ???: In Exercise 8.5.20, “a subcollection

” is missing a space.

- Page ???: In Remark 9.1.25, “Section 1.5” should be “Section 1.5 of Analysis II”.

- Page 215: In the final paragraph of the proof of Lemma 9.1.12,

should be

.

- Page 219: In Remark 9.1.25, “Theorem 1.5.7” should be “Theorem 1.5.7 of Analysis II“.

- Page ???: In Remark 9.3.15, for completeness one can also include “

”.

- Page 231: In Example 9.4.3, in the second limit,

should be

.

- Page ???: In the paragraph after Proposition 9.4.11, “see Exercise 4.5.10” should be “see Exercise 4.5.10 of Analysis II”.

- Page 234: To improve the logical ordering, Proposition 9.4.13 (and the preceding paragraph) can be moved to before Proposition 9.4.10 (and similarly Exercise 9.4.5 should be moved to before Exercise 9.4.3, 9.4.4).

- Page 237: At the start of Section 9.7, “a continuous function attains” should be “a continuous function on a closed interval attains”.

- Page 241: In the proof of Proposition 9.6.7, “in Proposition 2.3.2” should be “… Proposition 2.3.2 of Analysis II”.

- Page ???: In the second paragraph of Section 9.9, the “island of stability” can be defined as a closed interval rather than an open one for consistency with the rest of the text.

- Page 249: In the first display of the proof of Theorem 9.9.16,

should be

.

- Page ???: In the first paragraph of Section 9.10, “see Section 2.5” should be “see Section 2.5 of Analysis II”.

- Page ???: In Example 9.10.4, (0, infty) should be (0, +infty) (two occurrences).

- Page ???: In Exercise 10.4.1, change the codomain to

for consistency. Also, replace

with

throughout this set of exercises.

- Page 252: In Definition 11.8.1, “a interval” should be “an interval”. In (ii), “

is the right endpoint” should be “

is the right endpoint”, and the final right parenthesis should be deleted. In (iii),

should be

, and the colons in the limits should be semicolons. In (iv), all occurrences of

should be

for notational consistency. Add an exercise to the effect that the limits in (ii), (iii) are well-defined, and refer to this exercise in the definition.

- Page 253: In Lemma 11.8.4, the word “which” may be omitted, as can the “continuous” case (for consistency).

- Page 255: In Theorem 10.1.13(h), enlarge the parentheses around

.

- Page 271: In Remark 11.1.2, “Section 2.4” should be “Section 2.4 of Analysis II“.

- Page ???: In the proof of Theorem 11.1.13,

can be

for consistency.

- Page ???: In Exercise 11.1.3,

should be

(two occurrences), and “

is not of the form” should be “none of the

are of the form”.

- Page 278: In Remark 11.3.5, replace “this is the purpose of the next section” with “see Proposition 11.3.12”. (Also one can mention that this definition of the Riemann integral is also known as the Darboux integral.)

- Page 281: In Remark 11.3.8, “Chapter 8” should be “Chapter 8 of Analysis II“.

- Page ???: In the proof of Theorem 11.5.1, the strict inequalities involving epsilon and delta can be replaced with non-strict inequalities for consistency with the rest of the book.

- Page ???: In Exercise 11.6.5, note that an alternate proof can also be obtained by adapting the proof of Corollary 7.3.7.

- Page 292: In Remark 11.7.2, “Chapter 8” should be “Chapter 8 of Analysis II“.

- Page ???: At the end of Section 11.8, the reference to the breakdown of Theorem 11.4.1(g) should be deleted.

- Page 294:

should be

(two occurrences).

- Page 297: In Definition 11.9.3, “all limit points

of

” should be “all limit points

of

that are contained in

“.

- Page 314: In Examples A.2.1, “no conclusion on

or

” should be “no conclusion for

“.

- Page 331: In the proof of Proposition A.6.2, 0 \leq y \leq x may be improved to 0 < y < x; similarly for the first line of page 332.

- Page ???: In the paragraph immediately after proof of Theorem B.1.4, “Onceone has this” is missing a space.

- Page ???: In Definition B.2.1, note that the + sign is often omitted from the decimal representation.

- Page ???: In the proof of Theorem B.2.2, many of the indices of

need to have their sign flipped for consistency, e.g.,

should be

.

- Page ???: In Exercise B.2.3, “

is not at terminating decimal” should be “

is not a terminating decimal”.

- In the index, the entries for ++ and for Cauchy-Schwarz are duplicated in some issues.

- General LaTeX issues: Use \text instead of \hbox for subscripted text. Some numbers (such as 0) are not properly placed in math mode in certain places. Some instances of \ldots should be \dots. \lim \sup should be \limsup, and similarly for \lim \inf.

Thanks to aaron1110, Adam, James Ameril, Paulo Argolo, William Barnett, José Antonio Lara Benítez, Dingjun Bian, Philip Blagoveschensky, Tai-Danae Bradley, Brian, Eduardo Buscicchio, Maurav Chandan, Diego Cimadom, Matheus Silva Costa, Gonzales Castillo Cristhian, Ck, William Deng, Kevin Doran, Lorenzo Dragani, Jonas Esser, Evangelos Georgiadis, Elie Goudout, Ti Gong, Cyao Gramm, Christian Gz., Ulrich Groh, Yaver Gulusoy, Deniz İmge, Minyoung Jeong, Erik Koelink, Brett Lane, David Latorre, Kyuil Lee, Matthis Lehmkühler, Bin Li, Percy Li, Matthew, Ming Li, Mufei Li, Yingyuan Li, Manoranjan Majji, Mercedes Mata, Simon Mayer, Pieter Naaijkens, Vineet Nair, Cristina Pereyra, Olli Pottonen, Huaying Qiu, David Radnell, Tim Reijnders, Issa Rice, Eric Rodriguez, Pieter Roffelsen, Luke Rogers, Feras Saad, Gabriel Salmerón, Vijay Sarthak, Leopold Schlicht, Marc Schoolderman, Rainer aus dem Spring, SkysubO, sotpau, Tim Smith, Sundar, suinwethilo, Karim Taha, Chaitanya Tappu, Winston Tsai, Kent Van Vels, Andrew Verras, Daan Wanrooy, John Waters, Yandong Xiao, Hongjiang Ye, Luqing Ye, Christopher Yeh, Muhammad Atif Zaheer, and the students of Math 401/501 and Math 402/502 at the University of New Mexico for corrections.

1,248 comments

Comments feed for this article

30 June, 2023 at 3:24 am

yyn

Dear Professor Tao

I am studying the axiom of replacement and find that there are several versions in different books.

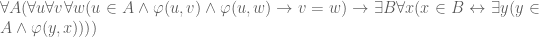

1.

2.

The first version is the same as in your book. The second one appears in some book about set theory. So are the two versions of the axiom of replacement equivalent?

6 August, 2023 at 6:02 am

Yingyuan Li

I have also thought about this question and I think they are equivalent because it can be proved that the two versions can be implied by each other, although the “class” might be different in the two version. In the first version, only the “restriction” of the class to

might be different in the two version. In the first version, only the “restriction” of the class to  is a function. But in the second version, the class itself is already a function.

is a function. But in the second version, the class itself is already a function.

Hope it could be verified!

14 July, 2023 at 5:13 am

Jonas Esser

Minor nitpick: I think the proof of Proposition 11.6.1 is missing the usual disclaimer along the lines of “the result is trivial if [a,b] is empty, so we will assume that a \leq b]."

Without this assumption, {b} is not necessarily a subset of [a,b], and so the partition described in the proof may not actually be a partition of [a,b].

[Erratum added, thanks – T.]

21 July, 2023 at 5:49 pm

Alex

Dear Professor Tao,

I am currently studying your book, Analysis I (4th Edition), and I would first like to express my gratitude for such an excellent resource. It emulates the richness of a live lecture, providing clarity to complex concepts.

While studying, I encountered Lemma 5.3.17 (on page 94) and a doubt arose. In the context of asserting that the reciprocal is well-defined, isn’t it necessary to demonstrate that the operation fulfills the axiom of substitution for all real numbers, excluding zero, not just for those distinctly bounded away from zero?

In essence, can the reciprocal, as defined, satisfy the axiom of substitution for all real numbers?

Thank you in advance for your time and any clarification you can provide.

29 July, 2023 at 10:55 am

Terence Tao

Because of Lemma 5.3.14, every non-zero real number is the (formal) limit of a Cauchy sequence bounded away from zero. (It is the sequence that is bounded away from zero, not the real number itself.)

22 July, 2023 at 2:12 am

Diego Cimadom

Dear Professor Tao,

I am reading the third edition of Analysis I and I believe to have found a typo. Page 67, exercise 3.5.12. In the hint the book says: “…such that and

and  for all

for all  . However, I believe it should say

. However, I believe it should say  instead as the function

instead as the function  has not been defined yet and we only have

has not been defined yet and we only have  .

.

Please forgive me if I misunderstood the exercise and there is no typo. I thought it was worth checking.

[Correction added, thanks – T.]

24 July, 2023 at 3:59 pm

sotpau

Very minor typo; in the fourth edition of Analysis I at page 40, Remark 3.1.25, the last of word of the page is “elementsof” in one word.

I usually talk myself out of sharing typos here at the risk of having missed something so I’m sorry if that is the case here too. The weird thing is that it is fixed for the digital version.

[Correction added, thanks – T.]

25 July, 2023 at 4:48 am

Deniz İmge

Greetings,

In exercise 3.5.12, shouldn’t the domain of the function a be N instead of X? Because the following function values are defined on domain values in N, like a(0) and a(n++).

2 August, 2023 at 7:54 am

adamfennell27

Dear Professor Tao,

I have a few questions regarding Analysis I (Fourth Edition).

1. On page 24, it asks why the sum of two natural numbers is again a natural number, using Axioms 2.1, 2.2, and 2.5. My proof is as follows, but doesn’t use Axiom 2.1? Have I made a mistake in my proof? [Fair enough, Axiom 2.1 is only implicitly used, as Axiom 2.5 does not really make sense without Axiom 2.1. -T.]

Let be natural numbers. We want to show that

be natural numbers. We want to show that  is also a natural number. We do this via induction. Let

is also a natural number. We do this via induction. Let  be the statement

be the statement  is a natural number. We see that

is a natural number. We see that  is a natural number, so $latex $\boldsymbol{P}(0)$ is true. Now suppose that

is a natural number, so $latex $\boldsymbol{P}(0)$ is true. Now suppose that  is true, so

is true, so  is a natural number. Then,

is a natural number. Then,  is also a natural number as

is also a natural number as  is a natural number and by using Axiom 2.2. Hence,

is a natural number and by using Axiom 2.2. Hence,  is also true. Thus

is also true. Thus  is true for every natural number

is true for every natural number  , by Axiom 2.5.

, by Axiom 2.5.

2. On page 50, it asks why do functions obey the axiom of substitution? I.e. . Is my proof below correct, by assuming that well-defined properties (that define functions) obey the axiom of substitution? [Yes. -T.]

. Is my proof below correct, by assuming that well-defined properties (that define functions) obey the axiom of substitution? [Yes. -T.]

Define by some property

by some property  , and suppose that

, and suppose that  . We want to show that

. We want to show that  . By definition

. By definition  is such that

is such that  is true. Thus, we have that

is true. Thus, we have that  is true since

is true since  (by the axiom of substitution for a well-defined property). But by definition, this means that

(by the axiom of substitution for a well-defined property). But by definition, this means that  , as required.

, as required.

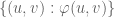

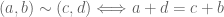

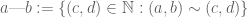

3. On page 77, it discusses how in the language of set theory, to construct the integers, we consider the space , place an equivalence relation by declaring

, place an equivalence relation by declaring  , and define

, and define  . Then it says the existence of the set

. Then it says the existence of the set  requires two applications of the axiom of replacement. Why isn’t it just one application, since we can have the statement

requires two applications of the axiom of replacement. Why isn’t it just one application, since we can have the statement  as

as  , where

, where  are the first and second components of the ordered pair

are the first and second components of the ordered pair  ? In other words, we just directly replace every element

? In other words, we just directly replace every element  by

by  .

.

[Fair enough, I have added an erratum to this remark. -T]

Any help would be greatly appreciated.

21 August, 2023 at 11:42 pm

77077

Dear Professor Tao,

4.1,-(a—b):=(0—1)·(a—b),Is this OK?

22 August, 2023 at 2:53 am

Anonymous

I mean which is better?

4.1.4 -(a—b):=(b—a)

Thanks

24 August, 2023 at 9:39 pm

Anonymous

Dear Professor Tao,

The last part of the proof for lemma 8.5.14 is written as follows:

“Thus we have constructed a set with no strict upper bound, as desired.”

However, at the beginning of the proof, starting with the assumption for sake of contradiction, it was shown that the statement “every well-ordered set with x_0 as a minimal element has a strict upper bound” is false.

So, can we claim that we have indeed constructed a set without a strict upper bound?

25 August, 2023 at 6:54 am

Terence Tao

It depends on what you mean by “construct”. If a statement of the form “every X obeys Y” is shown to lead to a contradiction, then there must exist an X which does not obey Y. (If, for instance, it is not possible for all participants in the stock market to simultaneously make a profit, then at any given point in time, there must be at least one participant in the stock market who is not making a profit). However, the argument is *nonconstructive*: it implies the existence of an X not obeying Y, but does not produce an algorithm for actually finding it. (For example, the above stock market argument does not tell us *who* is not profiting in the market at any given time.) Non-constructive arguments are permitted in the orthodox foundations of mathematics (which are largely based on first-order logic), but logicians have considered more restrictive foundations of mathematics (such as constructivist foundations) in which such a nonconstructive argument would not be considered valid.

25 August, 2023 at 7:48 pm

Anonymous

Thank you for your response, Professor.

I have one more question. Before the rigorous proof begins, there is the following content:

“Instead, what we will do is that we will isolate a collection of ‘partially completed’ sets Y, which we shall call good sets, and then take the union of all these good sets to obtain a ‘completed’ object Y_00 which will indeed have no strict upper bound.”

In this context, it is stated that Y_00 does not have a strict upper bound. However, in the final part of the proof, Y_00 ends up having a strict upper bound.

Why is there this difference between the two?

26 August, 2023 at 9:07 am

Terence Tao

This is how proof by contradiction works: one assumes that the claim one wants to show is *false*, and shows that this is absurd. If you like, the bulk of the proof is devoted to showing what *cannot* happen, rather than what *does* happen.

29 August, 2023 at 5:29 am

Anonymous

Thank you very much for your response, Professor. Thanks to you, I now understand how proof by contradiction works. However, there’s still a part that I don’t quite grasp.

We assumed that the claim we want to show is false: ‘every well-ordered subset Y of X which has x_0 as its minimal element, has strict upper bound.’ Based on this assumption, we used the axiom of choice to define a good set, and Y_oo is the union of these good sets. Y_oo has a strict upper bound, leading to a contradiction.

Therefore, we were able to establish the truth of the claim we wanted to prove: ‘there is a well-ordered subset Y of X which has x_0 as its minimal element, and which has no strict upper bound.’

However, is it also possible to conclude that Y_oo does not have a strict upper bound? Since Y_oo is defined under the assumption that the claim we want to prove is false, I felt that there might be an issue with this reasoning.

3 September, 2023 at 1:03 pm

Terence Tao

Well, from a hypothesis that leads to a contradiction, any conclusion can be validly drawn (this is the principle of explosion, also known as ex falso quodlibet).

1 September, 2023 at 4:38 am

Anonymous

Dear Professor Tao

If I don’t define the multiplication of 0, can I define it divided by 0?

22 September, 2023 at 2:49 am

Anonymous

In Exercise 3.3.1., we have the following addendum regarding equality of functions: “Of course, these statements are immediate from

the axioms of equality in Appendix A.7 applied directly to the functions…”. However, how can we be sure doing so won’t contradict the equality defined on the domain or codomain? Or even worse, how can we be sure it is consistent with the previous defined axioms of Set Theory? If we wish to keep the equality of functions as a definition and ensure it has the usual properties of equality, I guess the only option is to show it follows from the equality relation defined on the domain and codomain.

2 November, 2023 at 1:45 am

Anonymous

Dear Professor Tao,

It is mentioned in page 255 (4th ed) that Theorem 11.4.1(g) fails for Riemann–Stieltjes integrals, but I believe I have proven that this theorem holds.

I think that my claimed proof is incorrect due to that remark. Is there any counterexample to that theorem?

6 November, 2023 at 12:50 pm

Terence Tao

Good point; this remark pertained to a more problematic definition of the Riemann-Stieltjes integral that was in an earlier edition of the textbook, and should now be deleted.

26 November, 2023 at 9:34 am

Anonymous

In example 3.3.4 chapter-3 of Analysis 1, it was mentioned that function follow the axiom of substitution i.e. f(x) =f(y) for x=y.I want to know if this counter example contradicts this fact, f:Q→Z f(a/b)=a . By equality of rationals a/b=2a/2b . f(a/b)=a, f(2a/2b)=2a from above 2a=a but that is only true for a=0 which implies that all integers a=0 which is not true.

27 November, 2023 at 3:32 am

Adam Fennell

This is the reason that this example is NOT a (well-defined) function. We require functions to obey the axiom of substitution by definition. In particular, it is the statement/property that defines the function that must obey the axiom of substitution, which the function then inherits. So, in your example, the relevant property would be something like P(x,y) = “y is the numerator of x”, and f defined by y=f(x) if and only if P(x,y) is true. However, as you have pointed out, this does not obey the axiom of substitution, and hence isn’t actually a well-defined statement! Hope this helps.

27 November, 2023 at 6:39 am

Anonymous

Thanks

27 November, 2023 at 1:42 am

seeker

Hi Dr Tao,

Could you check if my below proof is correct? I struggled with this exercise a lot(never thought to use the previous part of the proposition) and think that I now have a proof.

Exercise: If is a limit point of a sequence, then we have that

is a limit point of a sequence, then we have that  .

.

Proof: We will prove only for . Suppose for the sake of contradiction that

. Suppose for the sake of contradiction that  . By a previous result, there exists an

. By a previous result, there exists an  such that for all

such that for all  , we have that

, we have that  and

and  , there exists an

, there exists an  such that

such that  . Which implies that

. Which implies that  we have that

we have that  , we have that

, we have that  . Which is a contradiction. Thus,

. Which is a contradiction. Thus,  .

.

30 November, 2023 at 10:51 pm

Anonymous

gonna see your writeup on ax. of replacement soon

T

1 December, 2023 at 11:12 pm

Anonymous

go to wikipedia, look for Axiom schema of specification:

axiom of replacement:

do not appear anywhere in your books.

T

2 December, 2023 at 9:14 am

Yingyuan Li

Dear Professor Tao,

Here is a possible minor errata.

In page 167-168, (Analysis I, Springer 4th edition), in Lemma 8.2.3 and Definition 8.2.4, the two occurrences of should be

should be  for consistency, since it is an extended real and in the previous chapter we have only introduced

for consistency, since it is an extended real and in the previous chapter we have only introduced  and

and  but not

but not  as elements of the extended real number system.

as elements of the extended real number system.

Best regards,

Yingyuan Li

[Errata added, thanks – T.]

3 December, 2023 at 7:48 am

Anonymous

Dear Professor Tao, in the proof of theorem 5.5.9 (Existence of least upper bound) you mentioned that the number Mn( such that L<Mn<K (K/n is an upper bound for set E subset of R whereas L/n is not) and Mn/n is an upper bound for E and Mn-1/n is not an upper bound ) exists but is unique. I want to know whether the fact that Mn is unique is essential for the proof of theorem 5.5.9 or not. My question could also be stated as ' If Mn wasn't unique without affecting any other mathematical fact would theorem 5.5.9 be false ?'.

3 December, 2023 at 8:18 am

Terence Tao

The uniqueness is not essential to the argument (although if it was not unique, one would have to appeal to either the axiom of choice, or some sort of well ordering property, in order to extract a well defined sequence ).

).

4 December, 2023 at 2:41 am

Anonymous

I think there is a problem with the end note of Exercise 3.3.1: it says we can apply the axioms of equality directly to the functions, but it doesn’t explain how this is consistent with Definition 3.3.8. Stating we can apply it to functions itself defeats the purpose of Remark 3.3.12, which says Definition 3.3.8 is not compatible with the axioms of equality at first sight.

[A rewording has been put in the errata, thanks – T.]

12 December, 2023 at 9:20 am

Anonymous

Dear Professor Tao in proposition 6.3.8 (monotone bounded sequences converge) it has been mentioned that every bounded sequence which is monotone converges. I want to know whether every sequence which is eventually monotone,ie;monotone for every n≥M for some M≥m (m is index of the sequence), converges or doesn’t for some sequences.

16 December, 2023 at 8:18 am

Terence Tao

Yes; convergence is about the asymptotic behavior of a sequence, and only the properties of the sequence which are eventually true are important. It would be a good exercise for you to see if you can modify the proof of that proposition to get that claim.

6 January, 2024 at 3:56 pm

Anonymous

Dear Professor Tao, for the proof of Theorem 8.2.2, to prove, sum_{0..N} [sum_{0..infinity} f(n, m)] <= L, you mention that we can use the limit laws and induction on N.

Isn't it enough to argue that, since every element of the sequence a_{M} is <= L, then the limit of the sequence will also be <= L.

Could you please also explain how one would use induction on N here?

Thank you so much!

21 January, 2024 at 7:31 pm

Terence Tao

You are implicitly using the fact that converges to

converges to  as

as  in your argument, but to actually deduce this fact from the fact that

in your argument, but to actually deduce this fact from the fact that  converges to

converges to  , you need the limit laws and an induction on

, you need the limit laws and an induction on  .

.

7 January, 2024 at 6:23 pm

Anonymous

Exercise 11.1.3

Prove that one of the intervals in this partition is of the form

in this partition is of the form  or

or  for some

for some  .

.

This claim is true but of no use in the proof of Theorem 11.1.13. For if contains an empty interval then we can set

contains an empty interval then we can set  making

making  empty. The claim is always true for any

empty. The claim is always true for any  containing an empty interval.

containing an empty interval.

What is supposed to be useful is:

Prove that one of the intervals in this partition is of the form

in this partition is of the form  or

or  for some

for some  .

.

The hint in that exercise also contains some error.

First show that if is not of the form

is not of the form  or

or  for any

for any

Better way of writing:

First show that if none of is of the form

is of the form  or

or  for any

for any

Note that is from the earlier correction.

is from the earlier correction.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

8 January, 2024 at 2:35 am

Anonymous

Surprisingly, the index of the Hindustan Book Agency Analysis I, fourth edition, contains entries that belong to the sequel Analysis II (This seems not to be the case with the Springer edition).

On the top of this blog page, the publication year of the Springer fourth edition should be 2022 instead of 20*0*2.

Thanks for this stimulating series as well as this errata list. PJ

10 January, 2024 at 7:53 pm

Anonymous

Dear Terence Tao,

I think that I am capable to translate your Analysis I to Spanish. I am used to write Mathematics and I have also a bit experience tranlating texts I remember that long time ago my Bachelord teacher gime a 10/10 in traduction haha. Anyway if you are interested send me a mail. Maybe I am not as good as you as Mathematician but maybe I could be your Émile du Châtelet, if you are not Newton I think that you are close to his geniality.

Juan Elías Millas Vera.

11 January, 2024 at 7:53 am

pkrananpc

Dear Professor Tao in definition 8.2.1 you defined series on countable sets.I want to know whether this definition is consistent with series which are not absolutely convergent

17 January, 2024 at 12:48 am

Anonymous

Dear Professor Tao,

In exercise 5.3.12 (i), I think function ‘a: X –> X’ should be ‘a: N –> X’. Hope to receive the answer from you

[Corrected (for Exercise 3.5.12), thanks – T.]

25 January, 2024 at 5:17 pm

Anonymous

The correction noted in the 3rd edition was not applied to the 4th edition, so unless there was a reason it wasn’t corrected, re-add this to the errata I suppose with these updated page numbers.

Page 331: In the proof of Proposition A.6.2, 0 \leq y \leq x may be improved to 0 < y < x; similarly for the first line of page 332.

[Added, thanks – T.]

25 January, 2024 at 5:37 pm

g.m. lime

Else there is interesting statements such as: 0 < y < x and 0 < x < epsilon, we see that 0<= y < epsilon.

5 February, 2024 at 11:47 pm

Anonymous

Dear Professor Tao

Does this make a function? In other words, is it correctly defined?

a function? In other words, is it correctly defined?

I had doubts while studying the recursive definition and the Axiom of Choice.

Let be a set with two elements. Through a single choice, we have an object

be a set with two elements. Through a single choice, we have an object  as an element of

as an element of  .

.

Now, let’s define the function as follows:

as follows:

![[ f : \{1\} \rightarrow X , f(1) = x ]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B+f+%3A+%5C%7B1%5C%7D+%5Crightarrow+X+%2C+f%281%29+%3D+x+%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002)

[Yes, this is a well-defined function. -T]

8 February, 2024 at 2:16 am

T Retsu

Note that piecewise-constant definition must disallow one-point interval. Well, a pseudo-partition must consist of non-trivial intervals whose lengths sum up to that of the interval .

.

For any , there are only finitely many intervals in the pseudo-partition whose lengths are

, there are only finitely many intervals in the pseudo-partition whose lengths are  .

.

This is quite a big challenge to rewrite Chapter 11.

13 February, 2024 at 9:10 pm

econsphdtutor

In the 4th edition, p. 270, you use the symbol “$\leftrightarrow$”. But in the rest of the book, you usually use the symbol “$\iff$” (e.g. pp. 29, 30, 33, 35, 38, 40, 48, 49, 50, 52, 53). Might it be that on p. 270, you also meant to use “$\iff$”? Or are these two symbols meant to be different?

[I cannot locate this symbol. Can you give more context as to its location, such as nearby equation numbers or proposition numbers? -T]

1 March, 2024 at 6:50 am

Adam Fennell

Dear Professor Tao,

When defining finite series (Definition 7.1.1), I just wanted to clarify that the and

and  used in the recursive definition are completely separate from the

used in the recursive definition are completely separate from the  and

and  used in assuming some finite sequence

used in assuming some finite sequence  . If I am correct in thinking this, how do we ensure that in the recursive definition we don’t accidently talk about some

. If I am correct in thinking this, how do we ensure that in the recursive definition we don’t accidently talk about some  which isn’t actually defined (i.e.,

which isn’t actually defined (i.e.,  is outside of the interval $\latex m \leq i \leq n$)?

is outside of the interval $\latex m \leq i \leq n$)?

It seems the easiest way would be to extend the finite sequence to an infinite one, where all other terms are 0. Although this would require in some sense going infinitely in both directions since we may wish to start the summation at any point; I suppose we could then just consider it to be a function , rather than from the natural numbers.

, rather than from the natural numbers.

Furthermore, how do we know this recursive definition is well-defined/exists? I know we have proved in general that we can define things recursively in Exercise 3.5.12, but this was when only inducting on one variable. It appears in this case we are inducting on two ( and

and  ) in some sense? Do we justify it by simply considering the starting limit of the sum to be fixed, and then define inductively on the upper limit? Although how does this work if

) in some sense? Do we justify it by simply considering the starting limit of the sum to be fixed, and then define inductively on the upper limit? Although how does this work if  is less than

is less than  ? I’m thinking it is only the recursive definition in the case

? I’m thinking it is only the recursive definition in the case  , and so we just have base case

, and so we just have base case  , and the case

, and the case  is a separate, non-recursive definition.

is a separate, non-recursive definition.

Naturally, this is all slightly pedantic, but I just want to make sure I am not misunderstanding something!

Any help is appreciated.

Many thanks,

Adam Fennell

(Note, this refers to the fourth edition of Analysis I)

17 March, 2024 at 5:48 pm

Terence Tao

It’s the same variables and

and  . If you like, we are recursively defining, for each pair

. If you like, we are recursively defining, for each pair  with

with  , a function from the collection of finite sequences

, a function from the collection of finite sequences  to the real numbers. Note that a sequence defined on

to the real numbers. Note that a sequence defined on  will also be defined on

will also be defined on  , so at no point would we need to evaluate a finite sequence at an index outside of its domain of definition.

, so at no point would we need to evaluate a finite sequence at an index outside of its domain of definition.

In the recursive definition, is never altered, only

is never altered, only  is, so the usual recursive process from Exercise 3.5.12 applies. It starts at

is, so the usual recursive process from Exercise 3.5.12 applies. It starts at  rather than at

rather than at  , but this is not a difficulty (one could for instance substitute

, but this is not a difficulty (one could for instance substitute  and use recursion on

and use recursion on  instead, if one preferred).

instead, if one preferred).

2 March, 2024 at 9:23 pm

Anonymous

Dear Professor Tao

When utilizing a recursive definition, is it always possible to find a function such as f:N×N→N?

And when writing the proof rigorously, is it necessary to specify f:N×N→N?

Exercise 3.5.12. This exercise will establish a rigorous version of Proposition

2.1.16. Let f : N×N → N be a function, and let c be a natural number. Show

that there exists a function a : N → N such that

a(0) = c

and

a(n++) = f(n, a(n)) for all n ∈ N,

and furthermore that this function is unique.

17 March, 2024 at 5:54 pm

Terence Tao

As noted in the errata, some of the natural number sets in the exercise should be replaced with a more general set, as per https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recursion#The_recursion_theorem . In practice, describing the specific function f one would apply the recursion theorem to is somewhat tedious, and one often describes the recursion using slightly more informal language, for instance by describing the process an an algorithm.

9 March, 2024 at 11:44 pm

Olli Pottonen

Dear Professor Tao,

I have same errata for the fourth edition errata.

“Page 24: In the analysis of Case 1 of the proof of Theorem 1.5.8 …”

This belongs in Analysis II errata.

“Page 39: In the last part of Definiton 3.1.15, …”

I think this should read Definition 3.1.14

“Page ???: In the parenthetical to Example 3.3.1, …”

This should read Exercise 3.3.1.

“Page 102: In the sixth line from the bottom of the proof, …”

In my book this is on page 104. Perhaps it is on different pages in Springer and Hindustani Book Agency versions? I assume reference to Proposition 5.2.8 would clarify both cases.

“Page 201: In the first paragraph of Section 8.4 …”

The next bullet point in the list should be merged to this one.

“Page 255: In Theorem 10.1.13(h) …”

This should be split into two different entries, one about differentiation and another about integration.

“Page ???: In Exercise B.2.3, …”

0 does have two different decimal representations, +0.000… and -0.000…

Best regards

Olli Pottonen

[Corrections added, thanks – T.]

13 April, 2024 at 10:44 pm

Olli Pottonen

Also I have new corrections/suggestions/comments:

On page xv of the Preface, “Chapter 5 (on Fourier Series)” should be “Chapter 5 of Analysis II (on Fourier Series)”.

In Remark 5.2.4 “Oepsilon-close” should be “epsilon-close”.

In Remark 5.5.15 “the greatestlower bound” is missing a space.

In the proof of Lemma 6.7.1, it is a bit inconsistent that the second display has d(x^{q_n}, x^{q_m}) = x^{q_n} – x^{q_m} but the third one d(x^{q_n}, x^{q_m}) = |x^{q_n} – x^{q_m}|.

In Lemma 7.1.4 (a) “m le n < p” could as well be “m le n le p”.

At the end of Example 7.4.2 “Exercise 5.5.2” should be “Exercise 5.5.2 of Analysis II”.

Corollaries 7.3.7 and 11.6.5 are the same result with different proofs. However in one case we claim convergence and in the other absolute convergece. Both are of course correct, but it’s a bit inconsistent.

In Example 7.4.4, “see Example 4.5.7” should be “see Example 4.5.7 of Analysis II”

In the proof of Theorem 8.2.2 just before the second display “sum_{m=0}^{infty} f(n, m) is convergent for each m” should be “… for each n”. In the second display first of two “le” should be “=”. And two lines down in the same proof “Takingsumprema of this” is missing a space.

In Exercise 8.5.20, “a subcollectionOmega’ subset Omega” is missing a space. int_{[P]} f” is missing a space.

In Remark 9.1.25, “Section 1.5” should be “Section 1.5 of Analysis II”.

Remark 9.3.15, for completeness we should also include “lim_{x rightarrow x_0} c f(x) = c lim_{x rightarrow x_0} f(x)”.

In the paragraph after Proposition 9.4.11, “see Exercise 4.5.10” should be “see Exercise 4.5.10 of Analysis II”.

In the proof of Proposition 9.6.7, p. 241, “in Proposition 2.3.2” should be “… Proposition 2.3.2 of Analysis II”.

In the second paragraph of Section 9.9 has “‘island of stability’ (x_0 – delta, x_0 + delta)”. Here [x_0 – delta, x_0 + delta] would be more consistent with the rest of the text.

In the first paragraph of Section 9.10, “see Section 2.5” should be “see Section 2.5 of Analysis II”.

In Example 9.10.4, (0, infty) should be (0, +infty) (two occurrences).

Exercices 10.4.1, 10.4.2, 10.4.3 are closely related and build on each other. Then it’s a bit inconsistent that function in the first one has codomain (0, infty) but in the other two the codomain is mathbb{R}. Also I think we should use +infty instead of just infty.

In the proof of theorem 11.1.13, the notation “I – K” is inconsistent with rest of the text which uses “I setminus K”. Then again both are consistent with Definition 3.1.26.

The proof of Theorem 11.5.1 has “|f(x) – f(x)| < epsilon whenever x, y in I are such that |x – y| < delta”. While correct, “|f(x) – f(x)| le epsilon … |x – y| le delta” would be more consistent with rest of the book.

In Lemma 11.8.4 it feels a bit odd to include continuous but non-monotone alpha as rest of the section only considers increasing alpha. Of course the lemma is perfectly correct.

In the paragraph immediately after proof of Theorem B.1.4, “Onceone has this” is missing a space.

In Definition B.2.1, “A real decimal is any sequence of digits, and a decimal point, …” add “signed”.

In Theorem B.2.2 the theorem statement and proof are inconsistent: in the statement the digits after decimal point are a_{-1}a_{-2}…, but in the proof they are a_{1}a_{2}…

In Proposition B.2.3, strictly speaking the representations should be +1.000… and +0.999…

In the Index, ++ (increment) and Cauchy-Schwarz appear twice, with slightly different punctuations.

[Added, thanks – T.]

16 March, 2024 at 4:06 am

Noel

Dear Professor Tao,

I am having trouble understanding Exercise 3.6.12 in Analysis I. We are asked to show that is finite, but then we are asked to prove a formula involving the cardinality of

is finite, but then we are asked to prove a formula involving the cardinality of  . So in what is presumably a proof by induction, we prove that

. So in what is presumably a proof by induction, we prove that  and

and  are finite in the same step. This doesn’t s

are finite in the same step. This doesn’t s

Regards,

Noel

16 March, 2024 at 4:12 am

Noel

Prove that is finite for all

is finite for all  and has the desired cardinality. Also prove that

and has the desired cardinality. Also prove that  is finite as a first step.

is finite as a first step.

28 March, 2024 at 9:58 pm

Anonymous

(In the 4th edition). In Remark 3.4.13, shouldn’t “Axioms 3.1 and 3.12” read “Axioms 3.1 to 3.12”? Also, in the same remark, “Ernest” should be “Ernst” (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_Zermelo).

[Latter correction added, though it seems the former one was already implemented (via a hyphen). -T]

28 March, 2024 at 10:48 pm

Anonymous

(In the 4th edition). For consistency, I would suggest using the same symbol for the empty set in Axiom 3.3. The first one is emptyset while the latter one is varnothing.

[I am not aware of any use of varnothing in the text. -T]

14 April, 2024 at 11:33 pm

Anonymous

I see the same inconsistency (despite Terry’s response). Axiom 3.3 uses two different symbols for the empty set. (Springer 4e)

[Very strange! as far as I can tell this is issue is not present in the source files. -T]

30 March, 2024 at 7:23 am

Anonymous

(In the 4th edition) In the proof of Lemma 3.15, it’s written that “We prove by contradiction.” But reading the proof, I feel that it should be written that we prove the contrapositive.

[Either is appropriate here. -T]

30 March, 2024 at 8:32 am

Anonymous

(In the 4th edition) In Example 3.1.10, “which either lie on” should be “which either lie in”.

[Correction added, thanks – T.]

1 April, 2024 at 12:10 pm

Anonymous

(In the 4th edition) In Definition 3.3.1 (Functions), the phrase “…defined by P on the domain X and codomain to…” should be “…defined by P on the domain X and codomain Y to…”.

[The variable is present (after the footnote). -T]

is present (after the footnote). -T]

7 April, 2024 at 1:46 am

Dale Matthews

I have the third edition and noticed Proposition 2.1.6 says 4 is “the increment of the increment of the increment of 0” but this would be 3 not 4.

[This appears to be addressed in the fourth edition already – T.]