Previous set of notes: Notes 0. Next set of notes: Notes 2.

At the core of almost any undergraduate real analysis course are the concepts of differentiation and integration, with these two basic operations being tied together by the fundamental theorem of calculus (and its higher dimensional generalisations, such as Stokes’ theorem). Similarly, the notion of the complex derivative and the complex line integral (that is to say, the contour integral) lie at the core of any introductory complex analysis course. Once again, they are tied to each other by the fundamental theorem of calculus; but in the complex case there is a further variant of the fundamental theorem, namely Cauchy’s theorem, which endows complex differentiable functions with many important and surprising properties that are often not shared by their real differentiable counterparts. We will give complex differentiable functions another name to emphasise this extra structure, by referring to such functions as holomorphic functions. (This term is also useful to distinguish these functions from the slightly less well-behaved meromorphic functions, which we will discuss in later notes.)

In this set of notes we will focus solely on the concept of complex differentiation, deferring the discussion of contour integration to the next set of notes. To begin with, the theory of complex differentiation will greatly resemble the theory of real differentiation; the definitions look almost identical, and well known laws of differential calculus such as the product rule, quotient rule, and chain rule carry over verbatim to the complex setting, and the theory of complex power series is similarly almost identical to the theory of real power series. However, when one compares the “one-dimensional” differentiation theory of the complex numbers with the “two-dimensional” differentiation theory of two real variables, we find that the dimensional discrepancy forces complex differentiable functions to obey a real-variable constraint, namely the Cauchy-Riemann equations. These equations make complex differentiable functions substantially more “rigid” than their real-variable counterparts; they imply for instance that the imaginary part of a complex differentiable function is essentially determined (up to constants) by the real part, and vice versa. Furthermore, even when considered separately, the real and imaginary components of complex differentiable functions are forced to obey the strong constraint of being harmonic. In later notes we will see these constraints manifest themselves in integral form, particularly through Cauchy’s theorem and the closely related Cauchy integral formula.

Despite all the constraints that holomorphic functions have to obey, a surprisingly large number of the functions of a complex variable that one actually encounters in applications turn out to be holomorphic. For instance, any polynomial with complex coefficients will be holomorphic, as will the complex exponential

. From this and the laws of differential calculus one can then generate many further holomorphic functions. Also, as we will show presently, complex power series will automatically be holomorphic inside their disk of convergence. On the other hand, there are certainly basic complex functions of interest that are not holomorphic, such as the complex conjugation function

, the absolute value function

, or the real and imaginary part functions

. We will also encounter functions that are only holomorphic at some portions of the complex plane, but not on others; for instance, rational functions will be holomorphic except at those few points where the denominator vanishes, and are prime examples of the meromorphic functions mentioned previously. Later on we will also consider functions such as branches of the logarithm or square root, which will be holomorphic outside of a branch cut corresponding to the choice of branch. It is a basic but important skill in complex analysis to be able to quickly recognise which functions are holomorphic and which ones are not, as many of useful theorems available to the former (such as Cauchy’s theorem) break down spectacularly for the latter. Indeed, in my experience, one of the most common “rookie errors” that beginning complex analysis students make is the error of attempting to apply a theorem about holomorphic functions to a function that is not at all holomorphic. This stands in contrast to the situation in real analysis, in which one can often obtain correct conclusions by formally applying the laws of differential or integral calculus to functions that might not actually be differentiable or integrable in a classical sense. (This latter phenomenon, by the way, can be largely explained using the theory of distributions, as covered for instance in this previous post, but this is beyond the scope of the current course.)

Remark 1 In this set of notes it will be convenient to impose some unnecessarily generous regularity hypotheses (e.g. continuous second differentiability) on the holomorphic functions one is studying in order to make the proofs simpler. In later notes, we will discover that these hypotheses are in fact redundant, due to the phenomenon of elliptic regularity that ensures that holomorphic functions are automatically smooth.

— 1. Complex differentiation and power series —

Recall in real analysis that if is a function defined on some subset

of the real line

, and

is an interior point of

(that is to say,

contains an interval of the form

for some

), then we say that

is differentiable at

if the limit

exists (note we have to exclude from the possible values of

to avoid division by zero. If

is differentiable at

, we denote the above limit as

or

, and refer to this as the derivative of

at

. If

is open (that is to say, every element of

is an interior point), and

is differentiable at every point of

, then we say that

is differentiable on

, and call

the derivative of

. (One can also define differentiability at non-interior points if they are not isolated, but for simplicity we will restrict attention to interior derivatives only.)

We can adapt this definition to the complex setting without any difficulty:

Definition 2 (Complex differentiability) Let

be a subset of the complex numbers

, and let

be a function. If

is an interior point of

(that is to say,

contains a disk

for some

), we say that

is complex differentiable at

if the limit

exists, in which case we denote this limit as

,

, or

, and refer to this as the complex derivative of

at

. If

is open (that is to say, every point in

is an interior point), and

is complex differentiable at every point at

, we say that

is complex differentiable on

, or holomorphic on

.

In terms of epsilons and deltas: is complex differentiable at

with derivative

if and only if, for every

, there exists

such that

whenever

is such that

. Another way of writing this is that we have an approximate linearisation

as approaches

, where

denotes a quantity of the form

for

in a neighbourhood of

, where

goes to zero as

goes to

. Making the change of variables

, one can also write the derivative

in the familiar form

where is the translation of

by

.

If is differentiable at

, then from the limit laws we see that

and hence

that is to say that is continuous at

. In particular, holomorphic functions are automatically continuous. (Later on we will see that they are in fact far more regular than this, being smooth and even analytic.)

It is usually quite tedious to verify complex differentiability of a function, and to compute its derivative, from first principles. We will give just one example of this:

Proposition 3 Let

be a non-negative integer. Then the function

is holomorphic on the entire complex plane

, with derivative

(with the convention that

is zero when

).

Proof: This is clear for , so suppose

. We need to show that for any complex number

, that

But we have the geometric series identity

which is valid (in any field) whenever , as can be seen either by induction or by multiplying both sides by

and cancelling the telescoping series on the right-hand side. The claim then follows from the usual limit laws.

Fortunately, we have the familiar laws of differential calculus, that allow us to more quickly establish the differentiability of functions if they arise as various combinations of functions that are already known to be differentiable, and to compute the derivative:

Exercise 4 (Laws of differentiation) Let

be an open subset of

, let

be a point in

, and let

be functions that are complex differentiable at

.

- (i) (Linearity) Show that

is complex differentiable at

, with derivative

. For any constant

, show that

is differentiable at

, with derivative

.

- (ii) (Product rule) Show that

is complex differentiable at

, with derivative

.

- (iii) (Quotient rule) If

is non-zero, show that

(which is defined in a neighbourhood of

, by continuity) is complex differentiable at

, with derivative

.

- (iv) (Chain rule) If

is a neighbourhood of

, and

is a function that is complex differentiable at

, show that the composition

(which is defined in a neighbourhood of

) is complex differentiable at

, with derivative

(Hint: take your favourite proof of the real-variable version of these facts and adapt them to the complex setting.)

One could also state and prove a complex-variable form of the inverse function theorem here, but the proof of that statement is a bit more complicated than the ones in the above exercise, so we defer it until later in the course when it becomes needed.

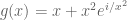

If a function is holomorphic on the entire complex plane, we call it an entire function; clearly such functions remain holomorphic when restricted to any open subset

of the complex plane. Thus for instance Proposition 3 tells us that the functions

are entire, and from linearity we then see that any complex polynomial

will be an entire function, with derivative given by the familiar formula

A function of the form , where

are polynomials with

not identically zero, is called a rational function, being to polynomials as rational numbers are to integers. Such a rational function is well defined as long as

is not zero. From the factor theorem (which works over any field, and in particular over the complex numbers) we know that the number of zeroes of

is finite, being bounded by the degree of

(of course we will be able to say something stronger once we have the fundamental theorem of algebra). Because of these singularities, rational functions are rarely entire; but from the quotient rule we do at least see that

is complex differentiable wherever the denominator is non-zero. Such functions are prime examples of meromorphic functions, which we will discuss later in the course.

Exercise 5 (Gauss-Lucas theorem) Let

be a complex polynomial that is factored as

for some non-zero constant

and roots

(not necessarily distinct) with

.

- (i) Suppose that

all lie in the upper half-plane

. Show that any root of the derivative

also lies in the upper half-plane. (Hint: use the product rule to decompose the log-derivative

into partial fractions, and then investigate the sign of the imaginary part of this log-derivative for

outside the upper half-plane.)

- (ii) Show that all the roots of

lie in the convex hull of the set

of roots of

, that is to say the smallest convex polygon that contains

.

Now we discuss power series, which are infinite degree variants of polynomials, and which turn out to inherit many of the algebraic and analytic properties of such polynomials, at least if one stays within the disk of convergence.

Definition 6 (Power series) Let

be a complex number. A formal power series with complex coefficients around the point

is a formal series of the form

for some complex numbers

, with

an indeterminate.

One can attempt to evaluate a formal power series at a given complex number

by replacing the formal indeterminate

with the complex number

. This may or may not produce a convergent (or absolutely convergent) series, depending on where

is; for instance, the power series

is always absolutely convergent at

, but the geometric power series

fails to be even conditionally convergent whenever

(since the summands do not go to zero). As it turns out, the region of convergence is always essentially a disk, the size of which depends on how rapidly the coefficients

decay (or how slowly they grow):

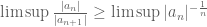

Proposition 7 (Convergence of power series) Let

be a formal power series, and define the radius of convergence

of the series to be the quantity

with the convention that

is infinite if

. (Note that

is allowed to be zero or infinite.) Then the formal power series is absolutely convergent for any

in the disk

(known as the disk of convergence), and is divergent (i.e., not convergent) for any

in the exterior region

.

Proof: The proof is nearly identical to the analogous result for real power series. First suppose that is a complex number with

(this of course implies that

is finite). Then by (3), we have

for infinitely many

, which after some rearranging implies that

for infinitely many

. In particular, the sequence

does not go to zero as

, which implies that

is divergent.

Now suppose that is a complex number with

(this of course implies that

is non-zero). Choose a real number

with

, then by (3), we have

for all sufficiently large

, which after some rearranging implies that

for all sufficiently large . Since the geometric series

is absolutely convergent, this implies that

is absolutely convergent also, as required.

Remark 8 Note that this proposition does not say what happens on the boundary

of this disk (assuming for sake of discussion that the radius of convergence

is finite and non-zero). The behaviour of power series on and near the boundary of the disk of convergence is in fact remarkably subtle; see for instance Example 11 below.

The above proposition gives a “root test” formula for the radius of convergence. The following “ratio test” variant gives convenient lower and upper bounds for the radius of convergence which suffices in many applications:

Exercise 9 (Ratio test) If

is a formal power series with the

non-zero for all sufficiently large

, show that the radius of convergence

of the series obeys the lower bound

In particular, if the limit

exists, then it is equal to

. Give examples to show that strict inequality can hold in either of the bounds in (4). (For an extra challenge, provide an example where both bounds are simultaneously strict.)

If a formal power series has a positive radius of convergence, then it defines a function

in the disk of convergence by setting

We refer to such a function as a power series, and refer to as the radius of convergence of that power series. (Strictly speaking, a formal power series and a power series are different concepts, but there is little actual harm in conflating them together in practice, because of the uniqueness property established in Exercise 17 below.)

Example 10 The formal power series

has a zero radius of convergence, thanks to the ratio test, and so only converges at

. Conversely, the exponential formal power series

has an infinite radius of convergence (thanks to the ratio test), and converges of course to

when evaluated at any complex number

.

Example 11 (Geometric series) The formal power series

has radius of convergence

. If

lies in the disk of convergence

, then we have

and thus after some algebra we obtain the geometric series formula

as long as

is inside the disk

. The function

does not extend continuously to the boundary point

of the disk, but does extend continuously (and even smoothly) to the rest of the boundary, and is in fact holomorphic on the remainder

of the complex plane. However, the geometric series

diverges at every single point of this boundary (when

, the coefficients

of the series do not converge to zero), and of course definitely diverge outside of the disk as well. Thus we see that the function that a power series converges to can extend well beyond the disk of convergence, which thus may only capture a portion of the domain of definition of that function. For instance, if one formally applies (5) with, say,

, one ends up with the apparent identity

This identity does not make sense if one interprets infinite series in the classical fashion, as the series

is definitely divergent. However, by formally extending identities such as (5) beyond their disk of convergence, we can generalise the notion of summation of infinite series to assign meaningful values to such series even if they do not converge in the classical sense. This leads to generalised summation methods such as zeta function regularisation, which are discussed in this previous blog post. However, we will not use such generalised interpretations of summation very much in this course.

Exercise 12 For any complex numbers

, show that the formal power series

has radius of convergence

(with the convention that this is infinite for

), and is equal to the function

inside the disk of convergence.

Exercise 13 For any positive integer

, show that the formal power series

has radius of convergence

, and converges to the function

in the disk

. Here of course

is the usual binomial coefficient.

We have seen above that power series can be well behaved as one approaches the boundary of the disk of convergence, while being divergent at the boundary. However, the converse scenario, in which the power series converges at the boundary but does not behave well as one approaches the boundary, does not occur:

Exercise 14

(i) (Summation by parts formula) Let be a finite sequence of complex numbers, and let

be the partial sums for

. Show that for any complex numbers

, that

(ii) Let be a sequence of complex numbers such that

is convergent (not necessarily absolutely) to zero. Show that for any

, the series

is absolutely convergent, and

(Hint: use summation by parts and a limiting argument to express

in terms of the partial sums

.)

(iii) (Abel’s theorem) Let be a power series with a finite positive radius of convergence

, and let

be a point on the boundary of the disk of convergence at which the series

converges (not necessarily absolutely). Show that

. (Hint: use various translations and rotations to reduce to the case considered in (ii).)

As a general rule of thumb, as long as one is inside the disk of convergence, power series behave very similarly to polynomials. In particular, we can generalise the differentiation formula (2) to such power series:

Theorem 15 Let

be a power series with a positive radius of convergence

. Then

is holomorphic on the disk of convergence

, and the derivative

is given by the power series

that has the same radius of convergence

as

.

Proof: From (3), the standard limit and the usual limit laws, it is easy to see that the power series

has the same radius of convergence

as

. To show that this series is actually the derivative of

, we use first principles. If

lies in the disk of convergence, we consider the Newton quotient

for . Expanding out the absolutely convergent series

and

, we can write

The ratio vanishes for

, and for

it is equal to

as in the proof of Proposition 3. Thus

As approaches

, each summand

converges to

. This almost proves the desired limiting formula

but we need to justify the interchange of a sum and limit. Fortunately we have a standard tool for this, namely the Weierstrass -test (which works for complex-valued functions exactly as it does for real-valued functions; one could also use the dominated convergence theorem here). It will be convenient to select two real numbers

with

. Clearly, for

close enough to

, we have

. By the triangle inequality we then have

On the other hand, from (3) we know that for sufficiently large

, hence

for sufficiently large

. From the ratio test we know that the series

is absolutely convergent, hence the series

is also. Thus, for

sufficiently close to

, the summands

are uniformly dominated by an absolutely summable sequence of numbers

. Applying the Weierstrass

-test (or dominated convergence theorem), we obtain the claim.

Exercise 16 Prove the above theorem directly using epsilon and delta type arguments, rather than invoking the

-test or the dominated convergence theorem.

We remark that the above theorem is a little easier to prove once we have the complex version of the fundamental theorem of calculus, but this will have to wait until the next set of notes, where we will also prove a remarkable converse to the above theorem, in that any holomorphic function can be expanded as a power series around any point in its domain.

A convenient feature of power series is the ability to equate coefficients: if two power series around the same point agree, then their coefficients must also agree. More precisely, we have:

Exercise 17 (Taylor expansion and uniqueness of power series) Let

be a power series with a positive radius of convergence. Show that

, where

denotes the

complex derivative of

. In particular, if

is another power series around

with a positive radius of convergence which agrees with

on some neighbourhood

of

(thus,

for all

), show that the coefficients of

and

are identical, that is to say that

for all

.

Of course, one can no longer compare coefficients so easily if the power series are based around two different points. For instance, from Exercise 11 we see that the geometric series and

both converge to the same function

on the unit disk

, but have differing coefficients. The precise relation between the coefficients of power series of the same function is given as follows:

Exercise 18 (Changing the origin of a power series) Let

be a power series with a positive radius of convergence

. Let

be an element of the disk of convergence

. Show that the formal power series

, where

has radius of convergence at least

, and converges to

on the disk

. Here of course

is the usual binomial coefficient.

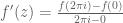

Theorem 15 gives us a rich supply of complex differentiable functions, particularly when combined with Exercise 4. For instance, the complex exponential function

has an infinite radius of convergence, and so is entire, and is its own derivative:

This makes the complex trigonometric functions

entire as well, and from the chain rule we recover the familiar formulae

Of course, one can combine these functions together in many ways to create countless other complex differentiable functions with explicitly computable derivatives, e.g. is an entire function with derivative

, the tangent function

is holomorphic outside of the discrete set

with derivative

, and so forth.

Exercise 19 (Multiplication of power series) Let

and

be power series that both have radius of convergence at least

. Show that on the disk

, we have

where the right-hand side is another power series of radius of convergence at least

, with coefficients

given as the convolution

of the sequences

and

.

— 2. The Cauchy-Riemann equations —

Thus far, the theory of complex differentiation closely resembles the analogous theory of real differentiation that one sees in an introductory real analysis class. But now we take advantage of the Argand plane representation of to view a function

of one complex variable as a function

of two real variables. This gives rise to some further notions of differentiation. Indeed, if

is a function defined on an open subset of

, and

is a point in

, then in addition to the complex derivative

already discussed, we can also define (if they exist) the partial derivatives

and

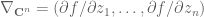

these will be complex numbers if the limits on the right-hand side exist. There is also (if it exists) the gradient (or Fréchet derivative) , defined as the vector

with the property that

where is the Euclidean norm of

.

These notions of derivative are of course closely related to each other. If a function is Fréchet differentiable at

, in the sense that the gradient

exists, then on specialising the limit in (7) to vectors

of the form

or

we see that

and

leading to the familiar formula

for the gradient of a function

that is Fréchet differentiable at

. We caution however that it is possible for the partial derivatives

of a function to exist without the function being Fréchet differentiable, in which case the formula (8) is of course not valid. (A typical example is the function

defined by setting

for

, with

; this function has both partial derivatives

existing at

, but

is not differentiable here.) On the other hand, if the partial derivatives

exist everywhere on

and are additionally known to be continuous, then the fundamental theorem of calculus gives the identity

for and

sufficiently small (with the convention that

if

), and from this it is not difficult to see that

is then Fréchet differentiable everywhere on

.

Similarly, if is complex differentiable at

, then by specialising the limit (6) to variables

of the form

or

for some non-zero real

near zero, we see that

and

leading in particular to the Cauchy-Riemann equations

that must be satisfied in order for to be complex differentiable. More generally, from (6) we see that if

is complex differentiable at

, then

which on comparison with (7) shows that is also Fréchet differentiable with

Finally, if is Fréchet differentiable at

and one has the Cauchy-Riemann equations (9), then from (7) we have

which after making the substitution gives

which on comparison with (6) shows that is complex differentiable with

We summarise the above discussion as follows:

Proposition 20 (Differentiability and the Cauchy-Riemann equations) Let

be an open subset of

, let

be a function, and let

be an element of

.

- (i) If

is complex differentiable at

, then it is also Fréchet differentiable at

, with

In particular, the Cauchy-Riemann equations (9) hold at

.

- (ii) Conversely, if

is Fréchet differentiable at

and obeys the Cauchy-Riemann equations at

, then

is complex differentiable at

.

Remark 21 From part (ii) of the above proposition we see that if

is Fréchet differentiable on

and obeys the Cauchy-Riemann equations on

, then it is holomorphic on

. One can ask whether the requirement of Fréchet differentiability can be weakened. It cannot be omitted entirely; one can show, for instance, that the function

defined by

for non-zero

and

obeys the Cauchy-Riemann equations at every point

, but is not complex differentiable (or even continuous) at the origin. But there is a somewhat difficult theorem of Looman and Menchoff that asserts that if

is continuous on

and obeys the Cauchy-Riemann equations on

, then it is holomorphic. We will not prove or use this theorem in this course; generally in modern applications, when one wants to weaken the regularity hypotheses of a theorem involving classical differentiation, the best way to do so is to replace the notion of a classical derivative with that of a weak derivative, rather than insist on computing derivatives in the classical pointwise sense. See this blog post for more discussion.

Combining part (i) of the above proposition with Theorem 15, we also conclude as a corollary that any power series will be smooth inside its disk of convergence, in the sense all partial derivatives to all orders of this power series exist.

Remark 22 From the geometric perspective, one can interpret complex differentiability at a point

as a requirement that a map

is conformal and orientation-preserving at

, at least in the non-degenerate case when

is non-zero. In more detail: suppose that

is a map that is complex differentiable at some point

with

. Let

be a differentiable curve with

; we view this as the trajectory of some particle which passes through

at time

. The derivative

(defined in the usual manner by limits of Newton quotients) can then be viewed as the velocity of the particle as it passes through

. The map

takes this particle to a new particle parameterised by the curve

; at time

, this new particle passes through

, and by the chain rule we see that the velocity of the new particle at this time is given by

Thus, if we write

in polar coordinates as

, the map

transforms the velocity of the particle by multiplying the speed by a factor of

and rotating the direction of travel counter-clockwise by

. In particular, we consider two differentiable trajectories

both passing through

at time

(with non-zero speeds), then the map

preserves the angle between the two velocity vectors

, as well as their orientation (e.g. if

is counterclockwise to

, then

is counterclockwise to

. This is in contrast to, for instance, shear transformations such as

, which preserve orientation but not angle, or the complex conjugation map

, which preserve angle but not orientation. The same preservation of angle is present for real differentiable functions

on an interval

, but is much less impressive in that case since the only angles possible between two vectors on the real line are

and

; it is the geometric two-dimensionality of the complex plane that makes conformality a much stronger and more “rigid” property for complex differentiable functions.

One consequence of the first component of Proposition 20(i) is that the complex notion of differentiation and the real notion of differentiation are compatible with each other. More precisely, if

is holomorphic and

is the restriction of

to the real line, then the real derivative

of

exists and is equal to the restriction of the complex derivative

to the real line. For instance, since

for a complex variable

, we also have

for a real variable

. For similar reasons, it will be a safe “abuse of notation” to use the notation

both to refer to the complex derivative of a function

, and also the real derivative of the restriction of that function to the real line.

If one breaks up a complex function into real and imaginary parts

for some

, then on taking real and imaginary parts one can express the Cauchy-Riemann equations as a system

of two partial differential equations for two functions . This gives a quick way to test if various functions are differentiable. Consider for instance the conjugation function

. In this case,

and

. These functions, being polynomial in

, is certainly Fréchet differentiable everywhere; the equation (11) is always satisfied, but the equation (10) is never satisfied. As such, the conjugation function is never complex differentiable. Similarly for the real part function

, the imaginary part function

, or the absolute value function

. The function

has real part

and imaginary part

; one easily checks that the system (10), (11) is only satisfied when

, so this function is only complex differentiable at the origin. In particular, it is not holomorphic on any non-empty open set.

The general rule of thumb that one should take away from these examples is that complex functions that are constructed purely out of “good” functions such as polynomials, the complex exponential, complex trigonometric functions, or other convergent power series are likely to be holomorphic, whereas functions that involve “bad” functions such as complex conjugation, the real and imaginary part, or the absolute value, are unlikely to be holomorphic.

Exercise 23 (Wirtinger derivatives) Let

be an open subset of

, and let

be a Fréchet differentiable function. Define the Wirtinger derivatives

,

by the formulae

- (i) Show that

is holomorphic on

if and only if the Wirtinger derivative

vanishes identically on

.

- (ii) If

is given by a polynomial

in both

and

for some complex coefficients

and some natural number

, show that

and

(Hint: first establish a Leibniz rule for Wirtinger derivatives.) Conclude in particular that

is holomorphic if and only if

vanishes whenever

(i.e.

does not contain any terms that involve

).

- (iii) If

is a point in

, show that one has the Taylor expansion

as

, where

denotes a quantity of the form

, where

goes to zero as

goes to

(compare with (1)). Conversely, show that this property determines the numbers

and

uniquely (and thus can be used as an alternate definition of the Wirtinger derivatives).

Remark 24 Any polynomial

in the real and imaginary parts

of

can be rewritten as a polynomial in

and

as per (17), using the usual identities

for

. Thus such a non-holomorphic polynomial of one complex variable

can be viewed as the restriction of a holomorphic polynomial

of two complex variables

to the anti-diagonal

, and the Wirtinger derivatives can then be interpreted as genuine (complex) partial derivatives in these two complex variables. More generally, Wirtinger derivatives are convenient tools in the subject of several complex variables, which we will not cover in this course.

The Cauchy-Riemann equations couple the real and imaginary parts of a holomorphic function to each other. But it is also possible to eliminate one of these components from the equations and obtain a constraint on just the real part

, or just the imaginary part

. Suppose for the moment that

is a holomorphic function which is twice continuously differentiable (thus the second partial derivatives

,

,

,

all exist and are continuous on

); we will show in the next set of notes that this extra hypothesis is in fact redundant. Assuming continuous second differentiability for now, we have Clairaut’s theorem

everywhere on . Similarly for the real and imaginary parts

. If we then differentiate (10) in the

direction, (11) in the

direction, and then sum, the derivatives of

cancel thanks to Clairaut’s theorem, and we obtain Laplace’s equation

which is often written more compactly as

where is the Laplacian operator

A similar argument gives ; by linearity we then also have

.

Functions for which

is continuously twice differentiable and

are known as harmonic functions: thus we have shown that (continuously twice differentiable) holomorphic functions are automatically harmonic, as are the real and imaginary parts of such functions. The converse is not true: not every harmonic function

is holomorphic. For instance, the conjugate function

is clearly harmonic on

, but not holomorphic. We will return to the precise relationship between harmonic and holomorphic functions shortly.

Harmonic functions have many remarkable properties. Since the second derivative in a given direction is a local measure of “convexity” of a function, we see from (13) that any convex behaviour of a harmonic function in one direction has to be balanced by an equal and opposite amount of concave behaviour in the orthogonal direction. A good example of a harmonic function to keep in mind is the function

which exhibits convex behavior in and concave behavior in

in exactly opposite amounts. This function is the real part of the holomorphic function

, which is of course consistent with the previous observation that the real parts of holomorphic functions are harmonic.

We will discuss harmonic functions more in later notes. For now, we record just one important property of these functions, namely the maximum principle:

Theorem 25 (Maximum principle) Let

be an open subset of

, and let

be a harmonic function. Let

be a compact subset of

, and let

be the boundary of

. Then

Informally, the maximum principle asserts that the maximum of a real-valued harmonic function on a compact set is always attained on the boundary, and similarly for the minimum. In particular, any bound on the harmonic function that one can obtain on the boundary is automatically inherited by the interior. Compare this with a non-harmonic function such as , which is bounded by

on the boundary of the compact unit disk

, but is not bounded by

on the interior of this disk.

Proof: We begin with an “almost proof” of this principle, and then repair this attempted proof so that it is an actual proof.

We will just prove (14), as (15) is proven similarly (or one can just observe that if is harmonic then so is

). Clearly we have

so the only scenario that needs to be excluded is when

Suppose that this is the case. As is continuous and

is compact,

must attain its maximum at some point

in

; from (16) we see that

must be an interior point. Since

is a local maximum of

, and

is twice differentiable, we must have

and similarly

This almost, but does not quite, contradict the harmonicity of , since it is still possible that both of these partial derivatives vanish. To get around this problem we use the trick of creating an epsilon of room, adding a tiny bit of convexity to

. Let

be a small number to be chosen later, and let

be the modified function

Since is compact, the function

is bounded on

. Thus, from (16), we see that if

is small enough we have

Arguing as before, must attain its maximum at some interior point

of

, and so we again have

and similarly

On the other hand, since is harmonic, we have

on . These facts contradict each other, and we are done.

Exercise 26 (Maximum principle for holomorphic functions) If

is a continuously twice differentiable holomorphic function on an open set

, and

is a compact subset of

, show that

(Hint: use Theorem 25 and the fact that

for any complex number

. You may find the proof of Lemma 8 in the next set of notes to be helpful as inspiration.) What happens if we replace the suprema on both sides by infima? This result is also known as the maximum modulus principle.

Exercise 27 Recall the Wirtinger derivatives defined in Exercise 23(i).

- (i) If

is twice continuously differentiable on an open subset

of

, show that

Use this to give an alternate proof that (

) holomorphic functions are harmonic.

- (ii) If

is given by a polynomial

in both

and

for some complex coefficients

and some natural number

, show that

is harmonic on

if and only if

vanishes whenever

and

are both positive (i.e.

only contains terms

or

that only involve one of

or

).

- (iii) If

is a real polynomial

in

and

for some real coefficients

and some natural number

, show that

is harmonic if and only if it is the real part of a polynomial

of one complex variable

.

We have seen that the real and imaginary parts of any holomorphic function

are harmonic functions. Conversely, let us call a harmonic function

a harmonic conjugate of another harmonic function

if

is holomorphic on

; this is equivalent by Proposition 20 to

satisfying the Cauchy-Riemann equations (10), (11). Here is a short table giving some examples of harmonic conjugates:

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

(for the last example one of course has to exclude the origin from the domain ).

From Exercise 27(ii) we know that every harmonic polynomial has at least one harmonic conjugate; it is natural to ask whether the same fact is true for more general harmonic functions than polynomials. In the case that the domain is the entire complex plane, the answer is affirmative:

Proposition 28 Let

be a harmonic function. Then there exists a harmonic conjugate

of

. Furthermore, this harmonic conjugate is unique up to constants: if

are two harmonic conjugates of

, then

is a constant function.

Proof: We first prove uniqueness. If is a harmonic conjugate of

, then from the fundamental theorem of calculus, we have

and hence by the Cauchy-Riemann equations (10), (11) we have

Similarly for any other harmonic conjugate of

. It is now clear that

and

differ by a constant.

Now we prove existence. Inspired by the above calculations, we define to be the define

explicitly by the formula

From the fundamental theorem of calculus, we see that is differentiable in the

direction with

This is one of the two Cauchy-Riemann equations needed. To obtain the other one, we differentiate (18) in the variable. The fact that

is continuously twice differentiable allows one to differentiate under the integral sign (exercise!) and conclude that

As is harmonic, we have

, so by the fundamental theorem of calculus we conclude that

Thus we now have both of the Cauchy-Riemann equations (10), (11) in . Differentiating these equations again, we conclude that

is twice continuously differentiable, and hence by Proposition 20 we have

holomorphic on

, giving the claim.

The same argument would also work for some other domains than , such as rectangles

. To handle the general case, though, it becomes convenient to introduce the notion of contour integration, which we will do in the next set of notes. In some cases (specifically, when the underlying domain

fails to be simply connected), it will turn out that some harmonic functions do not have conjugates!

Exercise 29 Show that an entire function

can be real-valued on

only if it is constant.

Exercise 30 Let

be a complex number. Show that if

is an entire function such that

for all

, then

for all

.

80 comments

Comments feed for this article

23 September, 2016 at 1:16 am

g

Typo in exercise 13: you have a fraction instead of a binomial coefficient. (Either that or there’s a TeX rendering bug somewhere.)

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

23 September, 2016 at 1:34 am

Sébastien Boisgérault

Could you categorize this document as “246A — complex analysis” ?

(otherwise it won’t be listed in ).

Regards, SB.

[Done, thanks – T.]

23 September, 2016 at 4:55 am

Anonymous

In exercise 5(ii), it seems that the convex hull of the roots of is the smallest possible convex set containing the roots of

is the smallest possible convex set containing the roots of  if and only if

if and only if  has multiple(!) roots on all the vertices of the convex hull of its roots.

has multiple(!) roots on all the vertices of the convex hull of its roots.

23 September, 2016 at 5:03 am

Anonymous

In the second line of definition 6, “is” is missing before “a formal”.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

23 September, 2016 at 5:06 am

Jhon Manugal

I would hardly debate the Maximum principle as stated here and yet it has such profound consequences. I never quite see it coming. It is a bit like following a game of 3 card monte.

23 September, 2016 at 6:12 am

Anonymous

In remark 21, it seems that should be

should be  for

for  (in order to be smooth on the real and imaginary axes.)

(in order to be smooth on the real and imaginary axes.)

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

23 September, 2016 at 6:50 am

Dirk

When reading the notes, it appeared to my that the fact that holomorphic functions are so rigid can be seen also (and probably most clearly) in the formulation of complex differentiability by linearization: If we view as mapping from

as mapping from  to itself, we would allow for an arbitrary linear map as derivative. However, we view

to itself, we would allow for an arbitrary linear map as derivative. However, we view  as map from

as map from  to itself and only allow for very special linear maps, namely those given by complex multiplication. This greatly restricts the class of linear maps that are allowed to use for linearization, namely to

to itself and only allow for very special linear maps, namely those given by complex multiplication. This greatly restricts the class of linear maps that are allowed to use for linearization, namely to  matrices which have constant diagonal and are skew symmetric. As far as I remember, I haven’t seen this view in any textbook – do you know any book where complex differentiability is discussed this way?

matrices which have constant diagonal and are skew symmetric. As far as I remember, I haven’t seen this view in any textbook – do you know any book where complex differentiability is discussed this way?

[Ah, I had forgotten to add a remark on precisely this; done so now. I think this is discussed for instance in Ahlfors’ book. -T.]

23 September, 2016 at 8:35 am

Anonymous

In exercise 26(ii), it seems that “whenever ” should be “whenever

” should be “whenever  or

or  “.

“.

[Remark clarified – T.]

23 September, 2016 at 10:10 pm

Anonymous

Dear Terry,

I am a female teacher of math.Iam 32.Iam still alone.I admire and like(even I love you,but what a pity you have got married).I always care and follow you,I wonder that this september(nearly end of 2016 ),I do not still your breakththrough,while every year your name attached with great events(2013-Terry Tao and Twin primes,2014-Terry Tao and Navier Stokes,2015-Terry Tao and Erdos problem,2016-?????)

Best wishes,

Natasha,

23 September, 2016 at 11:09 pm

Anonymous

Suppose that is any(!) local coordinate system for a neighborhood of the origin in

is any(!) local coordinate system for a neighborhood of the origin in  , is it possible by defining

, is it possible by defining  to develop a completely analogous theory for holomorphic and analytic functions with respect to the complex variable

to develop a completely analogous theory for holomorphic and analytic functions with respect to the complex variable  ?

?

24 September, 2016 at 9:35 am

Terence Tao

Certainly! Of course, the underlying vector space, topological, or smooth structure of may have little to do with the complex structure thus created if the local coordinate system used is nonlinear, discontinuous, or non-smooth respectively.

may have little to do with the complex structure thus created if the local coordinate system used is nonlinear, discontinuous, or non-smooth respectively.

24 September, 2016 at 12:55 pm

Anonymous

As a nice application, suppose that the new coordinates are sufficiently smooth functions of the (“reference”) coordinates

are sufficiently smooth functions of the (“reference”) coordinates  (e.g.

(e.g.  with nonsingular Jacobian matrix near the origin) and

with nonsingular Jacobian matrix near the origin) and  are also smooth functions of

are also smooth functions of  . Then to check if the complex variable $w’ = u’ + v’$ can be represented as a power series of $z’ = x’ + i y’$ near the origin, one needs only to check if

. Then to check if the complex variable $w’ = u’ + v’$ can be represented as a power series of $z’ = x’ + i y’$ near the origin, one needs only to check if  satisfy the Cauchy-Riemann equations (with respect to

satisfy the Cauchy-Riemann equations (with respect to  ) near the origin.

) near the origin.

24 September, 2016 at 1:04 pm

Anonymous

Correction: it should be

26 September, 2016 at 2:52 am

Anonymous

Remark 21 : There seems to be a missing link under “this blog post”

A bit later : “\href{harmonic conjugate}” should probably link to something as well.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

26 September, 2016 at 5:39 pm

Steven Gubkin

I remember being frustrated by the definition of Wirtinger derivatives when I was learning this subject. Two points which might be helpful:

Any real linear map can be uniquely decomposed into a complex linear map and a complex antilinear map. When you apply this to the real linear derivative of a complex function

can be uniquely decomposed into a complex linear map and a complex antilinear map. When you apply this to the real linear derivative of a complex function  at a point

at a point  , you obtain exactly the formulas for the Wirtinger derivatives:

, you obtain exactly the formulas for the Wirtinger derivatives:  .

.

Another thing: the Wirtinger derivatives are perhaps more clearly written as

and

[Good suggestions, I have added them to the text – T.]

27 September, 2016 at 6:01 am

Anonymous

Typo in the delta-epsilon definition near beginning: should say |z – z0| < delta.

Thanks for making these notes!

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

27 September, 2016 at 10:58 am

Anonymous

It seems that in exercise 26 (and also in theorem 25), one can assume (without loss of generality) that is closed (not necessarily compact), since by appropriate bilinear transformation it can be mapped to a compact set.

is closed (not necessarily compact), since by appropriate bilinear transformation it can be mapped to a compact set.

27 September, 2016 at 11:22 am

Terence Tao

This is only true if one works in the Riemann sphere (with its attendant topological and complex structures), which is where bilinear transformations live as complex automorphisms. Otherwise there are many counterexamples, e.g. is unbounded on the upper half-plane, but is bounded on the boundary of that half-plane. (See however the Phragmen-Lindelof principle for an important partial result in this direction.)

is unbounded on the upper half-plane, but is bounded on the boundary of that half-plane. (See however the Phragmen-Lindelof principle for an important partial result in this direction.)

1 October, 2016 at 9:38 pm

Anonymous

Hello professor, for the ratio test (Ex 9), we also have , right? Thank you for your time.

, right? Thank you for your time.

2 October, 2016 at 9:05 am

Math 246A, Notes 3: Cauchy’s theorem and its consequences | What's new

[…] this and Proposition 7 of Notes 1, we see that the radius of convergence of is indeed at least […]

9 October, 2016 at 4:13 am

Fred Lunnon

Following equn. (8) —

for “existing at {z_0}, but {f} is not differentiable here”

read “existing at {z_0 = 0}, but {f} is not differentiable here”

prop. 20, remark 21 — “Fréchet” (3 times)

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

12 October, 2016 at 2:00 pm

Anonymous

May be in Proposition 20 “ ” and “

” and “ be an element of

be an element of  .” are typos and they should be “

.” are typos and they should be “ ” and “element of

” and “element of  “.

“.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

18 October, 2016 at 9:32 pm

246A, Notes 5: conformal mapping | What's new

[…] Exercise 2 Establish Lemma 1(ii) by direct calculation, avoiding the use of holomorphic functions. (Hint: the calculations are cleanest if one uses Wirtinger derivatives, as per Exercise 27 of Notes 1.) […]

23 December, 2016 at 5:27 am

Venky

Great notes! Two typos: in the proof of Proposition 7, there is a badly formed expression , and there is an extra

, and there is an extra  in the equation right after equation (18).

in the equation right after equation (18).

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

12 February, 2017 at 5:27 am

Anonymous

There is also (if it exists) the gradient (or Fréchet derivative) {Df(z_0) \in {\bf C}^2}, defined as the vector {(D_1 f(z_0), D_2 f(z_0)) \in {\bf C}^2} with the property that…

Should be

be  instead? I cannot make sense of this part.

instead? I cannot make sense of this part.

12 February, 2017 at 9:06 am

Terence Tao

No, I intend to lie in

to lie in  (thus each of the components

(thus each of the components  ,

,  of this vector are complex numbers). For instance, if

of this vector are complex numbers). For instance, if  and

and  , then

, then  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

12 February, 2017 at 9:54 am

Anonymous

Ah. When you define ,

,  and

and  are used without having a definition… And later, it is said that

are used without having a definition… And later, it is said that

we see that

and

This looks circular. Would you please elaborate what definition do you use for and

and  ?

?

12 February, 2017 at 12:31 pm

nightmartyr

12 February, 2017 at 2:56 pm

Anonymous

Maybe typos in (7). and

and  should be

should be  and

and  I think.

I think.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

5 June, 2017 at 10:04 am

Five-Value Theorem of Nevanlinna – Elmar Klausmeier's Weblog

[…] 246A, Notes 1: complex differentiation […]

4 September, 2017 at 4:45 am

Anonymous

Do we have the mean value theorem and L’Hopital rule as in real analysis?

4 September, 2017 at 7:12 pm

Terence Tao

L’Hopital’s rule carries over (with basically the same proof), but the mean value theorem is now false. For instance, if is the exponential function, there is no complex number

is the exponential function, there is no complex number  for which

for which  , despite

, despite  being complex differentiable on the entire complex plane. (It is instructive to figure out what property of the real line, that is not shared by the complex numbers, is responsible for the mean value theorem being true for real-valued functions but not complex-valued functions. It is a good exercise to revisit the proof of the real-variable mean value theorem to answer this question.)

being complex differentiable on the entire complex plane. (It is instructive to figure out what property of the real line, that is not shared by the complex numbers, is responsible for the mean value theorem being true for real-valued functions but not complex-valued functions. It is a good exercise to revisit the proof of the real-variable mean value theorem to answer this question.)

5 September, 2017 at 4:07 am

Anonymous

I’m a bit confused with the L’Hopital rule. Rudin gave an example that with

with  and

and  and

and

Is this a contradiction to the L’Hopital rule in complex analysis?

5 September, 2017 at 12:42 pm

Terence Tao

Hmm, you’re right. The argument I had in mind assumed that the denominator was analytic at the limit point, which is not the case in Rudin’s example.

3 November, 2017 at 6:20 am

Cong Ma

I wonder whether the mean value theorem carries over to the Wirtinger derivative. That is for , do we have

, do we have ![f(z_1)-f(z_2) = \int_{0}^{1}\nabla f(z(\tau))d\tau \left[\begin{array}{c} z_{1}-z_{2}\\ \overline{z_{1}-z_{2}} \end{array}\right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=f%28z_1%29-f%28z_2%29+%3D+%5Cint_%7B0%7D%5E%7B1%7D%5Cnabla+f%28z%28%5Ctau%29%29d%5Ctau+%5Cleft%5B%5Cbegin%7Barray%7D%7Bc%7D+z_%7B1%7D-z_%7B2%7D%5C%5C+%5Coverline%7Bz_%7B1%7D-z_%7B2%7D%7D+%5Cend%7Barray%7D%5Cright%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) , where

, where  ,

,  denotes the conjugate of

denotes the conjugate of  and

and  is the Wirtinger Jacobian.

is the Wirtinger Jacobian.

7 November, 2017 at 4:03 pm

Terence Tao

This identity is true (for continuously differentiable functions ), as can be seen from the fundamental theorem of calculus and the chain rule, but I am not sure if it deserves to be named the mean value theorem.

), as can be seen from the fundamental theorem of calculus and the chain rule, but I am not sure if it deserves to be named the mean value theorem.

7 November, 2017 at 4:47 pm

Cong Ma

Thank you very much!

7 October, 2020 at 8:18 pm

adityaguharoy

Does the mean value theorem fail mainly because we don’t have an ordering of the complex numbers anymore, and so things like the intermediate value property or Rolle’s theorem fail.

In other words, we cannot say that the derivative is zero at a point of extremum because now the extremum doesn’t make sense for a complex valued function anymore.

Is that correct ?

[Yes – T.]

4 September, 2017 at 10:40 pm

Fan

Probably there is a type in Exercise 29 “can real-valued”.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

11 March, 2018 at 4:01 pm

James Fullwood

In the definition of radius of convergence, should lim inf be replaced with lim sup? (If not, then I am curious as to why most references use lim sup.)

11 March, 2018 at 8:59 pm

Terence Tao

One can write the radius of convergence either as the limit inferior of , or as the reciprocal of the limit superior of

, or as the reciprocal of the limit superior of  ; the two definitions are equivalent.

; the two definitions are equivalent.

27 June, 2018 at 7:42 am

অরিত্র

There’s a typo in exercise 4(iv): the g’s should be replaced by h

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

1 July, 2018 at 6:13 am

Aritra Bhattacharya

What is that in line 3 of proof of proposition 7?

in line 3 of proof of proposition 7?

[HTML formatting error; should be fixed now – T.]

16 November, 2018 at 6:29 am

Aritra Biswas

Respected Sir,

As you mention in the ‘power Series’ section “As it turns out, the region of convergence is always essentially a disk”, I am wandering as to why the region of convergence is essentially a disk and nothing else, i.e I am curious to know if there is any topological subtle reason for such uniform behavior of the region of convergence. Since I am a new-learner, it may happen that my question bears some logical error or pointless per se. I am apologetic beforehand for such occurrences. Pleasr help me go through.

Thank you.

21 November, 2018 at 2:52 pm

Terence Tao

The fact that the region of convergence is a disk (possibly with or without portions of the circular boundary of the disk) is a corollary of the root test. It reflects the fact that if a series converges conditionally, then any other series with exponentially smaller summands will converge absolutely.

5 December, 2018 at 11:07 pm

Aritra Biswas

Thank you Sir. Thanks a lot.

23 December, 2018 at 4:56 pm

keej

Thank you for posting these notes. I have a question (possible typo?)

In Remark 22, regarding the statement “The same preservation of angle is present for real differentiable functions”, do you mean functions from complex numbers to reals, as written, or do you mean functions from reals to reals? If the former, I’m not sure how to interpret what it means for such a map to be conformal.

23 December, 2018 at 10:17 pm

Terence Tao

I meant the latter; I have modified the text to clarify this.

6 April, 2020 at 4:44 am

Maxis Jaisi

I’ve never seen gradient defined for a complex valued function. How do you define the gradient of a map , for example?

, for example?

6 April, 2020 at 9:16 am

Terence Tao

There would be two possible gradients one could use here. In analogy to the gradient used in these notes, one could define the gradient

used in these notes, one could define the gradient  of a continuously (real) differentiable

of a continuously (real) differentiable  by identifying

by identifying  with

with  and taking the usual real gradient. If the function

and taking the usual real gradient. If the function  depends holomorphically on its inputs

depends holomorphically on its inputs  (or equivalently if

(or equivalently if  obeys the Cauchy-Riemann equations in each variable separately), one can also define the complex gradient

obeys the Cauchy-Riemann equations in each variable separately), one can also define the complex gradient  as

as  .

.

7 October, 2020 at 2:42 am

Jiayun Meng

At the beginning of section two, shall the denominator of partial derivative in direction of y be ih instead of h?

7 October, 2020 at 3:30 am

Jiayun Meng

Sorry! I understood the material wrongly. It should be h. But I am a bit confused about why it is defined like this. Can I view it as the partial derivative in sense of R^2 plane? Thanks in advance!

12 October, 2020 at 2:36 pm

Ben Johnsrude

Yes, it’s just a partial derivative in the usual sense of a function on R^2 (taking values in the complex plane), the vertical partial derivative. – Ben

7 October, 2020 at 7:58 pm

adityaguharoy

Yesterday during the lectures the following question was asked :

“Does there exist a function which satisfies the Cauchy Riemann equations at a point but is not holomorphic there ?”

The answer is yes (as we all agreed), and here is an example (I will leave the verification for the reader) :

The function satisfies the Cauchy Riemann conditions at

satisfies the Cauchy Riemann conditions at  but is NOT holomorphic there.

but is NOT holomorphic there.

The easiest way to verify is to go via the definition of complex differentiability to verify that is indeed not holomorphic at 0, and the Cauchy Riemann conditions can be verified in a straightforward manner.

is indeed not holomorphic at 0, and the Cauchy Riemann conditions can be verified in a straightforward manner.

7 October, 2020 at 8:05 pm

adityaguharoy

I just forgot to mention that we should have in the above example.

in the above example.

7 October, 2020 at 10:53 pm

Prateek P Kulkarni

Well,it was me who asked the question. My question wasn’t exactly about one point, but your answer has got it all. Thanks for the examples @adityaguharoy

9 October, 2020 at 10:17 am

Anonymous

There are three notions of differentiability at a point in this set of notes and Stein-Shakarchi’s book.

in this set of notes and Stein-Shakarchi’s book.

(I) The “gradient” (or Fréchet derivative) , defined as the vector

, defined as the vector  with the property that

with the property that

where is the Euclidean norm of

is the Euclidean norm of  .

.

In this definition, .

.

(II) The complex derivative in Definition 2.

In this definition is a

is a  -linear map from

-linear map from  to

to  .

.

(III) In Stein-Shakarchi, the complex-valued function is associated with the mapping

is associated with the mapping  where

where  . In this definition,

. In this definition,  is a

is a  -linear map from

-linear map from  to

to  .

.

Are the notions in (I) and (III) equivalent?

9 October, 2020 at 10:51 am

Terence Tao

Yes; the linear map in (III) corresponds in the notation of (I) to the map

in (III) corresponds in the notation of (I) to the map  (identifying

(identifying  with

with  as necessary).

as necessary).

9 October, 2020 at 1:46 pm

Anonymous

Ah. I was confused when trying to identify in notion (I) with the

in notion (I) with the  -linear map

-linear map  in notion (III).

in notion (III).

So the map is a

is a  -linear map from

-linear map from  to

to  , not

, not  to

to  . The

. The  dimensions then match in the two notions.

dimensions then match in the two notions.

9 October, 2020 at 4:22 pm

Anonymous

Maybe it is better to mention that the Fréchet differentiable defined in part two is the real Fréchet differentiable which is a generalization real differentiable so it is weaker than complex differentiable. Nevertheless the complex Fréchet differentiability of a function from to

to  is exactly the complex differentiability in Definition 2 and same for the derivative because complex Fréchet derivative is a generalization of complex derivative.

is exactly the complex differentiability in Definition 2 and same for the derivative because complex Fréchet derivative is a generalization of complex derivative.

12 October, 2020 at 9:59 am

Anonymous

Can one adapt the proof of Theorem 25 to show the strong version of the maximum principle?

12 October, 2020 at 10:16 am

Terence Tao

Hmm, with a fair amount of additional effort, yes, but I don’t know of a proof of comparable length to this one. (At a bare minimum, one now has to use the fact that the domain is connected.) If one has an additional tool such as the mean value theorem or Harnack’s inequality then it is straightforward, but the “first principles” proofs I am aware of are somewhat lengthy.

14 October, 2020 at 7:29 am

Anonymous

I am confused by the statement has partial derivatives

has partial derivatives  and

and  exist at f(0). Aren’t they both 0/0?

exist at f(0). Aren’t they both 0/0?

14 October, 2020 at 10:47 am

Terence Tao

No; try computing the partial derivatives from first principles.

14 October, 2020 at 11:22 am

Anonymous

Thank you! Now that makes sense. Why do the two processes give different results?

14 October, 2020 at 12:24 pm

Anonymous

Because partial derivatives need not be the same.

14 October, 2020 at 6:24 pm

max_principle

In the proof of maximum principle, we have , clearly .why?

.why?

15 October, 2020 at 8:45 am

Anonymous

K is compact, so attains its sup (either in interior of K or on boundary of K). Think of it as a generalization of Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem.

15 October, 2020 at 10:40 am

Anonymous

Simply because is a subset of

is a subset of  .

.

16 October, 2020 at 5:06 pm

Anonymous

In the proof of Theorem 15, as , you said each summand converges to

, you said each summand converges to  . Where does the

. Where does the  come from? I thought it is just

come from? I thought it is just  .

.

[Here the summand refers to the summand of the series . (The summand is itself a sum of

. (The summand is itself a sum of  sub-summands, each of which converge individually to

sub-summands, each of which converge individually to  .) -T]

.) -T]

25 October, 2020 at 6:16 am

Anonymous

In the proof Proposition 28,

… The fact that

I think here “ ” should be “

” should be “ ” since one is not defining the partial derivative on the left but concluding it from (18).

” since one is not defining the partial derivative on the left but concluding it from (18).

[Corrected – T.]

13 December, 2020 at 5:50 pm

Anonymous

The Newton quotient is also used in the proof of Theorem 27 and 30 (the two fundamental theorems of calculus) in Notes 2. Instead of proving from the first principle as in this set of notes, can one somehow use the FTCs to show Theorem 15 in a non-circular way? (It seems that Theorem 15 has been used in various places in later notes.)

[Yes, this is possible, and I encourage you to work out this as an exercise -T.]

13 December, 2020 at 6:00 pm

Anonymous

As

should be

… converges to

This almost proves the desired limiting formula

but we need to justify the interchange of a sum and limit.

The right-hand side should be ?

?

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

23 January, 2021 at 12:56 pm

246B, Notes 2: Some connections with the Fourier transform | What's new

[…] maximum modulus principle (Exercise 26 from 246A Notes 1) for holomorphic functions asserts that if a function continuous on a compact subset of the plane […]

27 September, 2021 at 8:59 am

246A, Notes 0: the complex numbers | What's new

[…] Next set of notes: Notes 1. […]

27 September, 2021 at 9:02 am

246A, Notes 2: complex integration | What's new

[…] set of notes: Notes 1. Next set of notes: Notes […]

10 January, 2022 at 6:48 am

kirtanvora

There’s a typo in a paragraph after exercise 17, 2^{n-1} should be 2^{n+1}

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

27 December, 2022 at 5:42 am

Anonymous

By Exercise 17, given a sequence , if

, if  is a power series with a positive radius of convergence, then

is a power series with a positive radius of convergence, then  for all

for all  . If the mentioned power series fails to have a positive radius of convergence, can one still construct a smooth function

. If the mentioned power series fails to have a positive radius of convergence, can one still construct a smooth function  with

with  for all

for all  ?

?

31 December, 2022 at 7:03 pm

Terence Tao

For real-variable functions, this is the zero-dimensional case of Borel’s lemma. For complex-variable functions, it hinges on what you mean by “smooth”. Functions that are complex differentiable in a neighbourhood of are analytic and so the Taylor series has to have a positive radius of convergence.

are analytic and so the Taylor series has to have a positive radius of convergence.

29 December, 2022 at 7:12 am

Anonymous

Some part of the formula is missing in (7)

[Changed to

to  -T.]

-T.]