Suppose we have a large number of scalar random variables , which each have bounded size on average (e.g. their mean and variance could be

). What can one then say about their sum

? If each individual summand

varies in an interval of size

, then their sum of course varies in an interval of size

. However, a remarkable phenomenon, known as concentration of measure, asserts that assuming a sufficient amount of independence between the component variables

, this sum sharply concentrates in a much narrower range, typically in an interval of size

. This phenomenon is quantified by a variety of large deviation inequalities that give upper bounds (often exponential in nature) on the probability that such a combined random variable deviates significantly from its mean. The same phenomenon applies not only to linear expressions such as

, but more generally to nonlinear combinations

of such variables, provided that the nonlinear function

is sufficiently regular (in particular, if it is Lipschitz, either separately in each variable, or jointly in all variables).

The basic intuition here is that it is difficult for a large number of independent variables to “work together” to simultaneously pull a sum

or a more general combination

too far away from its mean. Independence here is the key; concentration of measure results typically fail if the

are too highly correlated with each other.

There are many applications of the concentration of measure phenomenon, but we will focus on a specific application which is useful in the random matrix theory topics we will be studying, namely on controlling the behaviour of random -dimensional vectors with independent components, and in particular on the distance between such random vectors and a given subspace.

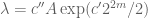

Once one has a sufficient amount of independence, the concentration of measure tends to be sub-gaussian in nature; thus the probability that one is at least standard deviations from the mean tends to drop off like

for some

. In particular, one is

standard deviations from the mean with high probability, and

standard deviations from the mean with overwhelming probability. Indeed, concentration of measure is our primary tool for ensuring that various events hold with overwhelming probability (other moment methods can give high probability, but have difficulty ensuring overwhelming probability).

This is only a brief introduction to the concentration of measure phenomenon. A systematic study of this topic can be found in this book by Ledoux.

— 1. Linear combinations, and the moment method —

We begin with the simple setting of studying a sum of random variables. As we shall see, these linear sums are particularly amenable to the moment method, though to use the more powerful moments, we will require more powerful independence assumptions (and, naturally, we will need more moments to be finite or bounded). As such, we will take the opportunity to use this topic (large deviation inequalities for sums of random variables) to give a tour of the moment method, which we will return to when we consider the analogous questions for the bulk spectral distribution of random matrices.

In this section we shall concern ourselves primarily with bounded random variables; in the next section we describe the basic truncation method that can allow us to extend from the bounded case to the unbounded case (assuming suitable decay hypotheses).

The zeroth moment method gives a crude upper bound when is non-zero,

but in most cases this bound is worse than the trivial bound . This bound, however, will be useful when performing the truncation trick, which we will discuss below.

The first moment method is somewhat better, giving the bound

which when combined with Markov’s inequality gives the rather weak large deviation inequality

As weak as this bound is, this bound is sometimes sharp. For instance, if the are all equal to a single signed Bernoulli variable

, then

, and so

, and so (2) is sharp when

. The problem here is a complete lack of independence; the

are all simultaneously positive or simultaneously negative, causing huge fluctuations in the value of

.

Informally, one can view (2) as the assertion that typically has size

.

The first moment method also shows that

and so we can normalise out the means using the identity

Replacing the by

(and

by

) we may thus assume for simplicity that all the

have mean zero.

Now we consider what the second moment method gives us. We square and take expectations to obtain

If we assume that the are pairwise independent (in addition to having mean zero), then

vanishes unless

, in which case this expectation is equal to

. We thus have

which when combined with Chebyshev’s inequality (and the mean zero normalisation) yields the large deviation inequality

Without the normalisation that the have mean zero, we obtain

Informally, this is the assertion that typically has size

, if we have pairwise independence. Note also that we do not need the full strength of the pairwise independence assumption; the slightly weaker hypothesis of being pairwise uncorrelated would have sufficed.

The inequality (5) is sharp in two ways. Firstly, we cannot expect any significant concentration in any range narrower than the standard deviation , as this would likely contradict (3). Secondly, the quadratic-type decay in

in (5) is sharp given the pairwise independence hypothesis. For instance, suppose that

, and that

, where

is drawn uniformly at random from the cube

, and

are an enumeration of the non-zero elements of

. Then a little Fourier analysis shows that each

for

has mean zero, variance

, and are pairwise independent in

; but

is equal to

, which is equal to

with probability

; this is despite the standard deviation of

being just

. This shows that (5) is essentially (i.e. up to constants) sharp here when

.

Now we turn to higher moments. Let us assume that the are normalised to have mean zero and variance at most

, and are also almost surely bounded in magnitude by some

:

. (The interesting regime here is when

, otherwise the variance is in fact strictly smaller than

.) To simplify the exposition very slightly we will assume that the

are real-valued; the complex-valued case is very analogous (and can also be deduced from the real-valued case) and is left to the reader.

Let us also assume that the are

-wise independent for some even positive integer

. With this assumption, we can now estimate the

moment

To compute the expectation of the product, we can use the -wise independence, but we need to divide into cases (analogous to the

and

cases in the second moment calculation above) depending on how various indices are repeated. If one of the

only appear once, then the entire expectation is zero (since

has mean zero), so we may assume that each of the

appear at least twice. In particular, there are at most

distinct

which appear. If exactly

such terms appear, then from the unit variance assumption we see that the expectation has magnitude at most

; more generally, if

terms appear, then from the unit variance assumption and the upper bound by

we see that the expectation has magnitude at most

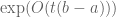

. This leads to the upper bound

where is the number of ways one can assign integers

in

such that each

appears at least twice, and such that exactly

integers appear.

We are now faced with the purely combinatorial problem of estimating . We will use a somewhat crude bound. There are

ways to choose

integers from

. Each of the integers

has to come from one of these

integers, leading to the crude bound

which after using a crude form of Stirling’s formula gives

and so

If we make the mild assumption

then from the geometric series formula we conclude that

(say), which leads to the large deviation inequality

This should be compared with (2), (5). As increases, the rate of decay in the

parameter improves, but to compensate for this, the range that

concentrates in grows slowly, to

rather than

.

Remark 1 Note how it was important here that

was even. Odd moments, such as

, can be estimated, but due to the lack of the absolute value sign, these moments do not give much usable control on the distribution of the

. One could be more careful in the combinatorial counting than was done here, but the net effect of such care is only to improve the unspecified constant

(which can easily be made explicit, but we will not do so here).

Now suppose that the are not just

-wise independent for any fixed

, but are in fact jointly independent. Then we can apply (7) for any

obeying (6). We can optimise in

by setting

to be a small multiple of

, and conclude the gaussian-type bound

for some absolute constants , provided that

for some small

. (Note that the bound (8) is trivial for

, so we may assume that

is small compared to this quantity.) Thus we see that while control of each individual moment

only gives polynomial decay in

, by using all the moments simultaneously one can obtain square-exponential decay (i.e. subgaussian type decay).

By using Stirling’s formula (Exercise 2 from Notes 0a) one can show that the quadratic decay in (8) cannot be improved; see Exercise 2 below.

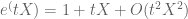

It was a little complicated to manage such large moments . A slicker way to proceed (but one which exploits the joint independence and commutativity more strongly) is to work instead with the exponential moments

, which can be viewed as a sort of generating function for the power moments. A useful lemma in this regard is

Lemma 1 (Hoeffding’s lemma) Let

be a scalar variable taking values in an interval

. Then for any

,

Proof: It suffices to prove the first inequality, as the second then follows using the bound and from various elementary estimates.

By subtracting the mean from we may normalise

. By dividing

(and multiplying

to balance) we may assume that

, which implies that

. We then have the Taylor expansion

which on taking expectations gives

and the claim follows.

Exercise 1 Show that the

factor in (10) can be replaced with

, and that this is sharp. (Hint: use Jensen’s inequality.)

We now have the fundamental Chernoff bound:

Theorem 2 (Chernoff inequality) Let

be independent scalar random variables with

almost surely, with mean

and variance

. Then for any

, one has

for some absolute constants

, where

and

.

Proof: By taking real and imaginary parts we may assume that the are real. By subtracting off the mean (and adjusting

appropriately) we may assume that

(and so

); dividing the

(and

) through by

we may assume that

. By symmetry it then suffices to establish the upper tail estimate

(with slightly different constants ).

To do this, we shall first compute the exponential moments

where is a real parameter to be optimised later. Expanding out the exponential and using the independence hypothesis, we conclude that

To compute , we use the hypothesis that

and (9) to obtain

Thus we have

and thus by Markov’s inequality

If we optimise this in , subject to the constraint

, we obtain the claim.

Informally, the Chernoff inequality asserts that is sharply concentrated in the range

. The bounds here are fairly sharp, at least when

is not too large:

Exercise 2 Let

be fixed independently of

, and let

be iid copies of a Bernoulli random variable that equals

with probability

, thus

and

, and so

and

. Using Stirling’s formula (Notes 0a), show that

for some absolute constants

and all

. What happens when

is much larger than

?

Exercise 3 Show that the term

in (11) can be replaced with

(which is superior when

). (Hint: Allow

to exceed

.) Compare this with the results of Exercise 2.

Exercise 4 (Hoeffding’s inequality) Let

be independent real variables, with

taking values in an interval

, and let

. Show that one has

for some absolute constants

, where

.

Remark 2 As we can see, the exponential moment method is very slick compared to the power moment method. Unfortunately, due to its reliance on the identity

, this method relies very strongly on commutativity of the underlying variables, and as such will not be as useful when dealing with noncommutative random variables, and in particular with random matrices. Nevertheless, we will still be able to apply the Chernoff bound to good effect to various components of random matrices, such as rows or columns of such matrices.

The full assumption of joint independence is not completely necessary for Chernoff-type bounds to be present. It suffices to have a martingale difference sequence, in which each can depend on the preceding variables

, but which always has mean zero even when the preceding variables are conditioned out. More precisely, we have Azuma’s inequality:

Theorem 3 (Azuma’s inequality) Let

be a sequence of scalar random variables with

almost surely. Assume also that we have the martingale difference property

almost surely for all

(here we assume the existence of a suitable disintegration in order to define the conditional expectation, though in fact it is possible to state and prove Azuma’s inequality without this disintegration). Then for any

, the sum

obeys the large deviation inequality

for some absolute constants

.

A typical example of here is a dependent random walk, in which the magnitude and probabilities of the

step are allowed to depend on the outcome of the preceding

steps, but where the mean of each step is always fixed to be zero.

Proof: Again, we can reduce to the case when the are real, and it suffices to establish the upper tail estimate

Note that almost surely, so we may assume without loss of generality that

.

Once again, we consider the exponential moment for some parameter

. We write

, so that

We do not have independence between and

, so cannot split the expectation as in the proof of Chernoff’s inequality. Nevertheless we can use conditional expectation as a substitute. We can rewrite the above expression as

The quantity is deterministic once we condition on

, and so we can pull it out of the conditional expectation:

Applying (10) to the conditional expectation, we have

and

Iterating this argument gives

and thus by Markov’s inequality

Optimising in gives the claim.

Exercise 5 Suppose we replace the hypothesis

in Azuma’s inequality with the more general hypothesis

for some scalars

. Show that we still have (13), but with

replaced by

.

Remark 3 The exponential moment method is also used frequently in harmonic analysis to deal with lacunary exponential sums, or sums involving Radamacher functions (which are the analogue of lacunary exponential sums for characteristic

). Examples here include Khintchine’s inequality (and the closely related Kahane’s inequality). The exponential moment method also combines very well with log-Sobolev inequalities, as we shall see below (basically because the logarithm inverts the exponential), as well as with the closely related hypercontractivity inequalities.

— 2. The truncation method —

To summarise the discussion so far, we have identified a number of large deviation inequalities to control a sum :

- The zeroth moment method bound (1), which requires no moment assumptions on the

but is only useful when

is usually zero, and has no decay in

.

- The first moment method bound (2), which only requires absolute integrability on the

, but has only a linear decay in

.

- The second moment method bound (5), which requires second moment and pairwise independence bounds on

, and gives a quadratic decay in

.

- Higher moment bounds (7), which require boundedness and

-wise independence, and give a

power decay in

(or quadratic-exponential decay, after optimising in

).

- Exponential moment bounds such as (11) or (13), which require boundedness and joint independence (or martingale behaviour), and give quadratic-exponential decay in

.

We thus see that the bounds with the strongest decay in require strong boundedness and independence hypotheses. However, one can often partially extend these strong results from the case of bounded random variables to that of unbounded random variables (provided one still has sufficient control on the decay of these variables) by a simple but fundamental trick, known as the truncation method. The basic idea here is to take each random variable

and split it as

, where

is a truncation parameter to be optimised later (possibly in manner depending on

),

is the restriction of to the event that

(thus

vanishes when

is too large), and

is the complementary event. One can similarly split where

and

The idea is then to estimate the tail of and

by two different means. With

, the point is that the variables

have been made bounded by fiat, and so the more powerful large deviation inequalities can now be put into play. With

, in contrast, the underlying variables

are certainly not bounded, but they tend to have small zeroth and first moments, and so the bounds based on those moment methods tend to be powerful here. (Readers who are familiar with harmonic analysis may recognise this type of divide and conquer argument as an interpolation argument.)

Let us begin with a simple application of this method.

Theorem 4 (Weak law of large numbers) Let

be iid scalar random variables with

for all

, where

is absolutely integrable. Then

converges in probability to

.

Proof: By subtracting from

we may assume without loss of generality that

has mean zero. Our task is then to show that

for all fixed

.

If has finite variance, then the claim follows from (5). If

has infinite variance, we cannot apply (5) directly, but we may perform the truncation method as follows. Let

be a large parameter to be chosen later, and split

,

(and

) as discussed above. The variable

is bounded and thus has bounded variance; also, from the dominated convergence theorem we see that

(say) if

is large enough. From (5) we conclude that

(where the rate of decay here depends on and

). Meanwhile, to deal with the tail

we use (2) to conclude that

But by the dominated convergence theorem (or monotone convergence theorem), we may make as small as we please (say, smaller than

) by taking

large enough. Summing, we conclude that

since is arbitrary, we obtain the claim.

A more sophisticated variant of this argument (which I gave in this earlier blog post, which also has some further discussion and details) gives

Theorem 5 (Strong law of large numbers) Let

be iid scalar random variables with

for all

, where

is absolutely integrable. Then

converges almost surely to

.

Proof: We may assume without loss of generality that is real, since the complex case then follows by splitting into real and imaginary parts. By splitting

into positive and negative parts, we may furthermore assume that

is non-negative. (Of course, by doing so, we can no longer normalise

to have mean zero, but for us the non-negativity will be more convenient than the zero mean property.) In particular,

is now non-decreasing in

.

Next, we apply a sparsification trick. Let . Suppose that we knew that, almost surely,

converged to

for

of the form

for some integer

. Then, for all other values of

, we see that asymptotically,

can only fluctuate by a multiplicative factor of

, thanks to the monotone nature of

. Because of this and countable additivity, we see that it suffices to show that

converges to

. Actually, it will be enough to show that almost surely, one has

for all but finitely many

.

Fix . As before, we split

and

, but with the twist that we now allow

to depend on

. Then for

large enough we have

(say), by dominated convergence. Applying (5) as before, we see that

for some depending only on

(the exact value is not important here). To handle the tail, we will not use the first moment bound (2) as done previously, but now turn to the zeroth-moment bound (1) to obtain

summing, we conclude

Applying the Borel-Cantelli lemma (Exercise 1 from Notes 0), we see that we will be done as long as we can choose such that

and

are both finite. But this can be accomplished by setting and interchanging the sum and expectations (writing

as

) and using the lacunary nature of the

.

To give another illustration of the truncation method, we extend a version of the Chernoff bound to the subgaussian case.

Proposition 6 Let

be iid copies of a subgaussian random variable

, thus

obeys a bound of the form

for all

and some

. Let

. Then for any sufficiently large

(independent of

) we have

for some constants

depending on

. Furthermore,

grows linearly in

as

.

Proof: By subtracting the mean from we may normalise

. We perform a dyadic decomposition

where and

. We similarly split

where . Then by the union bound and the pigeonhole principle we have

(say). Each is clearly bounded in magnitude by

; from the subgaussian hypothesis one can also verify that the mean and variance of

are at most

for some

. If

is large enough, an application of the Chernoff bound (11) (or more precisely, the refinement in Exercise 3) then gives (after some computation)

(say) for some , and the claim follows.

Exercise 6 Show that the hypothesis that

is sufficiently large can be replaced by the hypothesis that

is independent of

. Hint: There are several approaches available. One can adapt the above proof; one can modify the proof of the Chernoff inequality directly; or one can figure out a way to deduce the small

case from the large

case.

Exercise 7 Show that the subgaussian hypothesis can be generalised to a sub-exponential tail hypothesis

provided that

. Show that the result also extends to the case

, except with the exponent

replaced by

for some

. (I do not know if the

loss can be removed, but it is easy to see that one cannot hope to do much better than this, just by considering the probability that

(say) is already as large as

.)

— 3. Lipschitz combinations —

In the preceding discussion, we had only considered the linear combination of independent variables

. Now we consider more general combinations

, where we write

for short. Of course, to get any non-trivial results we must make some regularity hypotheses on

. It turns out that a particularly useful class of regularity hypothesis here is a Lipschitz hypothesis – that small variations in

lead to small variations in

. A simple example of this is McDiarmid’s inequality:

Theorem 7 (McDiarmid’s inequality) Let

be independent random variables taking values in ranges

, and let

be a function with the property that if one freezes all but the

coordinate of

for some

, then

only fluctuates by most

, thus

for all

,

for

. Then for any

, one has

for some absolute constants

, where

.

Proof: We may assume that is real. By symmetry, it suffices to show the one-sided estimate

To compute this quantity, we again use the exponential moment method. Let be a parameter to be chosen later, and consider the exponential moment

To compute this, let us condition to be fixed, and look at the conditional expectation

We can simplify this as

where

For fixed,

only fluctuates by at most

and has mean zero. Applying (10), we conclude that

Integrating out the conditioning, we see that we have upper bounded (16) by

We observe that is a function

of

, where

obeys the same hypotheses as

(but for

instead of

). We can then iterate the above computation

times and eventually upper bound (16) by

which we rearrange as

and thus by Markov’s inequality

Optimising in then gives the claim.

Exercise 8 Show that McDiarmid’s inequality implies Hoeffding’s inequality (Exercise 4).

Remark 4 One can view McDiarmid’s inequality as a tensorisation of Hoeffding’s lemma, as it leverages the latter lemma for a single random variable to establish an analogous result for

random variables. It is possible to apply this tensorisation trick to random variables taking values in more sophisticated metric spaces than an interval

, leading to a class of concentration of measure inequalities known as transportation cost-information inequalities, which will not be discussed here.

The most powerful concentration of measure results, though, do not just exploit Lipschitz type behaviour in each individual variable, but joint Lipschitz behaviour. Let us first give a classical instance of this, in the special case when the are gaussian variables. A key property of gaussian variables is that any linear combination of independent gaussians is again an independent gaussian:

Exercise 9 Let

be independent real gaussian variables with

, and let

be real constants. Show that

is a real gaussian with mean

and variance

.

Show that the same claims also hold with complex gaussians and complex constants

.

Exercise 10 (Rotation invariance) Let

be an

-valued random variable, where

are iid real gaussians. Show that for any orthogonal matrix

,

.

Show that the same claim holds for complex gaussians (so

is now

-valued), and with the orthogonal group

replaced by the unitary group

.

Theorem 8 (Gaussian concentration inequality for Lipschitz functions) Let

be iid real gaussian variables, and let

be a

-Lipschitz function (i.e.

for all

, where we use the Euclidean metric on

). Then for any

one has

for some absolute constants

.

Proof: We use the following elegant argument of Maurey and Pisier. By subtracting a constant from , we may normalise

. By symmetry it then suffices to show the upper tail estimate

By smoothing slightly we may assume that

is smooth, since the general case then follows from a limiting argument. In particular, the Lipschitz bound on

now implies the gradient estimate

for all .

Once again, we use the exponential moment method. It will suffice to show that

for some constant and all

, as the claim follows from Markov’s inequality and optimisation in

as in previous arguments.

To exploit the Lipschitz nature of , we will need to introduce a second copy of

. Let

be an independent copy of

. Since

, we see from Jensen’s inequality that

and thus (by independence of and

)

It is tempting to use the fundamental theorem of calculus along a line segment,

to estimate , but it turns out for technical reasons to be better to use a circular arc instead,

The reason for this is that is another gaussian random variable equivalent to

, as is its derivative

(by Exercise 9); furthermore, and crucially, these two random variables are independent (by Exercise 10).

To exploit this, we first use Jensen’s inequality to bound

Applying the chain rule and taking expectations, we have

Let us condition to be fixed, then

; applying Exercise 9 and (17), we conclude that

is normally distributed with standard deviation at most

. As such we have

for some absolute constant ; integrating out the conditioning on

we obtain the claim.

Exercise 11 Show that Theorem 8 is equivalent to the inequality

holding for all

and all measurable sets

, where

is an

-valued random variable with iid gaussian components

, and

is the

-neighbourhood of

.

Now we give a powerful concentration inequality of Talagrand, which we will rely heavily on later in this course.

Theorem 9 (Talagrand concentration inequality) Let

, and let

be independent complex variables with

for all

. Let

be a

-Lipschitz convex function (where we identify

with

for the purposes of defining “Lipschitz” and “convex”). Then for any

one has

for some absolute constants

, where

is a median of

.

We now prove the theorem, following the remarkable argument of Talagrand.

By dividing through by we may normalise

.

now takes values in the convex set

, where

is the unit disk in

. It will suffice to establish the inequality

for any convex set in

and some absolute constant

, where

is the Euclidean distance between

and

. Indeed, if one obtains this estimate, then one has

for any (as can be seen by applying (20) to the convex set

). Applying this inequality of one of

equal to the median

of

yields (18), which in turn implies that

which then gives (19).

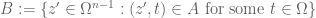

We would like to establish (20) by induction on dimension . In the case when

are Bernoulli variables, this can be done; see this previous blog post. In the general case, it turns out that in order to close the induction properly, one must strengthen (20) by replacing the Euclidean distance

by an essentially larger quantity, which I will call the combinatorial distance

from

to

. For each vector

and

, we say that

supports

if

is non-zero only when

is non-zero. Define the combinatorial support

of

relative to

to be all the vectors in

that support at least one vector in

. Define the combinatorial hull

of

relative to

to be the convex hull of

, and then define the combinatorial distance

to be the distance between

and the origin.

Lemma 10 (Combinatorial distance controls Euclidean distance) Let

be a convex subset of

.

.

Proof: Suppose . Then there exists a convex combination

of elements

which has magnitude at most

. For each such

, we can find a vector

supported by

. As

both lie in

, every coefficient of

has magnitude at most

, and is thus bounded in magnitude by twice the corresponding coefficent of

. If we then let

be the convex combination of the

indicated by

, then the magnitude of each coefficient of

is bounded by twice the corresponding coefficient of

, and so

. On the other hand, as

is convex,

lies in

, and so

. The claim follows.

Thus to show (20) it suffices (after a modification of the constant ) to show that

We first verify the one-dimensional case. In this case, equals

when

, and

otherwise, and the claim follows from elementary calculus (for

small enough).

Now suppose that and the claim has already been proven for

. We write

, and let

be a slice of

. We also let

. We have the following basic inequality:

Lemma 11 For any

, we have

Proof: Observe that contains both

and

, and so by convexity,

contains one of

or

whenever

and

. The claim then follows from Pythagoras’ theorem and the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality.

Let us now freeze and consider the conditional expectation

Using the above lemma (with some depending on

to be chosen later), we may bound the left-hand side of (21) by

applying Hölder’s inequality and the induction hypothesis (21), we can bound this by

which we can rearrange as

where (here we note that the event

is independent of

). Note that

. We then apply the elementary inequality

which can be verified by elementary calculus if is small enough (in fact one can take

). We conclude that

Taking expectations in we conclude that

Using the inequality with

we conclude (21) as desired.

The above argument was elementary, but rather “magical” in nature. Let us now give a somewhat different argument of Ledoux, based on log-Sobolev inequalities, which gives the upper tail bound

but curiously does not give the lower tail bound. (The situation is not symmetric, due to the convexity hypothesis on .)

Once again we can normalise . By regularising

we may assume that

is smooth. The first step is to establish the following log-Sobolev inequality:

Lemma 12 (Log-Sobolev inequality) Let

be a smooth convex function. Then

for some absolute constant

(independent of

).

Remark 5 If one sets

and normalises

, this inequality becomes

which more closely resembles the classical log-Sobolev inequality of Gross. The constant

here can in fact be taken to be

; see Ledoux’s paper.

Proof: We first establish the -dimensional case. If we let

be an independent copy of

, observe that the left-hand side can be rewritten as

From Jensen’s inequality, , so it will suffice to show that

From convexity of (and hence of

) and the bounded nature of

, we have

and

when , which leads to

in this case. Similarly when (swapping

and

). The claim follows.

To show the general case, we induct on (keeping care to ensure that the constant

does not change in this induction process). Write

, where

. From induction hypothesis, we have

where is the

-dimensional gradient and

. Taking expectations, we conclude that

From the convexity of and Hölder’s inequality we see that

is also convex, and

. By the

case already established, we have

Now, by the chain rule

where is the derivative of

in the

direction. Applying Cauchy-Schwarz, we conclude

Inserting this into (23), (24) we close the induction.

Now let be convex and

-Lipschitz. Applying the above lemma to

for any

, we conclude that

setting , we can rewrite this as a differential inequality

which we can rewrite as

From Taylor expansion we see that

as , and thus

for any . In other words,

By Markov’s inequality, we conclude that

optimising in gives (22).

Remark 6 The same argument, starting with Gross’s log-Sobolev inequality for the gaussian measure, gives the upper tail component of Theorem 8, with no convexity hypothesis on

. The situation is now symmetric with respect to reflections

, and so one obtains the lower tail component as well. The method of obtaining concentration inequalities from log-Sobolev inequalities (or related inequalities, such as Poincaré-type ienqualities) by combining the latter with the exponential moment method is known as Herbst’s argument, and can be used to establish a number of other functional inequalities of interest.

We now close with a simple corollary of the Talagrand concentration inequality, which will be extremely useful in the sequel.

Corollary 13 (Distance between random vector and a subspace) Let

be independent complex-valued random variables with mean zero and variance

, and bounded almost surely in magnitude by

. Let

be a subspace of

of dimension

. Then for any

, one has

for some absolute constants

.

Informally, this corollary asserts that the distance between a random vector and an arbitrary subspace

is typically equal to

.

Proof: The function is convex and

-Lipschitz. From Theorem 9, one has

To finish the argument, it then suffices to show that

We begin with a second moment calculation. Observe that

where is the orthogonal projection matrix to the complement

of

, and

are the components of

. Taking expectations, we obtain

where the latter follows by representing in terms of an orthonormal basis of

. This is close to what we need, but to finish the task we need to obtain some concentration of

around its mean. For this, we write

where is the Kronecker delta. The summands here are pairwise uncorrelated for

, and the

cases can be combined with the

cases by symmetry. Each summand also has a variance of

. We thus have the variance bound

where the latter bound comes from representing in terms of an orthonormal basis of

. From this, (25), and Chebyshev’s inequality, we see that the median of

is equal to

, which implies on taking square roots that the median of

is

, as desired.

127 comments

Comments feed for this article

14 November, 2013 at 10:57 pm

Anonymous

Are the summands for last applicational result really independent or merely uncorrelated?

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

24 October, 2014 at 12:26 am

Anonymous

Do you want the variance to be “at least 1” or “at most 1”. The current formulation seems inconsistent with the note right after this line.

[“At most”. Note clarified to remove the confusion. -T.]

20 September, 2015 at 10:11 am

Entropy and rare events | What's new

[…] inequality, but there are of course many other estimates of this type (see e.g. this previous blog post for some others). Roughly speaking, concentration of measure inequalities allow one to make […]

21 September, 2015 at 1:22 pm

Jiasen Yang

Dear Professor Tao,

Thank you for the detailed post! I’ve been going through the proof of McDiarmid’s inequality, and I don’t see why it is necessary to assume that the ‘s are independent. I wonder if you could point out which step(s) I missed?

‘s are independent. I wonder if you could point out which step(s) I missed?

Thanks very much!

[One needs the independence to ensure that (say) continues to have mean zero even after conditioning on

continues to have mean zero even after conditioning on  . -T. Note also that the theorem fails quite badly if for instance one has the very strong coupling

. -T. Note also that the theorem fails quite badly if for instance one has the very strong coupling  . -T.]

. -T.]

21 September, 2015 at 7:23 pm

Jiasen Yang

Dear Professor Tao,

Thank you for your timely reply! Your coupling argument certainly makes sense, but I’m still having trouble determining which step of the proof uses independence directly. Following your point, I agree that $E[X_n] \neq E[X_n|X_1,\ldots,X_{n-1}]$ in general, but I don’t see where $X_n$ is assumed to have mean zero?

Actually, my question originally arose as I was reading a paper which claims to use McDiarmid’s inequality for dependent $X_i$’s after replacing the assumption

$$ |F(x_1,\ldots,x_{i-1},x_i,x_{i+1},\ldots,x_n) – F(x_1,\ldots,x_{i-1},x_i’,x_{i+1},\ldots,x_n)| \leq c_i $$

by

$$ |\bf{E}[f(X)|x_1,\ldots, x_{i-1},x_i] – \bf{E}[f(X)|x_1,\ldots, x_{i-1},x_i’]| \le c_i $$, but I don’t see why this new assumption resolves the issue.

Thank you again, and please forgive me for my stubbornness!

21 September, 2015 at 7:39 pm

Terence Tao

Sorry, my previous reply was quite incorrect, I was thinking of a different concentration equality. For McDiarmid, the claim that the conditioned function obeys the same hypotheses as the original function

obeys the same hypotheses as the original function  requires the independence hypothesis, as one will find if one expands out the proof of this claim.

requires the independence hypothesis, as one will find if one expands out the proof of this claim.

21 September, 2015 at 8:08 pm

Jiasen Yang

Ah! I finally see your point. Thank you Professor!

23 October, 2015 at 8:06 am

275A, Notes 3: The weak and strong law of large numbers | What's new

[…] theory and high dimensional geometry. We will not discuss these topics much in this course, but see this previous blog post for some further […]

6 November, 2015 at 4:19 pm

Mahmood

Dear Professor Tao,

In the proof of Lemma 11 and the definition of set . What happens if such

. What happens if such  is equal to

is equal to  ? Is it still valid to say that

? Is it still valid to say that  . For example, when the set

. For example, when the set  has the points whose

has the points whose  coordinates are all equal to

coordinates are all equal to  , then

, then  does not have any element with the last coordinate 1. Am I missing something?

does not have any element with the last coordinate 1. Am I missing something?

Thanks.

6 November, 2015 at 9:46 pm

Terence Tao

Oops, you’re right, the case has to be handled separately, but the bound is better in that case (one can stay in the

case has to be handled separately, but the bound is better in that case (one can stay in the  slice). I’ve updated the argument accordingly.

slice). I’ve updated the argument accordingly.

7 November, 2015 at 8:51 am

mazrouei

Thanks for your reply.

19 November, 2015 at 2:51 pm

275A, Notes 5: Variants of the central limit theorem | What's new

[…] in which the underlying random variable is not bounded, but enjoys good moment bounds. See this previous blog post for these inequalities and some further discussion. Last, but certainly not least, there is an […]

17 February, 2016 at 6:59 pm

Anonymous

Hello Professor Tao,

In the proof of SLLN, I am not sure what do you mean by ‘countable additivity’ in building the connections bewteen convergence of two sequences. Does it mean adding O(\varepsilon)?

Thanks!

Jack

17 February, 2016 at 7:22 pm

Terence Tao

If is almost surely convergent to

is almost surely convergent to  , then almost surely it is the case that

, then almost surely it is the case that  fluctuates by at most

fluctuates by at most  around

around  (in the sense that the limit superior and limit inferior are both almost surely

(in the sense that the limit superior and limit inferior are both almost surely  . Setting

. Setting  (say) for

(say) for  and using countable additivity (which implies that the countable intersection of almost sure events is still almost sure, we conclude that the limit superior and limit inferior are both almost surely

and using countable additivity (which implies that the countable intersection of almost sure events is still almost sure, we conclude that the limit superior and limit inferior are both almost surely  , giving the SLLN.

, giving the SLLN.

17 February, 2016 at 8:33 pm

Anonymous

Ah, I see. Thanks a lot for your reply!

Best,

Jack

9 April, 2016 at 7:44 am

Anonymous

Dear Prof. Tao, I believe your notes are just impressive.

What can we say on the lower bound on $Pr[|S_n|\geq \lambda]\geq ?$,depending on the moments of the distribution of the jointly independent, zero mean, variables $X_i$?

11 April, 2016 at 8:50 am

Terence Tao

This is the realm of large deviation theory; these bounds tend to depend in various subtle ways on the precise distribution of the independent variables. See for instance this paper of Nagaev for a classical survey of results; probably there are more up to date surveys also.

14 April, 2016 at 10:39 am

gninrepoli

I think that the probability of a recursive nature, so this phenomenon is possible. Probability – it’s just part of the recursion. Any probabilistic model is necessary to approximate recursion, which we can control. For example the set of prime numbers is recursive. But how to prove it.

25 April, 2016 at 3:24 pm

Nathan

Dear Prof. Tao,

First I would like to thank you for your notes, which are quite impressive!

I do not understand why each summand has a variance of in the computation of the variance of

in the computation of the variance of  (corollary 13). Since

(corollary 13). Since  and a term in the computation has the form

and a term in the computation has the form ![E[X_i^2X_j^2]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=E%5BX_i%5E2X_j%5E2%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) , shouldn’t we have an

, shouldn’t we have an  ?

?

Thanks!

26 April, 2016 at 8:34 am

Terence Tao

26 April, 2016 at 11:27 am

Nathan

Thank you!

2 March, 2017 at 12:17 am

keej

I was also stuck on this point; thanks for clarifying!

5 June, 2016 at 4:49 am

Vaibhav

Hi Prof. Terrence Tao,

I am a very simple question. In, (McDiarmid’s inequality) it is not clear how does it depend upon N, the number of random variables concerned. Intuitively, and as you mention elsewhere, the inequality should become stronger. That is, as the number of random variables increase, the deviation from the mean of the function should be less likely. Could you kindly clarify.

Quoting you:

“The basic intuition here is that it is difficult for a large number of independent variables {X_1,\ldots,X_n} to “work together” to simultaneously pull a sum {X_1+\ldots+X_n} or a more general combination {F(X_1,\ldots,X_n)} too far away from its mean. Independence here is the key; concentration of measure results typically fail if the {X_i} are too highly correlated with each other.”

I fail to see this effect.

6 June, 2016 at 1:53 pm

Terence Tao

Let’s say we are working in the normalisation . The hypothesis of Theorem 7 allows

. The hypothesis of Theorem 7 allows  to range over an interval of size

to range over an interval of size  ; but McDiarmid’s inequality shows that concentration instead occurs at a shorter interval at the scale of

; but McDiarmid’s inequality shows that concentration instead occurs at a shorter interval at the scale of  .

.

6 June, 2016 at 6:19 pm

Vaibhav

Dear Prof. Tao, Thanks a lot. This helps most certainly.

6 June, 2016 at 6:51 pm

Vaibhav

Dear Prof. Tao,

I had a following question about Levy’s Lemma (another celebreated concentration of measure result).

First the Levy’s Lemma.

Let $f : S^k \rightarrow R$

be a function with Lipschitz constant $\eta$ (with respect to the Euclidean norm) and $X \in k$

and a point $X \in S^{k}$ be chosen uniformly at random. Then

\begin{align}

\label{levy}

Pr\{|f(X) – \bar{f}| > \alpha\}\le exp (-C(k+1)\alpha^{2}/\eta^2 )

\end{align}

for some constant $C >0$ and $\bar{f}$ is the mean value of the function over the sphere.

Now, here is my question: This Lemma seems to hold for a point chosen

uniformly at random over a sphere.

My question is….suppose I choose a point on an N dimensional sphere (X_1, X_2,…, X_N) such that (X_1^2, X_2^2, …, X_N^2) is chosen from a uniform distribution.

Certainly (X_1^2, X_2^2, …, X_N^2) chosen from a uniform distribution does not imply (X_1, X_2,…, X_N) will be a uniformly random point on the sphere.

But intuitively, I will expect Levy’s Lemma (or say a weaker version) to hold as I expect it to hold

for almost all points on the sphere.

My computer simulations also show this to be the case.

But, I cannot make mathematical arguments to justify my intuition and my simulations.

Best,

vaibhav

Ps: If I can show this, I can show a neat result in evolutionary biology, which I will be happy to show it to you if you would like.

Many thanks to you!

28 June, 2016 at 5:41 am

Ahn

Dear prof. Tao,

While I read the proof of proposition 6, I could not follow the step at the end where you applied chernoff bound. For example, what did you choose for lambda?

I would appreciate your help.

29 June, 2016 at 6:51 am

Terence Tao

There is a lot of latitude here in what to choose for , for instance one can take

, for instance one can take  for some small

for some small  . Note that the bound on the RHS is not optimal, but suffices for the application at hand.

. Note that the bound on the RHS is not optimal, but suffices for the application at hand.

8 November, 2016 at 8:40 am

Fast Randomized SVD – Facebook Research

[…] our approximation by appealing to concentration of measure results for random matrices – see Terry Tao’s lecture notes on the topic for some useful […]

12 February, 2017 at 11:53 am

keej

Could anyone please explain why in the proof of Hoeffding’s lemma, the first Taylor expansion is and not just the naive

and not just the naive  ?

?

12 February, 2017 at 3:39 pm

Anonymous

The simpler estimate for the remainder term applies only for bounded

for the remainder term applies only for bounded  .

.

12 February, 2017 at 5:01 pm

keej

Of course, thank you.

13 May, 2017 at 5:28 pm

Zahra

Hello Prof. Tao,

Any known results for the extension of theorem 8 to the case when be a vector of iid sub-gaussian variables? Many Thanks.

be a vector of iid sub-gaussian variables? Many Thanks.

[Probably. I don’t have references handy, but I would recommend checking Ledoux’s book on the subject. -T.]

22 May, 2017 at 5:55 pm

Quantitative continuity estimates | What's new

[…] is the proof by Maurey and Pisier of the gaussian concentration inequality, given in Theorem 8 of this previous blog post. In a similar vein, if one wishes to compare a scalar random variable of mean zero and variance […]

24 December, 2017 at 1:19 pm

AL Ray

I don’t understand something in the proof of the Lemma 10 why is and not

and not  ?

?

Thanks in advance!

[This is a typo, now fixed – T.]

30 December, 2017 at 10:41 pm

Tim

Dear Prof. Tao,

Thanks for the insightful notes. I have two questions:

1. When calculating the variance of d(X, V)^2, a term in the computation will be E[X_i^2 X_j^2], which I think should be 1 instead of O(K^2) since X_i and X_j are independent.

2. Are there any more direct ways to calculate / estimate the expectation of d(X, V)?

Thanks in advance!

31 December, 2017 at 10:29 am

Terence Tao

It’s true one can improve the bound on the variance of , but unfortunately this does not significantly improve the concentration bound because of the uncertainty of

, but unfortunately this does not significantly improve the concentration bound because of the uncertainty of  coming from the use of Theorem 9.

coming from the use of Theorem 9.

I don’t know of much sharper ways to control the expectation, but there are several routes to the concentration property at least, starting with the classic work of Hanson and Wright.

12 November, 2019 at 6:47 pm

254A, Notes 9 – second moment and entropy methods | What's new

[…] random variable will concentrate around its mean if its variance is not too large. See these previous notes for more discussion of the concentration of measure phenomenon. One can often obtain stronger […]

12 November, 2019 at 6:47 pm

254A, Notes 9 – second moment and entropy methods | What's new

[…] random variable will concentrate around its mean if its variance is not too large. See these previous notes for more discussion of the concentration of measure phenomenon. One can often obtain stronger […]

27 June, 2020 at 8:43 pm

Yijia Liu

I have been trying to work out the computations for the final part of proposition 6 but I couldnt get the 2^-m factor.

From https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/3734229/chernoff-bound-for-sum-of-sub-gaussian-variables-via-truncation-method it seems that we cannot replace $1/100(m+1)^2$ with $2^{-m-1}$. Is this a typo or have I missed something in calculations.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

11 October, 2021 at 9:19 am

254A, Supplement 4: Probabilistic models and heuristics for the primes (optional) | What's new

[…] above claim using concentration of measure results such as the Chernoff inequality, as discussed in this previous blog post. The estimate (2) reflects the general heuristic of expected square root cancellation: when summing […]

6 November, 2021 at 10:49 am

Alan Chang

In the proof of Theorem 8, should (all five instances of) be

be  ?

?

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

7 April, 2022 at 6:42 am

Matteo Russo

Dear Prof.Tao,

Upon thanking you for the notes, I would like to ask whether Talagrand’s Inequality held even in the case where 1-Lipschitz is with respect to the l1-norm. If not, what type of concentration guarantees could still be claimed?

Thanks in advance!

7 April, 2022 at 11:17 am

Terence Tao

The standard concentration inequality that is used in such settings is McDiarmid’s inequality.

18 May, 2023 at 9:39 pm

David Roberts

I suspect there’s a (minor) typo in the proof of the Chernoff inequality (Theorem 2). After “we use the hypothesis that and (9) to obtain” there’s an equation, following from the previous display which is an inequality.

and (9) to obtain” there’s an equation, following from the previous display which is an inequality.

And on the conclusion of the proof of that theorem, I suspect that the of the two exponentials comes from an asymmetry in the tails. At least, This is the case in a proof of a special case (sums of arbitrary Bernoulli RVs) I’ve seen in one treatment elsewhere. But I’ve not seen other proofs give an upper bound of this form, in my limit searching.

of the two exponentials comes from an asymmetry in the tails. At least, This is the case in a proof of a special case (sums of arbitrary Bernoulli RVs) I’ve seen in one treatment elsewhere. But I’ve not seen other proofs give an upper bound of this form, in my limit searching.

One thing which I haven’t been able to justify to myself is why you consider the parameter in that proof to be bounded above by 1. Is it somehow due to implicitly needing to consider something like keeping a factor of

in that proof to be bounded above by 1. Is it somehow due to implicitly needing to consider something like keeping a factor of  positive, while at the same time keeping

positive, while at the same time keeping  positive, to use in a previous estimate?

positive, to use in a previous estimate?

19 May, 2023 at 12:32 am

David Roberts

Sorry, one more thought: might the bound on come from needing

come from needing  to still be bounded by 1? Just casting about at this point.

to still be bounded by 1? Just casting about at this point.

20 May, 2023 at 1:34 pm

Terence Tao

Typo now corrected. The condition is needed to be able to estimate the

is needed to be able to estimate the  term in (9) by

term in (9) by  , which allows one to bound the entire RHS of (9) by

, which allows one to bound the entire RHS of (9) by  .

.

20 May, 2023 at 3:32 pm

David Roberts

Oh, excellent, thanks.