Let be iid copies of an absolutely integrable real scalar random variable

, and form the partial sums

. As we saw in the last set of notes, the law of large numbers ensures that the empirical averages

converge (both in probability and almost surely) to a deterministic limit, namely the mean

of the reference variable

. Furthermore, under some additional moment hypotheses on the underlying variable

, we can obtain square root cancellation for the fluctuation

of the empirical average from the mean. To simplify the calculations, let us first restrict to the case

of mean zero and variance one, thus

and

Then, as computed in previous notes, the normalised fluctuation also has mean zero and variance one:

This and Chebyshev’s inequality already indicates that the “typical” size of is

, thus for instance

goes to zero in probability for any

that goes to infinity as

. If we also have a finite fourth moment

, then the calculations of the previous notes also give a fourth moment estimate

From this and the Paley-Zygmund inequality (Exercise 44 of Notes 1) we also get some lower bound for of the form

for some absolute constant and for

sufficiently large; this indicates in particular that

does not converge in any reasonable sense to something finite for any

that goes to infinity.

The question remains as to what happens to the ratio itself, without multiplying or dividing by any factor

. A first guess would be that these ratios converge in probability or almost surely, but this is unfortunately not the case:

Proposition 1 Let

be iid copies of an absolutely integrable real scalar random variable

with mean zero, variance one, and finite fourth moment, and write

. Then the random variables

do not converge in probability or almost surely to any limit, and neither does any subsequence of these random variables.

Proof: Suppose for contradiction that some sequence converged in probability or almost surely to a limit

. By passing to a further subsequence we may assume that the convergence is in the almost sure sense. Since all of the

have mean zero, variance one, and bounded fourth moment, Theorem 25 of Notes 1 implies that the limit

also has mean zero and variance one. On the other hand,

is a tail random variable and is thus almost surely constant by the Kolmogorov zero-one law from Notes 3. Since constants have variance zero, we obtain the required contradiction.

Nevertheless there is an important limit for the ratio , which requires one to replace the notions of convergence in probability or almost sure convergence by the weaker concept of convergence in distribution.

Definition 2 (Vague convergence and convergence in distribution) Let

be a locally compact Hausdorff topological space with the Borel

-algebra. A sequence of finite measures

on

is said to converge vaguely to another finite measure

if one has

as

for all continuous compactly supported functions

. (Vague convergence is also known as weak convergence, although strictly speaking the terminology weak-* convergence would be more accurate.) A sequence of random variables

taking values in

is said to converge in distribution (or converge weakly or converge in law) to another random variable

if the distributions

converge vaguely to the distribution

, or equivalently if

as

for all continuous compactly supported functions

.

One could in principle try to extend this definition beyond the locally compact Hausdorff setting, but certain pathologies can occur when doing so (e.g. failure of the Riesz representation theorem), and we will never need to consider vague convergence in spaces that are not locally compact Hausdorff, so we restrict to this setting for simplicity.

Note that the notion of convergence in distribution depends only on the distribution of the random variables involved. One consequence of this is that convergence in distribution does not produce unique limits: if converges in distribution to

, and

has the same distribution as

, then

also converges in distribution to

. However, limits are unique up to equivalence in distribution (this is a consequence of the Riesz representation theorem, discussed for instance in this blog post). As a consequence of the insensitivity of convergence in distribution to equivalence in distribution, we may also legitimately talk about convergence of distribution of a sequence of random variables

to another random variable

even when all the random variables

and

involved are being modeled by different probability spaces (e.g. each

is modeled by

, and

is modeled by

, with no coupling presumed between these spaces). This is in contrast to the stronger notions of convergence in probability or almost sure convergence, which require all the random variables to be modeled by a common probability space. Also, by an abuse of notation, we can say that a sequence

of random variables converges in distribution to a probability measure

, when

converges vaguely to

. Thus we can talk about a sequence of random variables converging in distribution to a uniform distribution, a gaussian distribution, etc..

From the dominated convergence theorem (available for both convergence in probability and almost sure convergence) we see that convergence in probability or almost sure convergence implies convergence in distribution. The converse is not true, due to the insensitivity of convergence in distribution to equivalence in distribution; for instance, if are iid copies of a non-deterministic scalar random variable

, then the

trivially converge in distribution to

, but will not converge in probability or almost surely (as one can see from the zero-one law). However, there are some partial converses that relate convergence in distribution to convergence in probability; see Exercise 10 below.

Remark 3 The notion of convergence in distribution is somewhat similar to the notion of convergence in the sense of distributions that arises in distribution theory (discussed for instance in this previous blog post), however strictly speaking the two notions of convergence are distinct and should not be confused with each other, despite the very similar names.

The notion of convergence in distribution simplifies in the case of real scalar random variables:

Proposition 4 Let

be a sequence of scalar random variables, and let

be another scalar random variable. Then the following are equivalent:

- (i)

converges in distribution to

.

- (ii)

converges to

for each continuity point

of

(i.e. for all real numbers

at which

is continuous). Here

is the cumulative distribution function of

.

Proof: First suppose that converges in distribution to

, and

is continuous at

. For any

, one can find a

such that

for every . One can also find an

larger than

such that

and

. Thus

and

Let be a continuous function supported on

that equals

on

. Then by the above discussion we have

and hence

for large enough . In particular

A similar argument, replacing with a continuous function supported on

that equals

on

gives

for large enough. Putting the two estimates together gives

for large enough; sending

, we obtain the claim.

Conversely, suppose that converges to

at every continuity point

of

. Let

be a continuous compactly supported function, then it is uniformly continuous. As

is monotone increasing, it can only have countably many points of discontinuity. From these two facts one can find, for any

, a simple function

for some

that are points of continuity of

, and real numbers

, such that

for all

. Thus

Similarly for replaced by

. Subtracting and taking limit superior, we conclude that

and on sending , we obtain that

converges in distribution to

as claimed.

The restriction to continuity points of is necessary. Consider for instance the deterministic random variables

, then

converges almost surely (and hence in distribution) to

, but

does not converge to

.

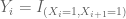

Example 5 For any natural number

, let

be a discrete random variable drawn uniformly from the finite set

, and let

be the continuous random variable drawn uniformly from

. Then

converges in distribution to

. Thus we see that a continuous random variable can emerge as the limit of discrete random variables.

Example 6 For any natural number

, let

be a continuous random variable drawn uniformly from

, then

converges in distribution to the deterministic real number

. Thus we see that discrete (or even deterministic) random variables can emerge as the limit of continuous random variables.

Exercise 7 (Portmanteau theorem) Show that the properties (i) and (ii) in Proposition 4 are also equivalent to the following three statements:

- (iii) One has

for all closed sets

.

- (iv) One has

for all open sets

.

- (v) For any Borel set

whose topological boundary

is such that

, one has

.

(Note: to prove this theorem, you may wish to invoke Urysohn’s lemma. To deduce (iii) from (i), you may wish to start with the case of compact

.)

We can now state the famous central limit theorem:

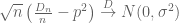

Theorem 8 (Central limit theorem) Let

be iid copies of a scalar random variable

of finite mean

and finite non-zero variance

. Let

. Then the random variables

converges in distribution to a random variable with the standard normal distribution

(that is to say, a random variable with probability density function

). Thus, by abuse of notation

In the normalised case

when

has mean zero and unit variance, this simplifies to

Using Proposition 4 (and the fact that the cumulative distribution function associated to is continuous, the central limit theorem is equivalent to asserting that

as for any

, or equivalently that

Informally, one can think of the central limit theorem as asserting that approximately behaves like it has distribution

for large

, where

is the normal distribution with mean

and variance

, that is to say the distribution with probability density function

. The integrals

can be written in terms of the error function

as

.

The central limit theorem is a basic example of the universality phenomenon in probability – many statistics involving a large system of many independent (or weakly dependent) variables (such as the normalised sums ) end up having a universal asymptotic limit (in this case, the normal distribution), regardless of the precise makeup of the underlying random variable

that comprised that system. Indeed, the universality of the normal distribution is such that it arises in many other contexts than the fluctuation of iid random variables; the central limit theorem is merely the first place in probability theory where it makes a prominent appearance.

We will give several proofs of the central limit theorem in these notes; each of these proofs has their advantages and disadvantages, and can each extend to prove many further results beyond the central limit theorem. We first give Lindeberg’s proof of the central limit theorem, based on exchanging (or swapping) each component of the sum

in turn. This proof gives an accessible explanation as to why there should be a universal limit for the central limit theorem; one then computes directly with gaussians to verify that it is the normal distribution which is the universal limit. Our second proof is the most popular one taught in probability texts, namely the Fourier-analytic proof based around the concept of the characteristic function

of a real random variable

. Thanks to the powerful identities and other results of Fourier analysis, this gives a quite short and direct proof of the central limit theorem, although the arguments may seem rather magical to readers who are not already familiar with Fourier methods. Finally, we give a proof based on the moment method, in the spirit of the arguments in the previous notes; this argument is more combinatorial, but is straightforward and is particularly robust, in particular being well equipped to handle some dependencies between components; we will illustrate this by proving the Erdos-Kac law in number theory by this method. Some further discussion of the central limit theorem (including some further proofs, such as one based on Stein’s method) can be found in this blog post. Some further variants of the central limit theorem, such as local limit theorems, stable laws, and large deviation inequalities, will be discussed in the next (and final) set of notes.

The following exercise illustrates the power of the central limit theorem, by establishing combinatorial estimates which would otherwise require the use of Stirling’s formula to establish.

Exercise 9 (De Moivre-Laplace theorem) Let

be a Bernoulli random variable, taking values in

with

, thus

has mean

and variance

. Let

be iid copies of

, and write

.

- (i) Show that

takes values in

with

. (This is an example of a binomial distribution.)

- (ii) Assume Stirling’s formula

where

is a function of

that goes to zero as

. (A proof of this formula may be found in this previous blog post.) Using this formula, and without using the central limit theorem, show that

as

for any fixed real numbers

.

The above special case of the central limit theorem was first established by de Moivre and Laplace.

We close this section with some basic facts about convergence of distribution that will be useful in the sequel.

Exercise 10 Let

,

be sequences of real random variables, and let

be further real random variables.

- (i) If

is deterministic, show that

converges in distribution to

if and only if

converges in probability to

.

- (ii) Suppose that

is independent of

for each

, and

independent of

. Show that

converges in distribution to

if and only if

converges in distribution to

and

converges in distribution to

. (The shortest way to prove this is by invoking the Stone-Weierstrass theorem, but one can also proceed by proving some version of Proposition 4.) What happens if the independence hypothesis is dropped?

- (iii) If

converges in distribution to

, show that for every

there exists

such that

for all sufficiently large

. (That is to say,

is a tight sequence of random variables.)

- (iv) Show that

converges in distribution to

if and only if, after extending the probability space model if necessary, one can find copies

and

of

and

respectively such that

converges almost surely to

. (Hint: use the Skorohod representation, Exercise 29 of Notes 0.)

- (v) If

converges in distribution to

, and

is continuous, show that

converges in distribution to

. Generalise this claim to the case when

takes values in an arbitrary locally compact Hausdorff space.

- (vi) (Slutsky’s theorem) If

converges in distribution to

, and

converges in probability to a deterministic limit

, show that

converges in distribution to

, and

converges in distribution to

. (Hint: either use (iv), or else use (iii) to control some error terms.) This statement combines particularly well with (i). What happens if

is not assumed to be deterministic?

- (vii) (Fatou lemma) If

is continuous, and

converges in distribution to

, show that

.

- (viii) (Bounded convergence) If

is continuous and bounded, and

converges in distribution to

, show that

.

- (ix) (Dominated convergence) If

converges in distribution to

, and there is an absolutely integrable

such that

almost surely for all

, show that

.

For future reference we also mention (but will not prove) Prokhorov’s theorem that gives a partial converse to part (iii) of the above exercise:

Theorem 11 (Prokhorov’s theorem) Let

be a sequence of real random variables which is tight (that is, for every

there exists

such that

for all sufficiently large

). Then there exists a subsequence

which converges in distribution to some random variable

(which may possibly be modeled by a different probability space model than the

.)

The proof of this theorem relies on the Riesz representation theorem, and is beyond the scope of this course; but see for instance Exercise 29 of this previous blog post. (See also the closely related Helly selection theorem, covered in Exercise 30 of the same post.)

— 1. The Lindeberg approach to the central limit theorem —

We now give the Lindeberg argument establishing the central limit theorem. The proof splits into two unrelated components. The first component is to establish the central limit theorem for a single choice of underlying random variable . The second component is to show that the limiting distribution of

is universal in the sense that it does not depend the choice of underlying random variable. Putting the two components together gives Theorem 8.

We begin with the first component of the argument. One could use the Bernoulli distribution from Exercise 9 as the choice of underlying random variable, but a simpler choice of distribution (in the sense that no appeal to Stirling’s formula is required) is the normal distribution itself. The key computation is:

Lemma 12 (Sum of independent Gaussians) Let

be independent real random variables with normal distributions

,

respectively for some

and

. Then

has the normal distribution

.

This is of course consistent with the additivity of mean and variance for independent random variables, given that random variables with the distribution have mean

and variance

.

Proof: By subtracting and

from

respectively, we may normalise

, by dividing through by

we may also normalise

. Thus

and

for any Borel sets . As

are independent, this implies that

for any Borel set (this follows from the uniqueness of product measure, or equivalently one can use the monotone class lemma starting from the case when

is a finite boolean combination of product sets

). In particular, we have

for any . Making the change of variables

(and using the Fubini-Tonelli theorem as necessary) we can write the right-hand side as

We can complete the square using to write (after some routine algebra)

so on using the identity for any

and

, we can write (2) as

and so has the cumulative distribution function of

, giving the claim.

In the next section we give an alternate proof of the above lemma using the machinery of characteristic functions. A more geometric argument can be given as follows. With the same normalisations as in the above proof, we can write and

for some

. Then we can write

and

where

are iid copies of

. But the joint probability density function

of

is rotation invariant, so

has the same distribution as

, and the claim follows.

From the above lemma we see that if are iid copies of a normal distribution

of mean

and variance

, then

has distribution

, and hence

has distribution exactly equal to

. Thus the central limit theorem is clearly true in this case.

Exercise 13 (Probabilistic interpretation of convolution) Let

be measurable functions with

. Define the convolution

of

and

to be

Show that if

are independent real random variables with probability density functions

respectively, then

has probability density function

.

Now we turn to the general case of the central limit theorem. By subtracting from

(and from each of the

) we may normalise

; by dividing

(and each of the

) by

we may also normalise

. Thus

, and our task is to show that

as , for any continuous compactly supported functions

, where

is a random variable distributed according to

(possibly modeled by a different probability space than the original

). Since any continuous compactly supported function can be approximated uniformly by smooth compactly supported functions (as can be seen from the Weierstrass or Stone-Weierstrass theorems), it suffices to show this for smooth compactly supported

.

Let be iid copies of

; by extending the probability space used to model

(using Proposition 26 from Notes 2), we can model the

and

by a common model, in such a way that the combined collection

of random variables are jointly independent. As we have already proved the central limit theorem in the normally distributed case, we already have

as (indeed we even have equality here). So it suffices to show that

as .

We first establish this claim under the additional simplifying assumption of a finite third moment: . Rather than swap all of the

with all of the

, let us just swap the final

to a

, that is to say let us consider the expression

Writing , we can write this as

To compute this expression we use Taylor expansion. As is smooth and compactly supported, the first three derivatives of

are bounded, leading to the Taylor approximation

where the implied constant depends on . Taking expectations, we conclude that

Now for a key point: as the random variable only depends on

, it is independent of

, and so we can decouple the expectations to obtain

The same considerations apply after swapping with

(which also has a bounded third moment):

But by hypothesis, and

have matching moments to second order:

and

. Thus on subtraction we have

A similar argument (permuting the indices, and replacing some of the with

) gives

for all . Summing the telescoping series, we conclude that

which gives (5). Note how it was important to Taylor expand to at least third order to obtain a total error bound that went to zero, which explains why it is the first two moments of

(or equivalently, the mean and variance) that play such a decisive role in the central limit theorem.

Now we remove the hypothesis of finite third moment. As in the previous set of notes, we use the truncation method, taking advantage of the “room” inherent in the factor in the error term of the above analysis. For technical reasons we have to modify the usual truncation slightly to preserve the mean zero condition. Let

. We split

, where

and

with

; we split

respectively (we are suppressing the dependence of

on

and

to simplify the notation). The random variables

(and

) are chosen to have mean zero, but their variance is not quite one. However, from dominated convergence, the quantity

converges to

, and the variance

converges to

, as

.

Let be iid copies of

. The previous arguments then give

for large enough. We can bound

and thus

for large enough . By Lemma 12,

is distributed as

, and hence

as . We conclude that

Next, we consider the error term

The variable has mean zero, and by dominated convergence, the variance of

goes to zero as

. The above error term is also mean zero and has the same variance as

. In particular, from Cauchy-Schwarz we have

As is smooth and compactly supported, it is Lipschitz continuous, and hence

Taking expectations, and then combining all these estimates, we conclude that

for sufficiently large; letting

go to infinity we obtain (3) as required. This concludes the proof of Theorem 8.

The above argument can be generalised to a central limit theorem for certain triangular arrays, known as the Lindeberg central limit theorem:

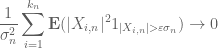

Exercise 14 (Lindeberg central limit theorem) Let

be a sequence of natural numbers going to infinity in

. For each natural number

, let

be jointly independent real random variables of mean zero and finite variance. (We do not require the random variables

to be jointly independent in

, or even to be modeled by a common probability space.) Let

be defined by

and assume that

for all

.

- (i) If one assumes the Lindeberg condition that

as

for any

, then show that the random variables

converge in distribution to a random variable with the normal distribution

.

- (ii) Show that the Lindeberg condition implies the Feller condition

as

.

Note that Theorem 8 (after normalising to the mean zero case ) corresponds to the special case

and

(or, if one wishes,

) of the Lindeberg central limit theorem. It was shown by Feller that if the situation as in the above exercise and the Feller condition holds, then the Lindeberg condition is necessary as well as sufficient for

to converge in distribution to a random variable with normal distribution

; the combined result is sometimes known as the Lindeberg-Feller theorem.

Exercise 15 (Weak Berry-Esséen theorem) Let

be iid copies of a real random variable

of mean zero, unit variance, and finite third moment.

- (i) Show that

whenever

is three times continuously differentiable and compactly supported, with

distributed as

and the implied constant in the

notation absolute.

- (ii) Show that

for any

, with the implied constant absolute.

We will strengthen the conclusion of this theorem in Theorem 37 below.

Remark 16 The Lindeberg exchange method explains why the limiting distribution of statistics such as

depend primarily on the first two moments of the component random variables

, if there is a suitable amount of independence between the

. It turns out that there is an analogous application of the Lindeberg method in random matrix theory, which (very roughly speaking) asserts that appropriate statistics of random matrices such as

depend primarily on the first four moments of the matrix components

, if there is a suitable amount of independence between the

. See for instance this survey article of Van Vu and myself for more discussion of this. The Lindeberg method also suggests that the more moments of

one assumes to match with the Gaussian variable

, the faster the rate of convergence (because one can use higher order Taylor expansions).

We now use the Lindeberg central limit theorem to obtain the converse direction of the Kolmogorov three-series theorem (Exercise 29 of Notes 3).

Exercise 17 (Kolmogorov three-series theorem, converse direction) Let

be a sequence of jointly independent real random variables, with the property that the series

is almost surely convergent (i.e., the partial sums are almost surely convergent), and let

.

- (i) Show that

is finite. (Hint: argue by contradiction and use the second Borel-Cantelli lemma.)

- (ii) Show that

is finite. (Hint: first use (i) and the Borel-Cantelli lemma to reduce to the case where

almost surely. If

is infinite, use Exercise 14 to show that

converges in distribution to a standard normal distribution, and use this to contradict the almost sure convergence of

.)

- (iii) Show that the series

is convergent. (Hint: reduce as before to the case where

almost surely, and apply the forward direction of the three-series theorem to

.)

— 2. The Fourier-analytic approach to the central limit theorem —

Let us now give the standard Fourier-analytic proof of the central limit theorem. Given any real random variable , we introduce the characteristic function

, defined by the formula

Equivalently, is the Fourier transform of the probability measure

. One should caution that the term “characteristic function” has several other unrelated meanings in mathematics; particularly confusingly, in real analysis “characteristic function” is used to denote what in probability one would call an “indicator function”. Note that no moment hypotheses are required to define the characteristic function, because the random variable

is bounded even when

is not absolutely integrable.

Example 18 The signed Bernoulli distribution, which takes the values

and

with probabilities of

each, has characteristic function

.

Most of the standard random variables in probability have characteristic functions that are quite simple and explicit. For the purposes of proving the central limit theorem, the most important such explicit form of the characteristic function is of the normal distribution:

Exercise 19 Show that the normal distribution

has characteristic function

.

We record the explicit characteristic functions of some other standard distributions:

Exercise 20 Let

, and let

be a Poisson random variable with intensity

, thus

takes values in the non-negative integers with

. Show that

for all

.

Exercise 21 Let

be uniformly distributed in some interval

. Show that

for all non-zero

.

Exercise 22 Let

and

, and let

be a Cauchy random variable with parameters

, which means that

is a real random variable with probability density function

. Show that

for all

.

The characteristic function is clearly bounded in magnitude by , and equals

at the origin. By the dominated convergence theorem,

is continuous in

.

Exercise 23 (Riemann-Lebesgue lemma) Show that if

is a real random variable that has an absolutely integrable probability density function

, then

as

. (Hint: first show the claim when

is a finite linear combination of intervals, then for the general case show that

can be approximated in

norm by such finite linear combinations.) Note from Example 18 that the claim can fail if

does not have a probability density function. (In Fourier analysis, this fact is known as the Riemann-Lebesgue lemma.)

Exercise 24 Show that the characteristic function

of a real random variable

is in fact uniformly continuous on its domain.

Let be a real random variable. If we Taylor expand

and formally interchange the series and expectation, we arrive at the heuristic identity

which thus interprets the characteristic function of a real random variable as a kind of generating function for the moments. One rigorous version of this identity is as follows.

Exercise 25 (Taylor expansion of characteristic function) Let

be a real random variable with finite

moment for some

. Show that

is

times continuously differentiable, with

for all

. Conclude in particular the partial Taylor expansion

where

is a quantity that goes to zero as

, times

.

Exercise 26 Let

be a real random variable, and assume that it is subgaussian in the sense that there exist constants

such that

for all

. (Thus for instance a bounded random variable is subgaussian, as is any gaussian random variable.) Rigorously establish (7) in this case, and show that the series converges locally uniformly in

.

Note that the characteristic function depends only on the distribution of : if

and

are equal in distribution, then

. The converse statement is true also: if

, then

and

are equal in distribution. This follows from a more general (and useful) fact, known as Lévy’s continuity theorem.

Theorem 27 (Lévy continuity theorem, special case) Let

be a sequence of real random variables, and let

be an additional real random variable. Then the following statements are equivalent:

- (i)

converges pointwise to

.

- (ii)

converges in distribution to

.

Proof: The implication of (i) from (ii) is immediate from (6) and Exercise 10(viii).

Now suppose that (i) holds, and we wish to show that (ii) holds. We need to show that

whenever is a continuous, compactly supported function. As in the Lindeberg argument, it suffices to prove this when

is smooth and compactly supported, in particular

is a Schwartz function (infinitely differentiable, with all derivatives rapidly decreasing). But then we have the Fourier inversion formula

where

is Schwartz, and is in particular absolutely integrable (see e.g. these lecture notes of mine). From the Fubini-Tonelli theorem, we thus have

and similarly for . The claim now follows from the Lebesgue dominated convergence theorem.

Remark 28 Setting

for all

, we see in particular the previous claim that

if and only if

,

have the same distribution. It is instructive to use the above proof as a guide to prove this claim directly.

There is one subtlety with the Lévy continuity theorem: it is possible for a sequence of characteristic functions to converge pointwise, but for the limit to not be the characteristic function of any random variable, in which case

will not converge in distribution. For instance, if

, then

converges pointwise to

for any

, but this is clearly not the characteristic function of any random variable (as characteristic functions are continuous). However, this lack of continuity is the only obstruction:

Exercise 29 (Lévy’s continuity theorem, full version) Let

be a sequence of real valued random variables. Suppose that

converges pointwise to a limit

. Show that the following are equivalent:

- (i)

is continuous at

.

- (ii)

is a tight sequence (as in Exercise 10(iii)).

- (iii)

is the characteristic function of a real valued random variable

(possibly after extending the sample space).

- (iv)

converges in distribution to some real valued random variable

(possibly after extending the sample space).

Hint: To get from (ii) to the other conclusions, use Theorem 11 and Theorem 27. To get back to (ii) from (i), use (8) for a suitable Schwartz function

. The other implications are easy once Theorem 27 is in hand.

Remark 30 Lévy’s continuity theorem is very similar in spirit to Weyl’s criterion in equidistribution theory.

Exercise 31 (Esséen concentration inequality) Let

be a random variable taking values in

. Then for any

,

, show that

for some constant

depending only on

. (Hint: Use (8) for a suitable Schwartz function

.) The left-hand side of (9) (as well as higher dimensional analogues of this quantity) is known as the small ball probability of

at radius

.

In Fourier analysis, we learn that the Fourier transform is a particularly well-suited tool for studying convolutions. The probability theory analogue of this fact is that characteristic functions are a particularly well-suited tool for studying sums of independent random variables. More precisely, we have

Exercise 32 (Fourier identities) Let

be independent real random variables. Then

for all

. Also, for any scalar

, one has

and more generally, for any linear transformation

, one has

Remark 33 Note that this identity (10), combined with Exercise 19 and Remark 28, gives a quick alternate proof of Lemma 12.

In particular, we have the simple relationship

that describes the characteristic function of in terms of that of

.

We now have enough machinery to give a quick proof of the central limit theorem:

Proof: (Fourier proof of Theorem 8) We may normalise to have mean zero and variance

. By Exercise 25, we thus have

for sufficiently small , or equivalently

for sufficiently small . Applying (11), we conclude that

as for any fixed

. But by Exercise 19,

is the characteristic function of the normal distribution

. The claim now follows from the Lévy continuity theorem.

The above machinery extends without difficulty to vector-valued random variables taking values in

. The analogue of the characteristic function is then the function

defined by

We leave the routine extension of the above results and proofs to the higher dimensional case to the reader. Most interesting is what happens to the central limit theorem:

Exercise 34 (Vector-valued central limit theorem) Let

be a random variable taking values in

with finite second moment. Define the covariance matrix

to be the

matrix

whose

entry is the covariance

.

- Show that the covariance matrix is positive semi-definite real symmetric.

- Conversely, given any positive definite real symmetric

matrix

and

, show that the multivariate normal distribution

, given by the absolutely continuous measure

has mean

and covariance matrix

, and has a characteristic function given by

How would one define the normal distribution

if

degenerated to be merely positive semi-definite instead of positive definite?

- If

is the sum of

iid copies of

, show that

converges in distribution to

. (For this exercise, you may assume without proof that the Lévy continuity theorem extends to

.)

Exercise 35 (Complex central limit theorem) Let

be a complex random variable of mean

, whose real and imaginary parts have variance

and covariance

. Let

be iid copies of

. Show that as

, the normalised sums

converge in distribution to the standard complex gaussian

, defined as the measure

on

with

for Borel

, where

is Lebesgue measure on

(identified with

in the usual fashion).

Exercise 36 Use characteristic functions and the truncation argument to give an alternate proof of the Lindeberg central limit theorem (Theorem 14).

A more sophisticated version of the Fourier-analytic method gives a more quantitative form of the central limit theorem, namely the Berry-Esséen theorem.

Theorem 37 (Berry-Esséen theorem) Let

have mean zero and unit variance. Let

, where

are iid copies of

. Then we have

uniformly for all

, where

has the distribution of

, and the implied constant is absolute.

Proof: (Optional) Write ; our task is to show that

for all . We may of course assume that

, as the claim is trivial otherwise. (In particular,

has finite third moment.)

Let be a small absolute constant to be chosen later. Let

be an non-negative Schwartz function with total mass

whose Fourier transform is supported in

; such an

can be constructed by taking the inverse Fourier transform of a smooth function supported on

and equal to one at the origin, and then multiplying that transform by its complex conjugate to make it non-negative.

Let be the smoothed out version of

, defined as

Observe that is decreasing from

to

. As

is rapidly decreasing and has mean one, we also have the bound

(say) for any , where subscript indicates that the implied constant depends on

.

We claim that it suffices to show that

for every , where the subscript means that the implied constant depends on

. Indeed, suppose that (15) held. Replacing

by

and

for some large absolute constant

and subtracting, we have

for any . From (14) we see that the function

is bounded by

, and hence by the bounded probability density of

Also, is non-negative, and for

large enough, it is bounded from below by (say)

on

. We conclude (after choosing

appropriately) that

for all real . This implies that

as can be seen by covering the real line by intervals and applying (16) to each such interval. From (14) we conclude that

A similar argument gives

and (13) then follows from (15).

It remains to establish (15). We write

(with the expression in the limit being uniformly bounded) and

to conclude (after applying Fubini’s theorem) that

using the compact support of . Hence

By the fundamental theorem of calculus we have . This factor of

cancels a similar factor on the denominator to make the expression inside the limit dominated by an absolutely integrable random variable. Thus by the dominated convergence theorem

and so it suffices to show that

uniformly in . Applying the triangle inequality and the compact support of

, it suffices to show that

From Taylor expansion we have

for any ; taking expectations and using the definition of

we have

and in particular

if and

is small enough. Applying (11), we conclude that

if . Meanwhile, from Exercise 19 we have

. Elementary calculus then gives us

(say) if is small enough. Inserting this bound into (17) we obtain the claim.

Exercise 38 Show that the error terms in Theorem 37 are sharp (up to constants) when

is a signed Bernoulli random variable, or more precisely when

takes values in

with probability

for each.

Exercise 39 Let

be a sequence of real random variables which converge in distribution to a real random variable

, and let

be a sequence of real random variables which converge in distribution to a real random variable

. Suppose that, for each

,

and

are independent, and suppose also that

and

are independent. Show that

converges in distribution to

. (Hint: use the Lévy continuity theorem.)

The following exercise shows that the central limit theorem fails when the variance is infinite.

Exercise 40 Let

be iid copies of an absolutely integrable random variable

of mean zero.

- (i) In this part we assume that

is symmetric, which means that

and

have the same distribution. Show that for any

and

,

(Hint: relate both sides of this inequality to the probability of the event that

and

, using the symmetry of the situation.)

- (ii) If

is symmetric and

converges in distribution to a real random variable

, show that

has finite variance. (Hint: if this is not the case, then

will have arbitrarily large variance as

increases. On the other hand,

can be made arbitrarily small by taking

large enough. For a large threshold

, apply (i) (with

) to obtain a contradiction.

- (iii) Generalise (ii) by removing the hypothesis that

is symmetric. (Hint: apply the symmetrisation trick of replacing

by

, where

is an independent copy of

, and use the previous exercise. One may need to utilise some truncation arguments to show that

has infinite variance whenever

has infinite variance.)

Exercise 41

- (i) If

is a real random variable of mean zero and variance

, and

is a real number, show that

and that

(Hint: first establish the Taylor bounds

and

.)

- (ii) Establish the pointwise inequality

whenever

are complex numbers in the disk

.

- (iii) Suppose that for each

,

are jointly independent real random variables of mean zero and finite variance, obeying the uniform bound

for all

and some

going to zero as

, and also obeying the variance bound

as

for some

. If

, use (i) and (ii) to show that

as

for any given real

.

- (iv) Use (iii) and a truncation argument to give an alternate proof of the Lindeberg central limit theorem (Theorem 14). (Note: one has to address the issue that truncating a random variable may alter its mean slightly.)

— 3. The moment method —

The above Fourier-analytic proof of the central limit theorem is one of the quickest (and slickest) proofs available for this theorem, and is accordingly the “standard” proof given in probability textbooks. However, it relies quite heavily on the Fourier-analytic identities in Exercise 32, which in turn are extremely dependent on both the commutative nature of the situation (as it uses the identity ) and on the independence of the situation (as it uses identities of the form

). As one or both of these factors can be absent when trying to generalise this theorem, it is also important to look for non-Fourier based methods to prove results such as the central limit theorem. These methods often lead to proofs that are lengthier and more technical than the Fourier proofs, but also tend to be more robust.

The most elementary (but still remarkably effective) method available in this regard is the moment method, which we have already used in previous notes. In principle, this method is equivalent to the Fourier method, through the identity (7); but in practice, the moment method proofs tend to look somewhat different than the Fourier-analytic ones, and it is often more apparent how to modify them to non-independent or non-commutative settings.

We first need an analogue of the Lévy continuity theorem. Here we encounter a technical issue: whereas the Fourier phases were bounded, the moment functions

become unbounded at infinity. However, one can deal with this issue as long as one has sufficient decay:

Exercise 42 (Subgaussian random variables) Let

be a real random variable. Show that the following statements are equivalent:

- (i) There exist

such that

for all

.

- (ii) There exist

such that

for all

.

- (iii) There exist

such that

for all

.

Furthermore, show that if (i) holds for some

, then (ii) holds for

depending only on

, and similarly for any of the other implications. Variables obeying (i), (ii), or (iii) are called subgaussian. The function

is known as the moment generating function of

; it is of course closely related to the characteristic function of

.

Exercise 43 Use the truncation method to show that in order to prove the central limit theorem (Theorem 8), it suffices to do so in the case when the underlying random variable

is bounded (and in particular subgaussian).

Once we restrict to the subgaussian case, we have an analogue of the Lévy continuity theorem:

Theorem 44 (Moment continuity theorem) Let

be a sequence of real random variables, and let

be a subgaussian random variable. Suppose that for every

,

converges pointwise to

. Then

converges in distribution to

.

Proof: Let , then by the preceding exercise we have

for some independent of

. In particular,

when is sufficiently large depending on

. From Taylor’s theorem with remainder (and Stirling’s formula (1)) we conclude

uniformly in , for

sufficiently large. Similarly for

. Taking limits using (i) we see that

Then letting , keeping

fixed, we see that

converges pointwise to

for each

, and the claim now follows from the Lévy continuity theorem.

We remark that in place of Stirling’s formula, one can use the cruder lower bound , which is immediate from the observation that

occurs in the Taylor expansion of

.

Remark 45 One corollary of Theorem 44 is that the distribution of a subgaussian random variable is uniquely determined by its moments (actually, this could already be deduced from Exercise 26 and Remark 28). The situation can fail for distributions with slower tails, for much the same reason that a smooth function is not determined by its derivatives at one point if that function is not analytic.

The Fourier inversion formula provides an easy way to recover the distribution from the characteristic function. Recovering a distribution from its moments is more difficult, and sometimes requires tools such as analytic continuation; this problem is known as the inverse moment problem and will not be discussed here.

Exercise 46 (Converse direction of moment continuity theorem) Let

be a sequence of uniformly subgaussian random variables (thus there exist

such that

for all

and all

), and suppose

converges in distribution to a limit

. Show that for any

,

converges pointwise to

.

We now give the moment method proof of the central limit theorem. As discussed above we may assume without loss of generality that is bounded (and in particular subgaussian); we may also normalise

to have mean zero and unit variance. By Theorem 44, it suffices to show that

for all , where

is a standard gaussian variable.

The moments were already computed in Exercise 37 of Notes 1. So now we need to compute

. Using linearity of expectation, we can expand this as

To understand this expression, let us first look at some small values of .

- For

, this expression is trivially

.

- For

, this expression is trivially

, thanks to the mean zero hypothesis on

.

- For

, we can split this expression into the diagonal and off-diagonal components:

Each summand in the first sum is

, as

has unit variance. Each summand in the second sum is

, as the

have mean zero and are independent. So the second moment

is

.

- For

, we have a similar expansion

The summands in the latter two sums vanish because of the (joint) independence and mean zero hypotheses. The summands in the first sum need not vanish, but are

, so the first term is

, which is asymptotically negligible, so the third moment

goes to

.

- For

, the expansion becomes quite complicated:

Again, most terms vanish, except for the first sum, which is

and is asymptotically negligible, and the sum

, which by the independence and unit variance assumptions works out to

. Thus the fourth moment

goes to

(as it should).

Now we tackle the general case. Ordering the indices as

for some

, with each

occuring with multiplicity

and using elementary enumerative combinatorics, we see that

is the sum of all terms of the form

where ,

are positive integers adding up to

, and

is the multinomial coefficient

The total number of such terms depends only on (in fact, it is

(exercise!), though we will not need this fact).

As we already saw from the small examples, most of the terms vanish, and many of the other terms are negligible in the limit

. Indeed, if any of the

are equal to

, then every summand in (18) vanishes, by joint independence and the mean zero hypothesis. Thus, we may restrict attention to those expressions (18) for which all the

are at least

. Since the

sum up to

, we conclude that

is at most

.

On the other hand, the total number of summands in (18) is clearly at most (in fact it is

), and the summands are bounded (for fixed

) since

is bounded. Thus, if

is strictly less than

, then the expression in (18) is

and goes to zero as

. So, asymptotically, the only terms (18) which are still relevant are those for which

is equal to

. This already shows that

goes to zero when

is odd. When

is even, the only surviving term in the limit is now when

and

. But then by independence and unit variance, the expectation in (18) is

, and so this term is equal to

and the main term is happily equal to the moment as computed in Exercise 37 of Notes 1. (One could also appeal to Lemma 12 here, specialising to the case when

is normally distributed, to explain this coincidence.) This concludes the proof of the central limit theorem.

Exercise 47 (Chernoff bound) Let

be iid copies of a real random variable

of mean zero and unit variance, which is subgaussian in the sense of Exercise 42. Write

.

- (i) Show that there exist

such that

for all

. Conclude that

for all

. (Hint: the first claim follows directly from Exercise 42 when

; for

, use the Taylor approximation

.)

- (ii) Conclude the Chernoff bound

for some

, all

, and all

.

Exercise 48 (Erdös-Kac theorem) For any natural number

, let

be a natural number drawn uniformly at random from the natural numbers

, and let

denote the number of distinct prime factors of

.

- (i) Show that for any

, one has

as

if

is odd, and

as

if

is even. (Hint: adapt the arguments in Exercise 16 of Notes 3, estimating

by

, using Mertens’ theorem and induction on

to deal with lower order errors, and treating the random variables

as being approximately independent and approximately of mean zero.)

- (ii) Establish the Erdös-Kac theorem

as

for any fixed

.

Informally, the Erdös-Kac theorem asserts that

behaves like

for “random”

. Note that this refines the Hardy-Ramanujan theorem (Exercise 16 of Notes 3).

72 comments

Comments feed for this article

2 November, 2015 at 7:56 pm

Anonymous

may want to add “275A – probability theory” in the tags

[Added, thanks – T.]

3 November, 2015 at 5:46 am

Anonymous

In theorem 36, the assumption is not really needed (since otherwise (11) holds trivially!)

is not really needed (since otherwise (11) holds trivially!)

[Assumption removed, thanks – T.]

3 November, 2015 at 11:07 am

Anonymous

You should use instead of

instead of  and $\cdots$, resp.

and $\cdots$, resp.

3 November, 2015 at 7:21 pm

Anonymous

In exercise 13(ii), “ ” is in fact “

” is in fact “ “, and the expectation should be dependent on the index

“, and the expectation should be dependent on the index  .

.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

4 November, 2015 at 9:09 am

Anonymous

According to the Wikipedia articles on the CLT and the Berry-Esseen theorem:

1. The term “central limit theorem” (in German) was first used by Polya (in 1920) where the word “central” is due to its central importance in probability theory. The later interpretation of “central” in the sense that the CLT describes the behaviour of the distribution near its center is (according to Le Cam) due to the French school on probability.

2. The best implied constant in the error term in 11, is lower-bounded by (Esseen, 1956) and upper-bounded by

(Esseen, 1956) and upper-bounded by  (Shevtsova, 2011).

(Shevtsova, 2011).

4 November, 2015 at 9:46 am

Anonymous

In the proof of Theorem 26 you briefly switch to $R^d$

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

4 November, 2015 at 9:57 am

Anonymous

A useful lemma is that if $X_n$ converge in distribution they can be coupled to converge almost surely. This is also an instructive alternate approach to the second direction in Proposition 4.

[This was the intention of Exercise 10(iv), though I had previously only asked for convergence in probability, and have now strengthened the conclusion. -T.]

4 November, 2015 at 11:18 am

Anonymous

It seems that exercise 10(vi) generalizes Slutsky’s theorem (which deals with a degenerate(!) limit ), but in the Wikipedia article on Slutsky’s theorem (according to the second note) it is claimed that the requirement that

), but in the Wikipedia article on Slutsky’s theorem (according to the second note) it is claimed that the requirement that  is degenerate(!) is important (the theorem is not (!) valid in general for a non-degenerate limit

is degenerate(!) is important (the theorem is not (!) valid in general for a non-degenerate limit  ) – is this claim true?

) – is this claim true?

[Oops, this was an error – the exercise has now been corrected. -T.]

5 November, 2015 at 6:52 am

Anonymous

Exercise 9, definition of distribution at the beginning has typo.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

5 November, 2015 at 9:45 am

John Mangual

The Lindberg approach is related to the “renormalization group approach”, as I learned from Yakov Sinai.

However, I couldn’t not reconcile the discussions of RG in hep-th and the discussion in the probability textbook.

5 November, 2015 at 12:21 pm

Joop de Maat

A typo (“equvialence” before Remark 3) and a question: How exactly are the two notions of distributions from Remark 3 similar ? You only indicated in what the where different, not in what they are alike.

5 November, 2015 at 12:54 pm

Terence Tao

Thanks for the correction! The similarity is both notions of convergence require testing against “nice” functions (continuous compactly supported functions in the case of convergence in distribution, and smooth compactly supported functions in the case of convergence in the sense of distributions). In particular, it is true that a sequence of random variables converge in distribution to a random variable

converge in distribution to a random variable  if and only if the probability measures

if and only if the probability measures  converge in the sense of distributions to

converge in the sense of distributions to  . (But once one leaves the setting of probability measures, one can have more exotic distributions as the distributional limit, e.g. derivatives of delta functions.)

. (But once one leaves the setting of probability measures, one can have more exotic distributions as the distributional limit, e.g. derivatives of delta functions.)

14 November, 2015 at 11:59 am

Venky

In the Lindberg approach, I was trying to see where the Gaussian nature of the pdf of Y_i is important other than (3). Can one say that an implication of CLT is that the Gaussian pdf is the only pdf that preserves its functional form over countable addition of independent variables? Great notes, thanks.

14 November, 2015 at 12:20 pm

Terence Tao

Yes, the gaussian is the only finite-variance stable law, and the Lindeberg argument explains why there can be at most one such law. (But there are other stable laws in the infinite variance case, which lie outside of the reach of the CLT: for instance, the Cauchy distribution is also stable.)

14 November, 2015 at 4:35 pm

Anonymous

I have a question on the Example 5, we have known that Xn converges to X in distribution, where Xn is uniform distributed on {1/n, 2/n, …, n/n} and X is uniform[0,1]. How can we check that if Xn converges to X in prob?

14 November, 2015 at 6:49 pm

Terence Tao

This is not possible from the information given, because we do not know the joint distribution of , only the individual distributions of

, only the individual distributions of  and

and  ; the joint distribution is irrelevant for the question of whether there is convergence in distribution, but is very relevant for convergence in probability For instance,

; the joint distribution is irrelevant for the question of whether there is convergence in distribution, but is very relevant for convergence in probability For instance,  could be

could be  rounded up to the next multiple of

rounded up to the next multiple of  , in which case

, in which case  converges to

converges to  in probability (and almost surely). Or,

in probability (and almost surely). Or,  could be independent of

could be independent of  , in which case it will not converge in probability or almost surely to

, in which case it will not converge in probability or almost surely to  .

.

18 November, 2015 at 3:42 pm

Terence Tao

There appears to be a strange issue with one of the wordpress LaTeX renderers right now, as some simple expressions such as are not rendering properly while others such as

are not rendering properly while others such as  are fine. For those in the class following the notes online, a temporary workaround is to hover one’s mouse over the improperly rendered images to see the uncompiled LaTeX. I do not seem to be able to fix the issue on my end, but I’m hoping that the problem will resolve itself shortly (at which point I will remove this comment).

are fine. For those in the class following the notes online, a temporary workaround is to hover one’s mouse over the improperly rendered images to see the uncompiled LaTeX. I do not seem to be able to fix the issue on my end, but I’m hoping that the problem will resolve itself shortly (at which point I will remove this comment).

19 November, 2015 at 8:25 am

Terence Tao

OK, the problem seems to be that as of about 24 hours ago, wordpress has become unable to render any latex fragment that it has not previously rendered, presumably due to the machine that does all the new renderings being somehow offline. I’d be interested to see if other wordpress.com sites are having the same issue, in which case it would make sense to report it. In the meantime, I’ve rolled back these notes to an earlier version for now to avoid the rendering errors. [Update: it now appears that the issue is affecting all wordpress.com blogs, and has been reported. -T.]

19 November, 2015 at 11:38 am

ianmarqz

I have the same problem of well rendering : ( sample: https://juanmarqz.wordpress.com/about/sum-of-reciprocals/

19 November, 2015 at 2:51 pm

275A, Notes 5: Variants of the central limit theorem | What's new

[…] the previous set of notes we established the central limit theorem, which we formulate here as […]

23 November, 2015 at 7:44 pm

Dillon

The characteristic function for a uniform distribution on an interval (Exercise 21) is missing an in the denominator. Also some of the preceding exercises still say

in the denominator. Also some of the preceding exercises still say  for the characteristic function where

for the characteristic function where  would be more consistent.

would be more consistent.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

24 November, 2015 at 6:48 pm

Anonymous

In exercise 10 (vii), should it be liminf EG(X_n)>= EG(X)?

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

30 November, 2015 at 3:48 am

Anonymous

‘non-engative’ should be ‘non-negative’ (search and replace time)

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

30 November, 2015 at 4:02 am

Anonymous

‘Levi continuity theorem’ should be ‘Lévy continuity theorem’ (search and replace again)

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

2 December, 2015 at 3:24 am

jura05

thank you for these lectures!

and apply it to X=S_n/sqrt{n}-a, Y=N-a

and apply it to X=S_n/sqrt{n}-a, Y=N-a

some typos:

– formula after (14) – missing term O(.)

– before (15): instead of “below by 1/2 on [0,eps]” should be “below by 1/2 on [a,a+eps]”

– proof of (14) goes for the special case a=0; although there is no difference.. maybe it is convenient to write a general bound

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

30 May, 2016 at 12:56 am

Anonymous

Thanks for the great notes. Small typos:

1. inequality (2) and the following equation are missing a square in the $(x-x_1)^2$ term.

2. Closed bracket missing in Ex 17 (ii)

3. Ex 17 (iii), the indicator function doesn’t appear correctly.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

30 May, 2016 at 7:56 am

Anonymous

What is known about the convergence rate in Erdos-Kac theorem?

30 May, 2016 at 10:49 am

Terence Tao

I think this paper by Harper represents the current state of the art: http://www.ams.org/mathscinet-getitem?mr=2507311

2 October, 2016 at 6:53 am

Anonymous

In Exercise 14, for each ,

,  are jointly independent. What do you mean by “We do not require the random variables

are jointly independent. What do you mean by “We do not require the random variables  to be jointly independent in

to be jointly independent in  “? Would you illustrate by giving an example that what could be dependent here?

“? Would you illustrate by giving an example that what could be dependent here?

[For instance, we do not require the tuple to be independent of

to be independent of  . -T.]

. -T.]

4 October, 2016 at 5:55 am

Anonymous

In Exercise 25, can one avoid calculating the -th derivative of

-th derivative of  by just directly integrating the Taylor expansion of

by just directly integrating the Taylor expansion of  ?

?

[This should work also, as long as one is careful with estimating error terms – T.]

4 October, 2016 at 6:17 am

Anonymous

For Exercise 19, all the textbooks I have seen use the contour integrals. Can one do it with other methods than the one in complex analysis?

[One such method begins by observing that the pdf of the normal distribution obeys an ODE which then translates to an ODE for the characteristic function (cf. Stein’s method). -T]

4 October, 2016 at 6:23 am

Anonymous

In the Fourier proof of Theorem 8, would you elaborate the “equivalently” part? Is the parenthesis a typo there?

[We are using the Taylor approximation for small

for small  (specifically,

(specifically,  ). -T.]

). -T.]

4 October, 2016 at 7:09 pm

Anonymous

By direct substitution, I got

For fixed $t$, when taking the limit, how do you get rid of the little o term?

4 October, 2016 at 9:26 pm

Terence Tao

The asymptotic notation here is with respect to the limit

here is with respect to the limit  , rather than

, rather than  ,so the

,so the  term goes to zero in the limit when

term goes to zero in the limit when  is fixed and

is fixed and  goes to infinity. (By the way, I corrected a typo in my previous answer, in which I had omitted a factor of

goes to infinity. (By the way, I corrected a typo in my previous answer, in which I had omitted a factor of  in the choice of

in the choice of  .)

.)

5 October, 2016 at 1:00 pm

Anonymous

In Exercise 14, what is the intuition of the Lindeberg condition?

Why would one expect such a condition implies the desired result?

6 October, 2016 at 11:40 am

Terence Tao

The central limit theorem can fail if there is a significant probability that one of the summands is so large that it is comparable to the total standard deviation

is so large that it is comparable to the total standard deviation  . The Lindeberg condition is basically an assertion that these sort of outlier events are vanishingly rare (and their contribution to the sum has vanishingly small variance) in the limit

. The Lindeberg condition is basically an assertion that these sort of outlier events are vanishingly rare (and their contribution to the sum has vanishingly small variance) in the limit  .

.

6 October, 2016 at 6:03 pm

Anonymous

I saw Billingsley in his Probability and Measure proves Remark 28 by proving the inversion formula:

If the probability measure has characteristic function

has characteristic function  and $\mu\{a\}=\mu\{b\}=0$, then

and $\mu\{a\}=\mu\{b\}=0$, then

![\displaystyle \mu(a,b]=\lim_{T\to\infty}\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-T}^T\frac{e^{-ita}-e^{-itb}}{it}\ dt.](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle+%5Cmu%28a%2Cb%5D%3D%5Clim_%7BT%5Cto%5Cinfty%7D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%5Cpi%7D%5Cint_%7B-T%7D%5ET%5Cfrac%7Be%5E%7B-ita%7D-e%5E%7B-itb%7D%7D%7Bit%7D%5C+dt.+&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002)

This approach looks rather different from the one in the proof of Theorem 27, which uses the Schwartz functions and is much shorter. What makes the Schwartz function-approach faster and is it hinted somewhere that these two approaches are essentially the same?

8 October, 2016 at 4:58 am

Anonymous

Ah, the inversion formula should be

![\displaystyle \mu(a,b]=\lim_{T\to\infty}\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-T}^T\frac{e^{-ita}-e^{-itb}}{it}\varphi(t) dt.](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle+%5Cmu%28a%2Cb%5D%3D%5Clim_%7BT%5Cto%5Cinfty%7D%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%5Cpi%7D%5Cint_%7B-T%7D%5ET%5Cfrac%7Be%5E%7B-ita%7D-e%5E%7B-itb%7D%7D%7Bit%7D%5Cvarphi%28t%29+dt.+&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002)

Actually, the proof of the inversion formula is not that long. The key step is just exchanging the integral using Fubini and taking the limit. Still it looks rather different from the Schwartz-function-approach.

8 October, 2016 at 8:40 am

Terence Tao

Basically the difference lies in the use of the smoothing sums technique: replacing a rough cutoff such as![1_{[a,b]}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=1_%7B%5Ba%2Cb%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) with a smoother cutoff in order to enjoy better decay of the Fourier transform. The price one pays for this is that the formulae become a little less explicit, possibly leading to worse quantitative bounds in some cases, but in many applications this sort of loss is acceptable.

with a smoother cutoff in order to enjoy better decay of the Fourier transform. The price one pays for this is that the formulae become a little less explicit, possibly leading to worse quantitative bounds in some cases, but in many applications this sort of loss is acceptable.

12 October, 2016 at 5:57 pm

Anonymous

In theorem 11, can we replace random variables with random vectors?

[Yes; see for instance the linked exercise. -T.]

13 October, 2016 at 6:55 pm

Anonymous

Also for Proposition 4 and Exercise 7 one can have random vectors instead? I’m wondering if i missed reading some of the notes about the random vector part or it is just trivial generalization.

14 October, 2016 at 6:37 pm

Terence Tao

If one deletes (ii) then the remaining claims are equivalent in the vector-valued case. But it is not clear to me whether there is an analogue for (ii) in the vector-valued case (one has to define the cumulative distribution function properly, and specify exactly what a “point of continuity” would mean for that function); the proof given is restricted to the scalar case.

14 October, 2016 at 6:57 pm

Anonymous

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cumulative_distribution_function#Multivariate_case

13 October, 2016 at 6:26 pm

Anonymous

In Exercise 7, do you have a hint for (v) —>(i)? I don’t have any idea why the boundary of would have anything to do with continuity of a function.

would have anything to do with continuity of a function.

[Consider sets of the form

of the form ![E = (-\infty,t]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=E+%3D+%28-%5Cinfty%2Ct%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) . -T.]

. -T.]

13 October, 2016 at 6:52 pm

Anonymous

In the proof of Proposition 4, is a typo? Likewise for several others?

a typo? Likewise for several others?

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

22 May, 2017 at 5:55 pm

Quantitative continuity estimates | What's new

[…] starting point for the Lindeberg exchange method in probability theory, discussed for instance in this previous post. The identity in (ii) can also be used in the Lindeberg exchange method; the terms in the […]

25 June, 2017 at 4:51 pm

Discotech

In exercise 35, should the exponent have a $\pi$? I think maybe it should not. Unless I’m misunderstanding the meaning of the Lebesgue integral over the complex plane, the measure defined isn’t normalized to 1.

In the hint on exercise 40, do you mean to refer to the probability $P( X_1 1_{|X_1|>M} + \dots + X_n 1_{|X_d|>M} \geq 0)$ (greater than signs instead of less than signs)?

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

26 October, 2018 at 4:05 am

Anonymous

In Slutsky’s theorem, can one relax the condition regarding the convergence of to be convergence in distribution?

to be convergence in distribution?

27 October, 2018 at 9:03 am

Terence Tao

When the limit is deterministic, convergence in distribution is the same as convergence in probability.

is deterministic, convergence in distribution is the same as convergence in probability.

20 February, 2019 at 2:46 pm

haonanz

Hello Prof. Tao, I have a question regard Exercise 7 prove ii) => v). I am thinking if I could use sigma algebra like proof. I believe the difficulty comes from the fact we have only convergence at continuity point. If we assume it’s true for all t, then I think I can show that the set of E satisfy this property is closed under countable union and countable closure), then use the fact Borel sets are the smallest sigma algebra generated by the half-intervals to complete the proof. I wonder the fact we know those discontinuity is at most countably many points can somehow be used to show this generated sigma algebra still contains the half-intervals thus the borel set.

21 February, 2019 at 8:48 am

Terence Tao

I’m not sure a sigma algebra approach will be easy to execute, because the set of Borel sets with

with  of measure zero is not closed under countable union or countable intersection. (The strategy I had in mind instead is to approximate

of measure zero is not closed under countable union or countable intersection. (The strategy I had in mind instead is to approximate  by its interior and its exterior and use (iii), (iv).)

by its interior and its exterior and use (iii), (iv).)

23 February, 2019 at 7:06 am

haonanz

A follow up question regard proving i)=>iii), I can prove the claim for the compact case using upper approximation of a CTS and compact supported function. Do you mind providing hint on how can I extend this to the closed case? Thanks again!

23 February, 2019 at 8:12 am

Terence Tao

Show that for large , the probability

, the probability  is close to 1, then show that the probability

is close to 1, then show that the probability  is close to 1 for large

is close to 1 for large  , thus the probability

, thus the probability  is small.

is small.

6 November, 2019 at 3:54 am

anonymous

There should be a $k_n$ instead of $n$ in point (ii) of exercise 14.

[Corrected, thanks – T]

18 April, 2020 at 2:07 pm

Anonymous

Let be iid Bernoulli(

be iid Bernoulli( ) random variables, that is,

) random variables, that is,  and

and  .

.

Let

where .

.

Show that and determine

and determine  .

.

How can we prove this by using some elementary tools?

24 December, 2020 at 3:43 am

Aditya Guha Roy

You may try to solve it using the central limit theorem and Slutsky’s theorem. I have not done this very exercise, but it seems that this can be done by using these tools. Try it and let us know here.

1 January, 2021 at 8:37 pm

N is a number

Yes that would work. I just checked it.

23 December, 2020 at 4:59 am

Aditya Guha Roy

On line number 22 of these notes, you have written about applying Paley Zygmund inequality to get the mentioned lower bound.

I think there is a typo in labelling it as Exercise 42 of Notes 1 ; it should be Exercise 44 of Notes 1.

[Corrected, thanks – T.]

1 January, 2021 at 6:01 am

N is a number

In Exercise 19, we see that from the definition of characteristic function it suffices to show that the result holds when and

and  Now that calls for showing

Now that calls for showing ![\mathbf{E} [ e^{i tX} ] = e^{-t^2 / 2}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbf%7BE%7D+%5B+e%5E%7Bi+tX%7D+%5D+%3D+e%5E%7B-t%5E2+%2F+2%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) for all complex numbers

for all complex numbers  Now rewriting the LHS as an integral one has a holomorphic function on the LHS and the RHS is also a holomorphic function. Now, one can prove this identity for the case when

Now rewriting the LHS as an integral one has a holomorphic function on the LHS and the RHS is also a holomorphic function. Now, one can prove this identity for the case when  is purely imaginary so that

is purely imaginary so that  is purely real by a direct evaluation of the integral which appears on the LHS.

is purely real by a direct evaluation of the integral which appears on the LHS.

Now, using the fact that non-trivial holomorphic maps have isolated zeroes, and identifying that the holomorphic map LHS – RHS is zero identically on the imaginary axis, one concludes that the identity holds for all complex numbers

Is that correct ?

[Sure, this works. One can also compute the integral for arbitrary by completing the square and contour shifting instead of relying on analytic continuation. -T]

by completing the square and contour shifting instead of relying on analytic continuation. -T]

1 January, 2021 at 9:01 pm

Aditya Guha Roy

I think to show that![\mathbf{E} [ e^{it X} ]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbf%7BE%7D+%5B+e%5E%7Bit+X%7D+%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=545454&s=0&c=20201002) is holomorphic over

is holomorphic over  , an easy way is to notice that it is the derivative of the holomorphic map